Book Review: “Up to Heaven and Down to Hell” — The High Price of Fracking

By Ed Meek

This is an excellent deep dive into the ways fracking mirrors the many problems we face as we try to change the way we think about energy, individual choice, and climate change.

Up to Heaven and Down to Hell: Fracking, Freedom, and Community in an American Town by Colin Jerolmack. Princeton University Press. 272 pages. $29.95.

The title of Colin Jerolmack’s book, Up to Heaven and Down to Hell refers to a problematic aspect of American exceptionalism — the right of ownership of not just what is on the surface of your property, but also of what lies beneath it, including mineral rights (in most countries this is not the case). It comes from a common-law maxim: “Whosoever owns the soil, it is theirs up to heaven and down to hell.” In the United States, that means individual landowners are able to make deals with huge fossil fuel companies desiring to frack for gas underneath their land. In Promised Land, a film about the process starring Matt Damon, a town gets to vote on whether they want fracking or not. But, in reality, that isn’t the way it works. A representative from a gas company shows up at the landowner’s door and makes a money offer, both upfront and for as long as fracking pays, to drill on and make use of the property. In this way, the companies circumvent any community decision-making. In fact, it creates a situation where even those who resist making deals with the gas companies feel pressured to comply because their neighbors are doing so.

Although the subject of fracking may not at first glance sound compelling, Jerolmack usefully expands the topic to take in what he calls the public/private paradox. Our recent experience with the pandemic has immersed us in this concept. The United States has a much-valued tradition of individuality and freedom of choice: our culture also places tremendous value on decisions made by the individual. What happens when we are asked to work together as a community by wearing masks in public, closing businesses and schools? Something like half of the country sees it as an infringement of their rights. It doesn’t help when the president not only refuses to wear a mask but encourages others not to as well. Many Americans prize their individual freedom, even if it contributes to the deaths of hundreds of thousands of their fellow Americans! The public/private paradox Jerolmack examines boils down to this — what is good for you individually may not be good for the public at large.

Regarding fracking, Jerolmack ties it to England’s idea of the commons or common lands. That is, what should happen if fracking limits access to and enjoyment of state parks and federal lands? In addition, he sees fracking as emblematic of America’s relationship to fossil fuels. Jerolmack reminds us that “America has produced (by far) the largest share of global greenhouse gases since the industrial revolution. It represents only 4 percent of the world’s population but consumes almost a fifth of the world’s energy.” It’s as if we, like those Pennsylvanians who elect to allow fracking on their land, have collectively decided it’s fine for us to burn fossil fuels for our own needs — no matter how it affects the environment for the rest of the world.

Jerolmack does an in-depth study of an area in Pennsylvania that is located over what is called the Marcellus Shale. The gas fracked from here runs from Pennsylvania all the way to Kentucky and Tennessee and it “drives the growth in US natural gas production” according to the US Energy Information Administration. This is a predominantly rural area known as Appalachia: the setting of J.D.Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy. It is Trump country, populated by libertarians who generally do not trust the government and want to be left alone. An important element in fracking’s success is that companies such as Anadarko are able to deal directly with landowners without government interference. They accomplish this by hiring Landmen (independent contractors who interface with property owners on behalf of oil companies). Unlike environmentalists, they are able to make property owners lucrative offers.

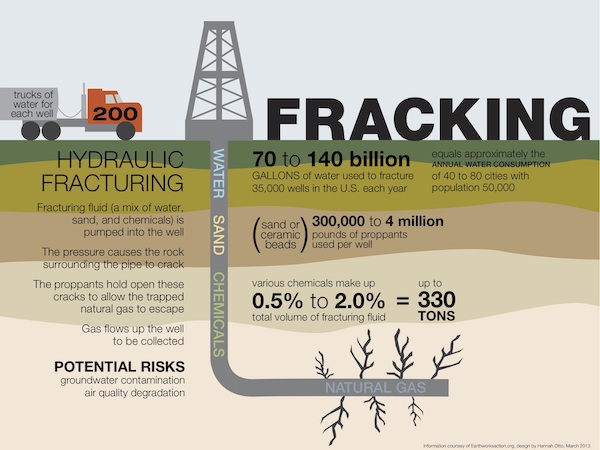

Fracking Diagram. Photo: Gove Online

Jerolmack, who recognizes the harm fracking causes to both the local area and the global environment, spends quite a bit of time trying to figure out how one might convince rural libertarians that fracking is detrimental. He has outcomes on his side: though it goes against the culture of the landowners to trust outsiders or to tell their neighbors what they should do, many property owners have been unhappy with the results of fracking. It turns out that fracking, like the lumber boom in the 1800s, follows a “boom and bust” trajectory: money and resources flood an area while the good times last and disappear when they are over. In recent years, partly due to an oil glut, the market for all fossil fuels, including gas, has plunged in value. You may remember a period last year when the price of a barrel of crude fell below zero.

Many of the cooperative locals Jerolmack interviewed have sad stories to tell. They end up moving away because of the loss of sovereignty over their land. Gas companies poison ground water, clear-cut forests and decimate once beautiful resources such as trails and rivers. Libertarians respond with concern when given honest information and are invited into the process of decision-making. But, one of the concerning takeaways from Up to Heaven and Down to Hell is that it will be difficult to persuade us that the decisions we make every day — including the policies and laws that buttress our choices in transportation, the food we eat, the way we heat and air-condition our homes and businesses — have enormous consequences, not just for us, but for the world as a whole.

Up to Heaven and Down to Hell is an excellent deep dive into the ways fracking mirrors the many problems we face as we try to change the way we think about energy, individual choice, and climate change.

Ed Meek is the author of High Tide (poems) and Luck (short stories).