Film Review: “Wojnarowicz: F**K YOU F*GGOT F**KER” — Homage to a Perpetual Rebel

By Peter Walsh

The documentary covers a lot of dark and tragic territory, but it remains entertaining throughout, no doubt more than anything else from its skill in capturing the fierce, tender, acidic, brilliant, and ultimately inextinguishable energy of its subject, artist David Wojnarowicz.

Wojnarowicz: F**K YOU F*GGOT F**KER, directed by Chris McKim. Currently streaming on the DOC NYC site through November 19. Link is here

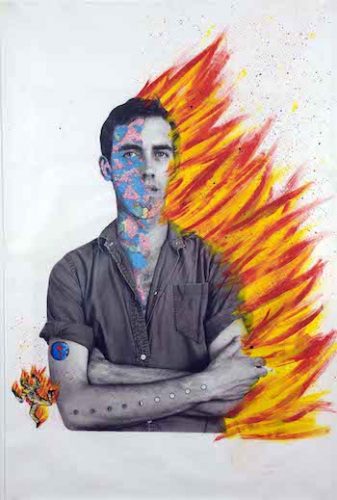

David Wojnarowicz with Tom Warren. Self Portrait of David Wojnarowicz , 1983-84. Photo: Courtesy of the artist, the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P.P.O.W.

Art history hasn’t quite digested David Wojnarowicz: too much fiery rhetoric (a personal emblem is a burning house), too many sharp edges, too much ground glass. The artist, who died of AIDS in 1992 at the age of 37, hated pretty much everything about the commercial art world and did pretty much everything he could think of to make himself unacceptable to it. Being beyond the reach of polite, art collecting society was part of his aesthetic home (his mentor, sometime lover, and intense friend Peter Hujar, posthumously recognized as one of the great American photographers of the 20th century, was known for having “hung up on every photograph dealer in the Western World.”)

Subject of numerous books and retrospectives at major art museums, Wojnarowicz’s work is surprisingly hard to see. Museums, these days eagerly inclusive, acquire his work as part of their LGBTQ+ portfolio. But they tend to actually exhibit mostly the milder, less offensive pieces, such as the multiple One Day This Kid (1990), which features an innocuous childhood photograph of the artist surrounded by a heated text which is nevertheless well within the boundaries of contemporary political correctness.

During the culture wars of the ’80s, Wojnarowicz was the frequent target of Republican outrage over publicly funded art exhibitions, much of it for his explicit and unapologetic gay sex imagery, much of it copied from pornography. As late as 2010, G. Wayne Clough, secretary of the Smithsonian, set off an international controversy when he removed a Wojnarowicz video from a National Portrait Gallery exhibition, after protests from the Catholic League and threats from Republican congressmen to reduce the Smithsonian’s funding.

The film Wojnarowicz: F**K YOU F*GGOT F**KER is a kind of side door to the artist’s life and career, and a surprisingly complete account of both. The subtitle (without the asterisks) is taken from the title of a large painting, based in turn on the caption to a crude homophobic cartoon Wojnarowicz found, like much of his material, in the street. The four words, described in the film as “so offensive,” set the tone for the whole.

Quite apart from its content, Wojnarowicz is an impressive piece of filmmaking. Besides being a painter, Wojnarowicz was a writer, author of several books, filmmaker, photographer, songwriter/recording artist (with a collaborative rock band called 3 Teens Kill 4), performance artist, and AIDS activist. His friends included filmmakers and photographers. Everything from this intimidating archive, including photographs, videos, audio journals, TV clips, drawings, paintings, performance tapes, news headlines, even, apparently, the artist’s answering machine cassettes, made its way into the film. Director Chris McKim blends in interviews with fellow East Village zeitgeist figures like photographer Nan Goldin, writer Fran Lebowitz, and artist Kiki Smith, along with his dealer and boyfriend. The film uses a polished version of the film collage fast-cutting techniques of ’60s underground experimental filmmakers like Kenneth Anger and Stan Brakhage. Unlike most Anger and Brakhage films, though, Wojnarowicz essentially takes the form of a chronological narrative. But it explodes into life with a relentless mix of sound, image, and text — moving just below the speed of thought and making use of Internet-trained synapses, capable of making connections and meaning at a breathtaking clip.

The wealth of source material means that Wojnarowicz’s face and voice fills the entire film; dead for nearly 30 years, he is the work’s inevitable and unavoidable star. In a short one hour and 48 minutes, the film manages to do, and do well, a surprising number of complicated things. There is the biography, from Wojnarowicz’s horrific childhood with an abusive, alcoholic father; a brief stay in an orphanage; teen years dividing his life between his mother’s tiny New York apartment and the streets, where he wandered and hustled sex for weeks at a time; his development and then sudden success as a young artist; the death of his mentor and friend Peter Hujar; and the relentless anguish of the early AIDS years, which end with his own death from the disease.

There is the social context: the rise of a new conservative movement during the Reagan years; the brief but epic era of the East Village art scene; the upswing of activism, especially over the Federal government’s stony indifference to AIDS. The film is subtle in making its political points, particularly around Wojnarowicz’s critique of “One Tribe” America — a politics in which groups that don’t fit the format are inevitably marginalized and persecuted. Donald Trump — then and now — appears briefly in several scenes, underscoring how tribal issues continue to roil American culture.

The stage is pre-Bloomberg New York City, with its trash-filled alleys, abandoned piers, post-industrial streets, and grubby artist lofts. The film is even good on the work itself and the mysterious inevitability of Wojnarowicz’s most arresting images, exploring how he mastered various graphic techniques, his blending of street styles, advertising and commercial graphics, and art world influences.

This is a film that covers a lot of dark and tragic territory: the abrupt decline of the East Gallery era that abruptly pushed Wojnarowicz’s art out of fashion and cut his sales even as the East Village galleries themselves were pushed out by gentrification; the creeping nightmare of AIDS; Hujar’s lingering death; and Wojnarowicz’s slow descent into dementia. Yet the film itself remains entertaining throughout, no doubt more than anything else from its skill in capturing the fierce, tender, acidic, brilliant, and ultimately inextinguishable energy of its subject.

Peter Walsh has worked as a staff member or consultant to such museums as the Harvard Art Museums, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Davis Museum at Wellesley College, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, and the Boston Athenaeum. As an art historian and media scholar, he has lectured in Boston, New York, Chicago, Toronto, San Francisco, London, and Milan, among other cities, and has presented papers at MIT eight times. He has published in American and European newspapers, journals, and in anthologies. In recent years, he began a career as an actor and has since worked on more than 80 projects, including theater, national television, and such award-winning films as Spotlight, The Second Life, and Brute Sanity. He is a graduate of Oberlin College and Harvard University.

Wonderful review. I started looking at DW’s photographs in college, particularly the One Day… and the Rimbaud series had a big effect on me, having had very little understanding of his subject matter.

Where is this streaming?

I will tell you when I know — I asked the publicist about how (and when) people can screen this and have yet to get a response.

Here you go — through November 19 at the DOC NYC site — Link

Glad to hear it, I’m looking forward to watching it