Film Review: Berlin International Film Festival 2021 — a Promising Virtual Detour

By David D’Arcy

This was an improved edition of the Berlin International Film Festival, and a number of films seem poised to travel widely, despite being largely ignored by the US media.

Berlin International Film Festival

The Berlin International Film Festival (March 1-5) went virtual this month. In past years at the Berlinale, as it’s called, questions arose about the quality of the selections in the event’s international competition. But this was an improved edition, and a number of films seem poised to travel widely, despite being largely ignored by the US media.

Here are a few that you’ll probably get a chance to see.

A scene from Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn

Directed by Romania’s Radu Jude, Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn is more sensible than it might sound, although Jude insists in interviews that the title in Romanian is more obscene than it is in English. It won the Golden Bear, the festival’s top award.

The action opens with a wild sex scene worthy of that title (between husband and wife), and then schoolteacher Emi (Katia Pascariu), the wife, heads in a plain gray suit across Bucharest on foot. But nothing seems right. Men on the street approach her for sex or just curse at her. A male responds obscenely when she asks him to move his car. When video of her earlier romp goes online, she’s held up to public shaming, put on trial by her school superiors in what becomes a circus of accusations that’s as petty as the show trials under Romanian communism — an era that Jude revisits in a mid-film archival tour. That’s a high bar.

Jude’s last film at the Berlinale, the elegant and savagely funny Aferim! (a Turkish word meaning “bravo”), was a road movie inspired by westerns. Characters walked (yes, just about everybody was on foot) through the abuses and institutional absurdity of the late Ottoman period. Bad Luck Banging updates Jude’s wry assessment of humanity to the present. The road movie this time is set on city streets, where chance encounters and everyday affronts exude a random foulness that epitomize the obscenity of daily life — with laughs that Jude inserts at the most painful moments.

Jude, 43, is prolific. In 2018, seven or so films ago, he made I Do Not Care if We Go Down in History as Barbarians, a look back into history (as much of his work is) that took its title from a statement made by a Romanian fascist leader known for his fervor for killing Jews during World War II. You’ll hear echoes of that hatred from the masked and socially distanced citizens at the free-for-all trial who denounce Emi, played stoically and magnificently by Pascariu.

(For another vivid look at obscenity in Romania, see the documentary Collective by Alexander Nanau, just nominated for an Academy Award. The film investigates the corruption generated by the anguish and death of burn victims who survived a discotheque fire, only to be treated with medicine that a drug company had diluted.)

A scene from From Where They Stood.

Christophe Cognet’s From Where They Stood (“À Pas Aveugles”) is a documentary that examines photographs taken by prisoners in Nazi concentration and death camps. It came as a revelation among dozens of world premieres. Who knew? In 2019, Cognet published a book in France — Eclats: Prises de vue clandestines des camps nazis — on these clandestine photos. His 2014 film Because I Was a Painter looked at art made by artists confined in the camps, including interviews with those who had survived.

The pictures vary from shocking to ordinary, given the circumstances. Some show daily routines in Buchenwald, where prisoners obtained cameras because of their assigned jobs. Another set of images shows women “rabbits” who survived medical experiments at the Ravensbrück camp: they are posing (some smiling) in fashionable clothes that had probably been taken from prisoners on their arrival. In some of these shots, the women roll down their stockings to display their wounds.

Photographs at the Birkenau death camp, taken and later smuggled out by members of the camp resistance, show women undressing near a gas chamber. In other Birkenau pictures, prisoners tasked with disposing of bodies walk in a sea of corpses as they prepare an open-air burning pit after a crematorium breaks down.

Walking through those sites, Cognet explains in rigorous detail how these pictures were taken and how they managed to escape destruction after the SS burned the camps to destroy any trace of the Final Solution.

Pictures that were published after the war were sometimes altered. A person shown sunbathing in Buchenwald with a smokestack in the background was removed, so that no one would mistakenly view confinement there as a holiday. Cognet returns the figure to the image. Photographs of women heading to their deaths at Birkenau were also touched up.

Using hand-held frames with transparent exposures of pictures taken by prisoners, Cognet matches those images at locations at the same sites today. The exact overlays are revealing. In the haunting new normal of tourism, visitors with cell phones take their own photos in places where so many suffered.

From Where They Stood begins and ends with Cognet and his team examining bone fragments (éclats) that rise to the surface in the rain from mass graves in Birkenau. His visual excavation shows us how the pictures surfaced as fragmentary remains of horror.

Films from Iran have long been a regular part of the Berlinale, even when filmmakers were banned from traveling to present them. Ballad of a White Cow, co-directed by Behtash Sanaeeha and the actress Maryam Moghaddam, begins in prison were a man is being executed for a crime he didn’t commit. Mina (Moghaddam), his widow, clashes with her husband’s family: we see how the death penalty damages families, not just individuals. A year later, Mina is working in a milk factory to support her deaf daughter. She is informed that her husband was wrongly killed and that she’ll receive compensation. Soon she meets a man who not only finds her a pricey new apartment but continues to help her and her daughter. Mina’s late husband’s conservative family disapproves that she’s living on her own and rumors spread. Complications grow when it is revealed that the strange generous man was one of the judges who sentenced Mina’s husband.

