Book Review: The Books of András Koerner — Acts of Wondrous Remembrance

By Susan Miron

Writer András Koerner has dedicated himself, lovingly and brilliantly, to assiduously reconstruct the lives of ordinary Jews in Hungary before the Shoah.

Before I discovered András Koerner’s quartet of books about the vanished world of Hungarian Jews, I knew only of their mass deportations and deaths in 1944. Born in 1940, Koerner was a child living in Budapest during the war; as a writer, he has been less interested in the Shoah than in assiduously reconstructing ordinary Jewish lives before the horrific events that no one among the Hungarian Jews could have anticipated. His extraordinary project, an epic act of loving memory, is dedicated to reminding us of their lives through concrete details: recipe by recipe, one moving photograph and artifact after another. As we say in Jewish prayer, he has brought the dead to life.

Before I discovered András Koerner’s quartet of books about the vanished world of Hungarian Jews, I knew only of their mass deportations and deaths in 1944. Born in 1940, Koerner was a child living in Budapest during the war; as a writer, he has been less interested in the Shoah than in assiduously reconstructing ordinary Jewish lives before the horrific events that no one among the Hungarian Jews could have anticipated. His extraordinary project, an epic act of loving memory, is dedicated to reminding us of their lives through concrete details: recipe by recipe, one moving photograph and artifact after another. As we say in Jewish prayer, he has brought the dead to life.

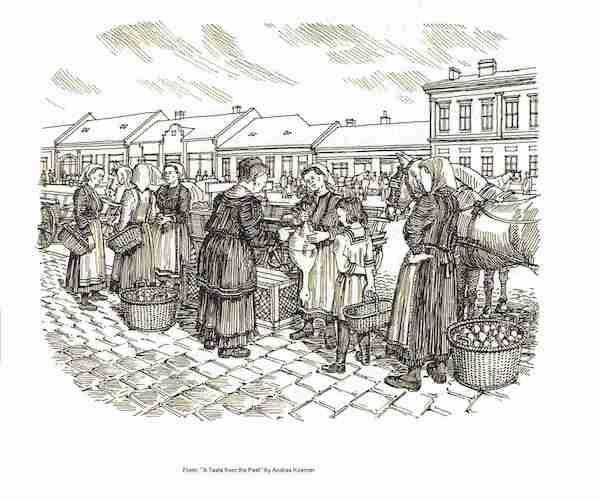

What sparked my reading marathon was the discovery of his Jewish Cuisine in Hungary, A Cultural History with 83 Authentic Recipes (CEU Press), a recent winner of a National Jewish Book Award (in a category created just to honor this volume). This is a rigorously researched, engagingly written recreation of daily life filled with rarely seen photographs and pen-and-ink illustrations by Koerner himself. I adored this book, and immediately immersed myself in his three earlier volumes about the lives of Hungarian Jews: A Taste of the Past: The Daily Life and Cooking of a 19th-Century Hungarian Jewish Homemaker (A Cultural History with 85 Recipes Adapted for the Modern Cook) (University Press of New England, 2004); and both volumes of How They Lived: The Everyday Lives of Hungarian Jews 1867-1940 (CEU Press, 2015, 2016).

Like his father, Koerner had a very successful career as an architect. He has never envisioned a second career as a writer; his books would never have happened had he not decided to commute from New York to Budapest to tape-record his ailing mother. During this engrossing joint project his mother reminisced in remarkable detail about the world of her grandmother, with whom she lived in Moson, Hungary until she was six.

