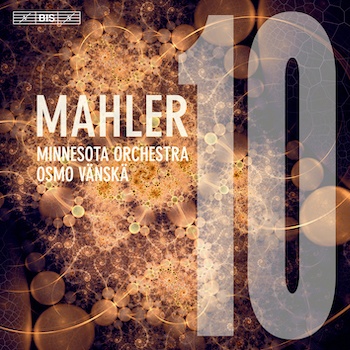

Classical Album Review: Minnesota Orchestra plays Mahler 10

By Jonathan Blumhofer

There’s much to admire in the color, character, and urgency of the Minnesotans’ playing and the overall strong direction from conductor Osmo Vänskä.

Gustav Mahler’s most controversial symphony, the Tenth, is back, with a new recording from Osmo Vänskä and the Minnesota Orchestra as part of their ongoing Mahler symphony cycle for Bis.

Gustav Mahler’s most controversial symphony, the Tenth, is back, with a new recording from Osmo Vänskä and the Minnesota Orchestra as part of their ongoing Mahler symphony cycle for Bis.

Left incomplete at Mahler’s death in 1911, the Tenth quickly gained a reputation for being many things it wasn’t: an unfinishable vision of the hereafter (according to Arnold Schoenberg), a draft of music that ought to be consigned to the flames (Richard Specht), and a repetition of the same composer’s death-haunted Ninth Symphony (Leonard Bernstein), among them.

Yet Mahler had left behind far more than incoherent, redundant sketches: he had, in fact, drafted the work in full during the tumultuous summer of 1910, scored its first movement, much of the second, and had begun orchestrating the central one (cryptically called “Purgatorio”). After his death, various of Mahler’s contemporaries attempted to finish the Symphony, but it wasn’t until British musicologist Deryck Cooke’s first performing version of the Tenth was published in the 1960s that the piece finally began to creep into the repertoire.

Even so, it wasn’t universally accepted: Bernstein, for one, famously refused to conduct any part of it other than the opening Adagio, arguing that that movement was the only one completely written by Mahler. He had a point: Cooke filled in a handful of texturally-bare spots in his completion with Mahler-like counterpoint, and the orchestration, while taking its lead from Mahler’s notes in the draft, is largely Cooke’s (as well as Colin and David Matthews’, who aided the revisions of Cooke’s performing edition).

But the overwhelming percentage of the notes – not to mention the whole of the Tenth’s form, structure, and expressive content – remain Mahler’s. Certainly, had he lived, the Tenth would have sounded differently than it does in Cooke’s completion. Then again, so would Das Lied von der Erde and the Ninth Symphony, both of which Mahler surely would have revised had he lived to hear them rehearsed and performed, as was his habit. But I’m beginning to digress.

All this to say, the Tenth is a special piece, one that’s still not encountered often enough in the concert hall or too regularly recorded. So it’s commendable that Vänskä and his band have committed a full account of it to disc (for contrast, Michael Tilson Thomas and the San Francisco Symphony, in their ‘00s Mahler cycle, stuck to just the Adagio). They play the third and final version of Cooke’s completion and, by and large, do it proud.

In general, Vänskä’s approach to Mahler is Apollonian rather than Dionysian, which may not be to all tastes (it certainly hasn’t been to mine in some earlier installments in this cycle). Here, though, his expressive coolness pays dividends.

True, in neo-Bernstein fashion, Vänskä stretches out the big, opening Adagio to about the music’s breaking point. Yet there’s a bracing clarity to the ensemble’s playing. Indeed, Mahler’s counterpoint always speaks, lovely solos (especially from the string principals) abound, and there’s a good sense of shape to the proceedings (thanks, in part, to the Minnesotans’ big dynamic contrasts and close attention to articulative detail). To top everything off, the movement’s dissonant climax is fittingly explosive.

In the first of the Symphony’s two Scherzi, Vänskä’s forces remain nimble and texturally transparent despite the music’s tricky, shifting meters. They also imbue its contrasting ländler theme with plenty of warmth.

Osmo Vänskä and the Minnesota Symphony performing Mahler. Photo: Minnesota Symphony.

Some uneven moments arrive in the following pair of movements. The central “Purgatorio” feels a hair sluggish and impersonal, though there’s a nice edge to certain attack-like gestures within. Meanwhile, the second Scherzo goes too far in the opposite direction, driving over-aggressively where it should breathe (mostly in the Allegro pesante sections): the effect is technically dazzling but expressively frenetic. That said, the movement’s easygoing, waltz-like passages swing with carefree élan and its climaxes come out of nowhere to land mightily.

Many of those latter qualities also mark the Minnesotans’ account of the finale, which is highlighted by intense military drum tattoos; radiant flute solos; and, over the closing pages, beautifully-matched articulations and tonal blending between woodwinds, horns, and strings. Vänskä’s direction ensures a natural, purposeful unfolding of the musical line, though the finale’s climax is marred by the horns’ lackluster reiteration of the opening movement’s refrain.

The last isn’t a dealbreaker for either that movement or the larger performance. But, taken together with the aforementioned problem-spots, this recording doesn’t quite break into the top tier of Mahler/Cooke Tens (among which I’d count Michael Gielen’s, Thomas Dausgaard’s, Simon Rattle’s first, and Gianandrea Noseda’s).

Even so, there’s much to admire in the color, character, and urgency of the Minnesotans’ playing and the overall strong direction from Vänskä; to be sure, this is a Mahler cycle that seems to be building in purpose and quality as it approaches its denouement.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.