This is a bare-boned monochrome portrait of a woman’s resilience, where nothing in the filmmaking seems sacrificed despite a minimal budget. Moghaddam’s acting holds you through this woman’s battle for her dignity and autonomy against age-old family norms, restrictive religious practices, and judicial incompetence. The film’s questioning — oblique and direct — of the barriers Mina faces in Iran is bold, given the penalties for questioning everyday oppression there. The white cow in the title (seen in the film’s opening at the prison) refers to a passage in the Koran in which Moses demands a sacrifice for a man’s death.

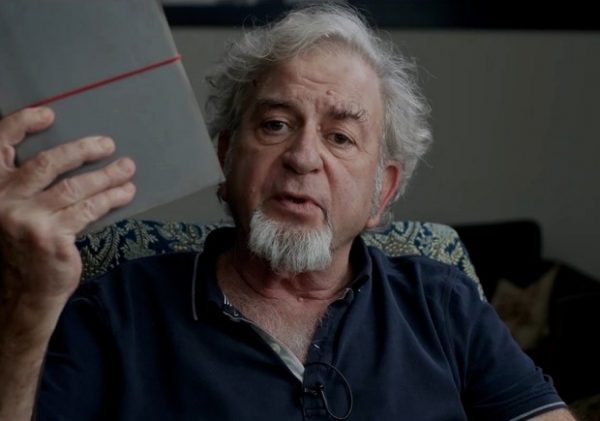

Director Avi Mograbi in a scene from The First 54 Years – An Abbreviated Manual for Military Occupation,

Films from elsewhere in the Middle East had strong representation at the Berlinale. Director Avi Mograbi’s The First 54 Years – An Abbreviated Manual for Military Occupation came from Israel, where the filmmaker has been a longtime critic of Israeli occupation of Palestinian land. This time he revisits the end of the Six Day War (1967), examining how settlers and occupying soldiers did what they could to make the occupation punitive — closing essential roads on the West Bank, dynamiting infrastructure on the Gaza Strip, murdering Palestinian Authority policemen after a terrorist attack.

Now 64, Mograbi, resolute and measured, with a beard that gives him the look of an Old Testament prophet, narrates the documentary, relying on former soldiers in the Occupied Territories for testimony. Their actions, as the veterans recall them, were harsh and petty, with suggestions that the vile behavior is continuing to this day. Archival footage adds to the evidence.

The Berlinale is a major annual market for Israeli films of all kinds. While Mograbi is accustomed to being ignored by most of the film public in his own country, he has garnered an international audience. Co-produced with France, Germany, and Finland, The First 54 Years will travel widely.

So, I hope, will Ferit Karahan’s Turkish drama Brother’s Keeper, which unfolds in a state boarding school for Kurdish boys, isolated by heavy snow throughout the winter. Rules are strict. Punishment is severe. The remote institution is also a catch-basin for political hacks, so corruption reigns. When a group of boys is punished — and one of them falls seriously sick — the seams in this de facto prison start showing. The boys know the truth — their warders are at fault — as the sick child’s condition worsens. This taut and spare portrait of an institution overwhelmed by rot — inner and outer — can easily be seen as an allegory for the ills of Turkish politics. There will be inevitable comparisons to Jean Vigo’s Zero de Conduite or Francois Truffaut’s The 400 Blows, but Karahan doesn’t seem interested in quoting from elders in his vision of adult meltdown.

Set in grayish enclosed spaces, Brother’s Keeper plays like a refined theater production. You’re left wondering how the director got such convincing performances out of such young boys. I expect it to win over any audience that it reaches — besides the ministries in Ankara.

A scene from A Cop Movie.

Corruption is also at the core of Mexican Alonso Ruizpalacios’s A Cop Movie, a romance between two police officers in Mexico City. What starts as a charmingly scripted tale of two people who find each other on the police force is flipped on its head via a reality check when the real police couple (who inspired the film) talk about the reprisals that followed after they enforced the law on a bar owner who had paid off their boss.

If that hybrid approach sounds convoluted, it is. Ruizpalacios places (and films) two fetching actors going through police training and making their way onto the police force. Then the director brings on the police officers on whom those characters are based in order to remind you that police work at the low end of the food chain can be thankless, or a lot worse. At first, the film seems to want to make you think you will reverse your attitudes toward Mexican cops — and it does no such thing.

Ruizpalacios was at the Berlinale in 2018 with Museum, a scripted tale of a theft at the much-visited and much-loved National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City, based on an actual (and successful) robbery by amateurs in 1985. What killed the gambit in the film and the heist was that they couldn’t sell what they stole. Now the director has gone down-market to a job with a troubled reputation, ill-paid policemen who pad their meager salaries with bribes. We are given inside information from cops themselves about how their bad reputation has been earned.

If projected schedules go according to plan, the Berlinale will resume with an in-person version of its virtual program in June, right before the Cannes Film Festival. As with so much else in the past year, no one is sure of what to expect.

David D’Arcy, who lives in New York, is a programmer for the Haifa International Film Festival in Israel. He writes about art for many publications, including the Art Newspaper. He produced and co-wrote the documentary Portrait of Wally (2012), about the fight over a Nazi-looted painting found at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan.

Tagged: Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn, Berlin International Film Festival 2021, David D'Arcy