Koerner’s mother’s prodigious memory and his great-grandmother’s letters offer a rare, detailed firsthand account of an anachronistic way of life, recreated in A Taste of the Past: “My great-grandparents were typical of many middle-class Jews living in small Hungarian towns, practicing a lifestyle that disappeared due to the virtually total annihilation of Hungarian provincial Jewry in 1944 with such an abruptness, that we have very few detailed descriptions of it. The fact that my great-grandparents had been born as far back as 1838 and 1851 made her account all the more valuable.” “I think,” he told The Times of Israel, “the reason why I feel (food) is important is because it is such a central aspect of a culture and everyday life.… Because of its centrality in the lives of Jews, it can reflect all kinds of things of importance in people’s identity and lives, such as religion, ancestry” as well as “someone’s relationship to modern life, and whether they are opposing change or embracing change…. The profusion of food traditions and rituals has been crucial in maintaining the cohesion of Jews as a group.”

The cache of recipes penned, the first dating from 1869, by his great-grandmother, Therese Baruch, is a remarkable document, possibly the oldest extant handwritten collection of Jewish recipes from Hungary. These recipes, many of dishes served on the Sabbath and Jewish festivals, between meals and at afternoon tea, are invaluable revelations of a woman’s life as seen through her household duties. Koerner focuses on the objects, food, and people that were an integral part of his great-grandmother’s everyday existence. These alluring pages rescue a way of life from oblivion via an indelible portrait of an observant Jewish woman who serves as a representative of her entire community. Much is illuminated through her recipes and her great-grandson’s loving illustrations.

A Taste of the Past irresistibly combines storytelling, history, and enticing recipes that detail such typical Jewish dishes as stuffed goose neck along with an array of kugels and desserts, including matzo fritters and flódni, a pastry with four kinds of filling in its layers. My sweet tooth led me to dream of making the breads, macaroon tortes, fluden, chocolate Gugelhuph, gooseberry sauce for boiled beef, plum-filled bread dumplings, and almost all of the 17 warm desserts. But the recipe that I will most likely make for dinner is fish with walnut-vegetable sauce. Of course, this is far more than a recipe book, but A Taste of the Past would make a wonderful present for anyone who loves Central European history or exotic cookbooks.

Historian András Koerner. Photo: Wiki Common.

A profusion of extraordinary old photographs are at the heart of Koerner’s indispensable How They Lived: The Everyday Lives of Hungarian. Jews. 1867-1940. “The problem,” he writes, “was not so much finding new, previously unknown photos (though of course I managed to find quite a few), but to organize them so that they become parts of a cohesive narrative. Also, there are some subjects, like people’s clothing and the apartment furnishings which tell us about their mentalities that can be better studied with the help of photos than by text alone.” He was surprised to discover that he was filling in a lacuna. Although there were books of historical photographs about the daily lives of Polish, Russian, German, and American Jews in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, he argues that “to this day nobody has published a comprehensive photograph record of the daily lives of Jews in the different regions of Hungary before the Holocaust.”

Koerner has addressed this omission dazzlingly, exploring pre-Shoah Jewish life in Hungary in these two beautifully produced, museum-quality tomes. Volume one includes sections dedicated to “What They Looked Like” (my favorite section), “Where They Lived, and Where They Worked.” Volume two deals with topics such as family, religious and social life, learning, military life, vacationing, sports, and charity. The book’s profusion of haunting sepia pictures, which were scattered about in various archives, museums, and publications, tell a powerful story. There’s at least one striking photograph on each page: moving through these pictures, from one shot to another, was, at least for this reader, a deeply emotional experience, a near-shattering intimation of an extinct culture. A rich and vibrant world that existed before the Holocaust, irreversibly gone now for 76 years, poignantly resurrected.

Susan Miron, a harpist, has been a book reviewer for over 30 years for a large variety of literary publications and newspapers. Her fields of expertise were East and Central European, Irish, and Israeli literature. Susan covers classical music for the Arts Fuse and the Boston Musical Intelligencer.

Tagged: András Koerner’, Holocaust, Hungary, Jewish Cuisine in Hungary, Jews, Shoah, cookbook

Fabulous review. I am enticed by the loving descriptions of the recipes and old photographs. Anxious to get my hands on the book to get the recipe for flodni first and foremost.

Among other places, Amazon — around $45 in paperback — though I would suggest ordering through your local bookstore …