Arts Remembrance: Art Critic and Historian Barbara Rose

By Peter Walsh

At a time when ambitious women of any sort were often harshly criticized for pursuing a professional career, Barbara Rose only forged on.

The late Barbara Rose in the 2018 documentary The Price of Everything. Photo: HBO

Barbara Rose seemed destined for a conventional academic career when, in 1961, she visited Pamplona, Spain, on a Fulbright. There she hung out with a young, ambitious Princeton grad named Frank Stella. Not long after, in London, they were married. Rose, born in Depression Era Washington, DC, to a liquor store owner and a homemaker, branched out on a different path.

Rose and her husband soon had two children. Though she never completed her Columbia University Ph.D. dissertation, on 16th-century Spanish painting, she never succumbed, like so many educated women of her generation, to the demands of child rearing and the rapidly rising fame of her husband. Instead, she began gestating a career of her own in the bohemian-bourgeois world of the downtown Manhattan art scene. She and her husband settled in the newly trendy SoHo district — soon to be the epicenter of contemporary art — with its recycled Victorian factory buildings containing spacious artist lofts and major art galleries.

Stella quickly became one of the leading American painters of the decade and other now-famous artists, most of whom also worked in the rising “Minimalist” style, were family friends. The circle included Carl Andre, Larry Poons, and Donald Judd, and other figures in the downtown scene, and the young Formalist critic and academic Michael Fried, then completing a Ph.D. in art history at Harvard. There he organized an important exhibition at the Fogg Art Museum that included Frank Stella as a central figure in American contemporary art.

Encouraged by Fried and others, Rose began publishing art criticism in 1962. She was by no means a detached observer but began to develop her famous habits of visiting artists in their studios and grilling them, as if they were her dinner guests, about anything she wanted to know. An attractive, slim blonde with a vivid and trenchant personality (she was known, at her lectures, to argue fine points with members of her audience), she became a familiar figure in an art community of young American artists who were finding fame and fortune previous generations did not even dare dream of. At a time when ambitious women of any sort were often harshly criticized for pursuing a professional career, she only forged on.

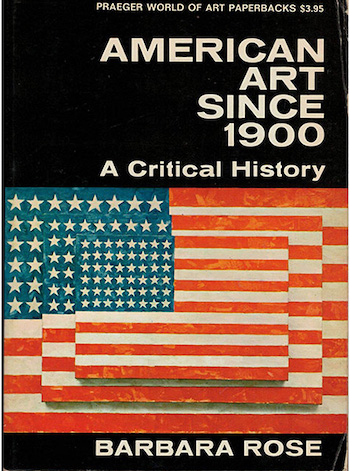

In 1965 Rose published, in the magazine Art in America, an essay titled (by her editor, Rose claimed) “ABC Art,” regarded as a seminal document in the art history of Minimalism, the austere, impersonal abstract art then practiced by her husband and many of their friends. In 1967, her most famous book, American Art Since 1900: A Critical History, appeared. A fast-paced, relatively short survey of the major figures and movements in American art for roughly the first half of the century, it was widely assigned in undergraduate art history classes. It was well known to anyone studying contemporary art in American colleges and universities in the ’70s.

In 1969, she and Frank Stella divorced. She was married, in all, three times to two different men, finally settling down, in 2009, with her first and fourth husband, Richard B. Du Boff, an economic historian and professor at Bryn Mawr to whom she was previously briefly married in 1959.

As the ’70s turned into the ’80s, Rose embarked on a career as something of a public intellectual. Though she was never as famous or as visible as her sometime rival, the Australian-born critic Robert Hughes, she wore a bewildering variety of hats, often simultaneously, holding almost every sort of position her background allowed. She was art critic at New York magazine and Vogue and served as editor-in-chief of the Journal of Art. She wrote important monographs on Helen Frankenthaler, Magdalena Abakanowicz, and other women artists and remained a leading champion of female artists and sculptors though much of her career. She taught at Sarah Lawrence, Yale, Hunter College, the University of California, Irvine, and the University of California, San Diego. She organized major exhibitions and was for several years a curator at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. She produced eight documentary films. She even continued her early interests in Spanish art and culture and maintained a home in Spain. In 2010, the Spanish government awarded her the Order of Isabella the Catholic for her contributions to art history and Spanish culture.

As the ’70s turned into the ’80s, Rose embarked on a career as something of a public intellectual. Though she was never as famous or as visible as her sometime rival, the Australian-born critic Robert Hughes, she wore a bewildering variety of hats, often simultaneously, holding almost every sort of position her background allowed. She was art critic at New York magazine and Vogue and served as editor-in-chief of the Journal of Art. She wrote important monographs on Helen Frankenthaler, Magdalena Abakanowicz, and other women artists and remained a leading champion of female artists and sculptors though much of her career. She taught at Sarah Lawrence, Yale, Hunter College, the University of California, Irvine, and the University of California, San Diego. She organized major exhibitions and was for several years a curator at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. She produced eight documentary films. She even continued her early interests in Spanish art and culture and maintained a home in Spain. In 2010, the Spanish government awarded her the Order of Isabella the Catholic for her contributions to art history and Spanish culture.

By the end of the ’60s, Rose moderated her Formalist positions and loosened her close embrace of Minimalism; still, inevitably she began to look Old School. Her critical positions, once avant-garde and central to the moment, were perceived as conservative and even reactionary. Her thinking continued to reflect roots put down in the early ’60s, from aesthetic theses proclaimed by Fried, critic Clement Greenberg, and other Formalists: painting was supreme, and abstract painting, with a lineage reaching from the Russian Constructivists through the Abstract Expressionists and Minimalists, transcended everything else. Although she spoke approvingly of Warhol when his reputation was at a low ebb, she never quite reconciled to the realist movements that came as the late 20th century turned into the early 21st. Photography, in particular, she considered an inferior art, even during a period when it became an increasingly central medium as photographic techniques and aesthetics became more and more important to painting.

The tenets of Formalism held that only the visible image was central to art criticism. The belief that nonvisual ideas, political context, even the artist’s biography were essentially sidebars to appreciation began to seem dated in an era when socially engaged imagery and the identity of the artist — political, racial, sexual — could seem as important as the work itself.

Rose died on December 25 in, of all places, Concord, NH, where her son, a doctor, works. He brought her to New Hampshire several weeks before she died because her husband had been injured in a terrible accident and could no longer care for her. She had been very ill from a recurrence of breast cancer. She was 84. But all is not yet silence. In her last years she had completed a memoir, yet to be published, which will no doubt contain her concluding arguments.

Peter Walsh has worked as a staff member or consultant to such museums as the Harvard Art Museums, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Davis Museum at Wellesley College, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, and the Boston Athenaeum. As an art historian and media scholar, he has lectured in Boston, New York, Chicago, Toronto, San Francisco, London, and Milan, among other cities, and has presented papers at MIT eight times. He has published in American and European newspapers, journals, and in anthologies. In recent years, he began a career as an actor and has since worked on more than 80 projects, including theater, national television, and such award-winning films as Spotlight, The Second Life, and Brute Sanity. He is a graduate of Oberlin College and Harvard University.