Book Review: “Cheese, Wine, and Bread” — On the Menu, Confession and Fermentation

By Robert Israel

The current rage for inserting the personal/confessional in everything from cookbooks to literary criticism can go too far.

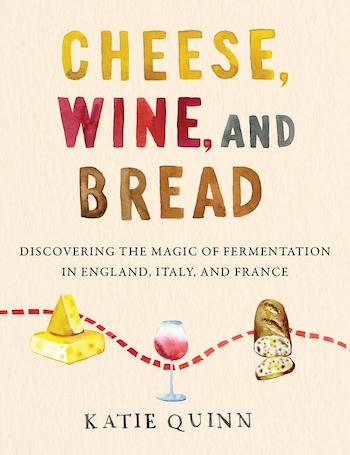

Cheese, Wine, and Bread: Discovering the Magic of Fermentation in England, Italy, and France by Katie Quinn. Harper Collins, 374 pages, $29.99.

The peripatetic Katie Quinn says she’s an “author, food journalist, YouTuber, podcaster, and host.” But that’s not an accurate list of her priorities. It’s closer to the truth to say that Quinn excels as a digital maven but falters as a disciplined writer. Her book offers ample evidence of her talents: schmooze and smile for the camera she can do. But Quinn hadn’t the patience to cut and shape this unwieldy book, whose bloated sections chronicle her European wanderings in search of recipes from cheese makers, vintners, and bread bakers.

The peripatetic Katie Quinn says she’s an “author, food journalist, YouTuber, podcaster, and host.” But that’s not an accurate list of her priorities. It’s closer to the truth to say that Quinn excels as a digital maven but falters as a disciplined writer. Her book offers ample evidence of her talents: schmooze and smile for the camera she can do. But Quinn hadn’t the patience to cut and shape this unwieldy book, whose bloated sections chronicle her European wanderings in search of recipes from cheese makers, vintners, and bread bakers.

Quinn is very much into celebrating her perky personality. But puff isn’t enough to sustain quality prose; her writing frequently ends up gasping for air — a soufflé becomes esoufflé. If only Quinn had taken the time to craft a narrative that highlighted not only her thrills and successes, but her struggles and failures. Contrasts and tensions create substance. But you won’t find that in Cheese, Wine, and Bread.

This is a made-for-YouTube book, so Quinn’s self-promotional skills predominate. There is nothing wrong with that: hyping your stuff is a venerable American job. The problem is that, after the glitter has settled, the goods have to be delivered. For example, Mark Twain was an expert huckster and arguably America’s first social media superstar. Having once worked as a journeyman in a print shop, he knew how to set type. So early in his career Twain would amble into newspaper composition rooms before his public lectures and lay out self-promotional ads in bold type that promised that ferocious animals would appear onstage during his talk (and then disclaim it in smaller type). The buzz blazed — almost all his performances sold out. Quinn boasts of being a “YouTuber, podcaster and host” with legions of followers. The difference is that Twain knew how to sell, tell – and write – damned good yarns. Quinn lacks that talent, which undercuts the overall value of this book.

Quinn has acquired bona fides to be a foodie educator. Based in London, a European center for cheese, she worked at a high-end cheese shop, doing duties at the counter, distributing nibbles on the street corner, and chatting up customers. She learns what people want and what they don’t. Exposed to a variety of cheeses, learning which pair the best with food and drink, she becomes a connoisseur. Later, Quinn takes off on a busman’s holiday to rural England to work at a dairy farm. She rolls up her sleeves and, to use her words, gets “up to my armpits in curds” as she makes cheeses. It’s the opportunity of a lifetime for a cheese lover. She captures much of the excitement of the experience, but the impact is dulled whenever she engages in her own ceaseless (and annoying) navel-gazing.

Early in the book, for instance, we read that she suffered a ski accident that resulted in a brain injury. She writes about being nursed back to health by her loving parents. We learn about her love for, and eventual marriage to, Connor, the man to whom she dedicates the book: “I’m about to marry a man who would rather have cereal five nights a week than dirty multiple dishes! But I’m in love with him! Gah, life!” she gushes. (Italics are hers.) One reference would be enough, but no such luck. Later, she revisits the brain injury story and Connor’s devotion to her, she compares his ardent letters — written and posted to her daily while she was convalescing — to the writings of “a young Ernest Hemingway.” She shares mawkish details of her holiday travels, when she and Connor journeyed to a cabin in Norway to gape at the aurora borealis. This is a considerable departure from the mission of Cheese, Wine, and Bread, which is to report on food that readers might enjoy and create for themselves.

One senses Quinn never passes a mirror, a video camera, or an i-Phone lens without being reminded that she’s among the most fortunate in all the land. The current rage for inserting the personal/confessional in everything from cookbooks to literary criticism can go too far. The aforementioned Norway cabin-cuddling yarn could easily be cut, the numerous brain injury references trimmed, and the patches of purple prose toned down. And, while we are at it, Quinn’s smarmy story about the “love” her mother kneads into her challah recipe could be eliminated along with her vulgar discussion of flatulence. My hunch is most readers stopped snickering at fart jokes in grade school.

The irony is that Quinn obviously learned many useful lessons while working on farms and vineyards, at the retail cheese shop in London, and in various kitchens. As a student, she appears to have been passionate and humble. It is unfortunate that so little of that humility appears in the pages of this book.

On the plus side, Cheese, Wine, and Bread contains many sidebars that compactly draw valuable distinctions, such as between orange and white cheddar cheese. There are enticing recipes, including one that invites readers to attempt a concoction called drunken spaghetti (pasta flavored with red wine, chopped nuts, and cheese). And Quinn’s section on baking bread, with accompanying illustrations (and synopses), is noteworthy. Readers can access the recipes — and avoid the stories — by turning to the index.

Robert Israel, an Arts Fuse contributor since 2013, can be reached at risrael_97@yahoo.com.