Book Review: “Savage Kiss” — Children’s Criminal Crusade

By Lucas Spiro

Maybe the greatest value of Saviano’s narratives is that they rebuke the complicity of silence; they are acts of dissent that refuse to kowtow to the oppressive omertà.

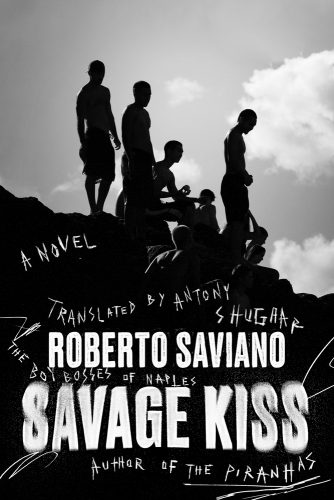

Savage Kiss: A Novel by Roberto Saviano. Translated from the Italian by Anthony Shugar. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 400 pages, $28.

Buy at Bookshop

Roberto Saviano’s latest novel, Savage Kiss, has the same disclaimer as its prequel, The Piranhas: The Boy Bosses of Naples. His coda to the legal boilerplate reads: “The same disclaimer that appears at the beginning of the movie Hands over the City applies to my novel: The characters and events that appear here are imaginary; what is authentic, on the other hand, is the social and environmental reality that produces them.” The reference is to Francesco Rosi’s 1963 political drama about a Neapolitan real estate developer and city councilor, played by Rod Steiger, who uses public power and private interest to enrich himself. A communist politician leads a failed inquiry — which had the potential to reveal systemic municipal corruption — into a building collapse linked to the developer.

Of course, the disclaimer for Rosi and Saviano amounts to a sly joke. Rosi’s film before Hands, Salvatore Giuliano, sparked “the formation of a parliamentary commission in Sicily to investigate the influence of the Mafia.” Hands over the City hit even closer to home. This is fiction shaped to implicate political decadence, to combat real and corrupt social conditions. Critic Stuart Klawans puts it well in an essay on Hands over the City.

Rosi had taken the immediacy of neorealism — its quasidocumetary presentation of real people in real locations, acting out real social problems — and merged it with a Wellesian love of showmanship, melancholy, baroque contrivance, and enigma. Nowhere is this combination more outlandishly theatrical, yet absolutely authentic, than in Hands over the City, where actual members of the Naples City Council, playing themselves, in their own chamber, lift up their arms in protest to cry, “Our hands are clean!”

Since the 2006 publication of his seminal book Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System, Saviano has needed various forms of police protection, safeguarding that has included long periods of self-isolation. That’s because of the death threats from the mobsters he has outed publicly and in print. The characters in his novels may be fictional, but his vicious literary assault in Gomorrah — one of the 21st century’s most compelling hybrids of political exposé and memoir — has pitted him against the all-encompassing power of the camorra, southern Italy’s sophisticated crime syndicate whose tentacles extend well beyond the city’s limits. “I know and I can prove it,” is one of Saviano’s mantras in Gomorrah. Most of those in the city admit this truth, though it hasn’t changed things. Still, you can’t unring the bell; Saviano has courageously chosen a side. No matter what kind of disclaimer he puts in front of his novels, Saviano’s books are as political as they are artistic, regardless of the “imaginary” quality of his characters and their actions. His narratives open him up to intimidation from the barbaric forces his stories dissect. He was already there, of course. He was born in it. To struggle against the webs of Naples’s criminal system is to choose to live freely — and under duress.

Savage Kiss follows the evolution of the paranza, who appear in The Piranhas. “Paranza is a word for boats that go out to catch fish through the trickery of light. The new sun is electric, the light occupies the water, it takes possession of it, and the fish come looking for it, they put their trust in it. They put their trust in life…” The word also refers to a criminal gang of young people, small fry in a sea filled with older, more ferocious mob bosses. Surrounded by big fish as they grow up, young Neapolitans learn to love, adore, and depend on the influence of the camorra honchos, to respect their thuggish power and the riches that come with it. Nicolas, a kid from the Forcella neighborhood at the city’s historic center, gathers up his paranza from among his classmates and friends, convincing them that they can take over the entire city. This story resembles the real life attempts of a younger generation, sometimes no older than 18 years old, to displace the old guard. Ill, imprisoned, or isolated in self-made prisons (shields against the authorities and rival bosses), these corrupt seniors are seen by the young as vulnerable.

Author Roberto Saviano. Photo: Piero Pompili.

At the beginning of Savage Kiss, Nicolas, nicknamed “Maraja,” and his paranza have secured a sizable portion of Naples’s street narcotics trade. They have pulled off this coup by allowing the local independent drug pushers to sell drugs from other suppliers — so long as they sell it a higher price than those supplied by the paranza. They police this profitable arrangement via anarchic violence as well as a superior product. In addition to the drug dealing, some of the paranza‘s scams reflect the know-how of a generation of kids raised online. Drone (named for his love of tech gadgets) devises a scheme that uses TripAdvisor as leverage over the restaurants, bars, and cafes the gang extorts. Drone encourages his pushers to sell at an even deeper discount — in exchange for online ratings. The higher the ratings, the more money the blackmailed restaurants make, maximizing Drone’s revenue. It’s simplistic and juvenile, but it demonstrates the cultural and generational smarts of these aspiring gangsters.

