Poetry Review: Marcia Karp’s “If By Song” — Verse Passionate and Unruly

By Merrill Kaitz

This is a volume filled with complex pleasures and pains, assembled with purpose.

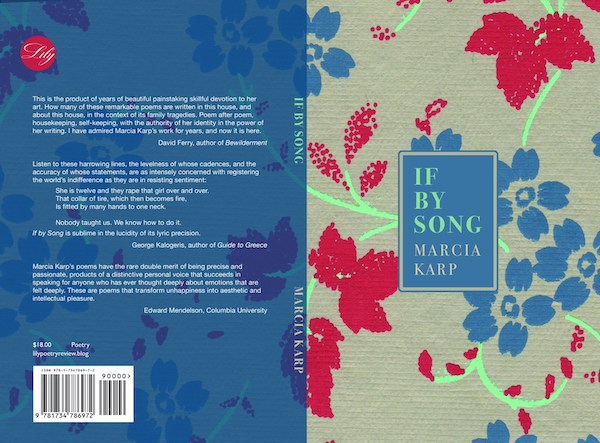

If By Song by Marcia Karp. Lily Poetry Review Books, 117 pp., paperback, $18.

If By Song, Marcia Karp’s fine debut collection, ranges wider and more deeply than most. It seems to contain a full life, or at least more than half of one, teeming with loves enjoyed, lost, rekindled, re-lost, newfound. Travails of love are inextricably bound with portraits of a poet (or her personae) seeking both a personal and a poetic voice, identity, and truth. Often, there are notes of bitterness, anger, and despair. But there’s also hope and joy, in a full and mature voice:

How have you come, now I find

upon deep sleep’s long leaving,

to lie in deep hum in my arms?

Fine wit and sweet lyricism intertwine in Karp’s lines (at times reminding me of John Donne). There are tones of Sappho and Catullus, which Karp confirms by providing a few translations of (or homages to) each in one of the book’s final sections. Frequently there are puns and free association, giving the feeling of the mind’s own expansive motion, reminiscent of the prose of Virginia Woolf or James Joyce. Clearly, this is no commonplace pile of verses. Rather, it’s a volume of complex pleasures and pains, assembled with purpose.

Let’s start with two poems, the first in the book, “If Asked, She Says Only,” and the title poem (which comes some 80 pages later), another if, “If By Song, Words.”

The first begins,

If asked she says only

“I am no one.”

This could be an answer, or an echo, to Emily Dickinson’s question: “I’m nobody. Who are you?” But a few lines later, there seem to be more people involved:

She says all the eyes

have closed to her;

Without them she is no one

to herself.

The eyes may belong to others, maybe a multitude of others. But one suspects that they are also iterations of the first person singular, the “I,” the “I’s.”

She knows who she is

and can’t bear it–

Then, after eight two-line stanzas, the final six stanzas provide a sonnet-like reversal of focus. We are told that her own eyes “whirl in their tearpools” and “the other/ feels lost and uncourted,” and she “calls herself / only some no one,”

Blinding

hundreds of eyes

Which had recognized

someone long since in need of some home.

Such is the introductory story in this collection. We meet a voice that is, by turns, or simultaneously, witty and lyrical, content or sad, found and lost and found again, uncertain and surviving. She may or may not be “no one,” but she constantly finds herself in a sort of crowd, being watched by one or many observers, who are a suitor, a lover, or an enemy, or all of these at once.

“If By Song, Words” is a long poem (123 lines), the longest in the book, placed toward its end. It’s a climax of sorts, though it’s followed by two more sections, which include several riddles, as well as poems, translations, imitations, inspired by the most passionate and unruly of the classical poets, Sappho and Catullus. “If By Song, Words,” however, is a highly personal meditation and recollection of early childhood, a portrait and a cry about how a life can be nurtured, smothered, silenced, by love — whether by too much love, too little love, faulty love.

Though it is many-faceted, the poem’s story and theme remains a poet’s growth, from birth to finding her own words and identity and truth. It begins with two lines in italics:

I have no words.

I meant to have.

This could be a young poet, searching — or it could be a child learning to talk. The poet thinks: “Once I thought I thought great thoughts.” But it might be the child saying, with the pun of “I” and “eye” returning from the earlier poem:

An eye is not enough

An eye that keeps its pictures straight

An eye that names its colors

We see the child held aloft by her father (Held high above,/ in daddy’s arms), her mother present too, watching. There’s love: “Her world had rippled with love.” But there’s definitely a problem. Is it too much love, love that is too controlling, or parents competing for the child’s love? “Riven” seems a key word:

Riven with love

She was so perfectly each of them —

and so “she had an I for everyone.” Maybe she has too much of Keats’s “negative capability,” the power, or maybe compulsion, to feel with everyone.

Obliteration; a kiss, a drowning

Into self. But everything was.

The poem is made of uneven stanzas, seeming to leap forward, pushed and pulled by sound, free association, and punning. Fragments of nursery rhyme and song are as important as ideas. But they are rich and resonant fragments:

Father Time sent Mother Tongue

To fetch a pail of water

There is danger here, danger of losing her self and her voice completely: “Without words she would propagate muteness,” and later, “They’d ridden on her tongue, Interfered with its calving...” and, “My tongue! it was flayed into floundering strips. “they wanted me dumb,” she sings.

But the narrator, whether child or poet, finds a way. In the song about being sent to fetch a pail of water, she finds it in some lovely lines:

So she fetched the water’s wet

The water’s face

The deepy depth

So she fetched the water’s voice…

And there is a triumphant final stanza, concluding:

The anchor is weighed. Away!)

And then she sings: And then she sings…

It’s a strong poem, worthy to give the book its name.

Throughout If By Song, time and again Karp dazzles with her emotion, wit, and insight, all pulled together. Sometimes her diction, in semi-Shakespearean sonnets, sounds almost Shakespearean (yet a line of pentameter may have two left feet):

If I a rosebud, lush plush red red, am,

You, a fusty muffled ointment-daubed worm, are.

Or Karp gives us a memorable, complex proverb (within a poem still more complex):

And underneath the tongue there is a mind

that has no words. It’s there that language is.

And then, for one more example out of so many, there are lines so deep and clear they could be a mountain pool, or the centerpiece of a philosophy, and yet they are only the scene-setting of a short poem:

She’d been saying it so long…

that every person was as surely the world

as every other person was.

It’s not nature poetry that If By Song gives us; Karp is far from the world of Mary Oliver. This poet powerfully articulates all the joy and mess of love and being human.

Merrill Kaitz published the poetry magazine Zeugma, studied with Anne Sexton, Lucie Brock-Broido, and Monroe Engel, and was once 12th-rated Scrabble player in North America.

Congratulations , marcia. Where to purchase book??

Here is the link.