As the gang’s criminal profile raises, so do the risks. Betrayals and bodies pile up. But Nicolas is undeterred, driven by destiny, megalomania, and a chip on his shoulder the size of the Castel Nuovo. Neapolitans are familiar with this kind of hefty hubris. Since the Risorgimento, Naples has often been seen by the dominant northern republics as a provincial backwater of crime, the city’s mayhem committed by people who don’t even speak proper Italian. Thus the rise of the Neapolitan criminal world has meant a resurgence of urban pride, a sense of self-worth assisted by the charisma of wealth and infamy. This north-south dynamic is dramatized in Savage Kiss when the paranza’s exploits bring them further afield than they’ve ever been before. This includes a trip to Rome, the first time away from Naples for most of them. Their insecurity about home is expressed in predictable ways: “our metro down in Naples doesn’t stink like this” and “up here no one even looks you in the face, they’re all too scared all the time.” The gang’s leader is more narrowly focused on discerning the pecking order: “Nicolas…was looking at the people. Whatever detail, he wanted to gauge it. How much do you earn? How much are you worth? Who are you paying? Everything had a worth that could be totted up…. To him, everything came down to a hierarchy of money and power.” When he tallies up the worth of what he has on him — clothes, jewelry — he doesn’t reach a plausible conclusion. He still has a lot to learn about real power.

That innocence comes from the fact that the Savage Kiss deals with children. The youngest member of the crew, Biscottino, is no more than 13 or 14. Ironically, he is made to carry some of the heaviest weight throughout the novel. In David Simon’s television crime drama The Wire, a retired police officer becomes involved in an academic study about youth crime in Baltimore. The researchers want to study teenagers and young adults. The retired officer warns them that those subjects would be too old. To reach at-risk young people they need to intervene before they get to high school. These Neapolitan kids are examples of this reality. Most of the paranza come from the middle class. Nicolas chooses them not because they’re desperate, though some are, but because he knows the same burning desire for success has been inculcated in all of them. Their parents expect their kids to be winners, to rise above the competition. Nicolas cultivates those dreams of domination, choosing kids who desire to be boss, who want to control or rip off others even when they know it’s wrong.

While we feel sorry for what these kids are doing to their lives, Saviano is not trying to create sympathetic portraits of murderers and drug dealers. He’s chosen his side, though it’s obvious his heart breaks for the young blood on which the dishonest system feeds. The small fish are drawn into the paranza, hooked by an artificial source of light, until the nets lift them out of the sea and they meet their fate. What kind of change the author intends is not as apparent in his novels than in his nonfiction work. Savage Kiss is a crime novel that lacks Gomorrah‘s value as a work of moral protest. The possibility here of demanding justice, because of the emphasis on domesticity, is cloudy. Nicolas’s mother is inexcusably devoted to her son and his rise to power. Then there are enablers who are more conflicted but don’t see a way out. One parent laments that “the destiny of being a mother here is to be a soldier’s mother. Have them, raise them, and then send them to die. It’s just there’s no medal for this war, just shame and contempt.” She goes on to say the shame and contempt, “lo scourno mio,” comes from “the fact that [she] live[s] off the money that [her] son earns.”

Of course, Saviano now lives off the money he makes from telling stories about the camorra. Every book he’s ever written has been a success, often turned into a movie or television series so quickly that it’s hard to imagine the rights weren’t sold before the book was published. Yes, he lives a compromised life, but he’s compensated for it, and that financial gain only exists because he cannot live outside of the camorra system. To paraphrase Mussolini: everything within the system; nothing outside the system; nothing against the system. How then do we judge Saviano’s body of work? Gomorrah is, undoubtedly, a kind of masterpiece. His novels have exciting and daring plots, but don’t leap off the page and come alive with nearly the same force as his personal story does. In translation his fiction reads awkwardly (perhaps his novels are smoother to consume in the original Italian?). The fact is, they probably make better movies than books. I feel strange suggesting a man living under constant fear should be a better writer. Maybe the greatest value of his narratives is that they rebuke the complicity of silence; they are acts of dissent that refuse to kowtow to the oppressive omertà. That’s admirable. The best one might hope for is that a Neapolitan kid picks up his volumes and recognizes the cojones of someone who stands up to the camorra. If he can’t reach them with the books, maybe they’ll watch the movies on their smartphones.

Klawan argues that Hands over the City, despite its “despairing conclusion,” makes audiences “leave the movie feeling invigorated, not cynical.” He asks if this is “a triumph of form over content” and proposes that its about “a triumph of love” instead. The film “radiates affection for the streets and alleys of Rosi’s hometown, its workingmen and housewives – even at times, for its grotesque and funny grafters.” On the one hand, Saviano’s Naples is a very different place at a very different time: Saviano is far more cynical. Still, both artists radiate affection for the city. Maybe the best characterization of Saviano’s postmillennial attitude would be to see it as a volatile mix of cynicism and affection. Today’s Naples is Rosi’s — five decades of corruption later. After all the movies, books, investigations, arrests, and murders, is it possible to make a reasonable case that anything has seriously changed for the better? Saviano’s recent articles talk about how organized crime has found ways to become rich exploiting the pandemic economy. And they are not the only ones. The world’s billionaires have added millions to their wealth over the past year while countless others have needlessly died or gone destitute.

Lucas Spiro is a writer living in Dublin.