Classical CD Reviews: Michael Daugherty’s “This Land Sings,” Ethel Smyth’s “The Prison,” and David Lang’s “prisoner of the state”

By Jonathan Blumhofer

A welcome political homage to Woody Guthrie; a new recording of Ethel Smyth’s 1931 choral symphony makes a strong case for a full reconsideration of her output; and David Lang’s rejiggering of Beethoven’s Fidelio is both stirring and timeless.

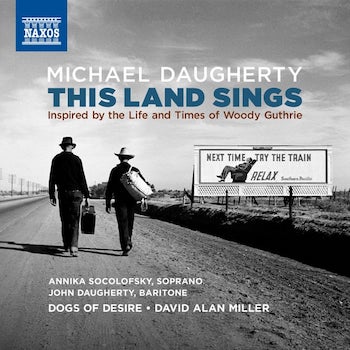

Woody Guthrie seems a natural subject for theatrical treatment. The question is: how does one do him any justice? To some degree, his songs define 20th-century American folk music. His life, full of ups and downs, ended in tragedy and, yet, there’s something profoundly triumphant about his story. Leave it to Michael Daugherty – whose previous works have mined American popular culture from Superman to Jackie O. – to try and make sense of Guthrie’s life in memorable, unaffected, and, ultimately, touching fashion.

This Land Sings, his 2016 homage to the mid-20th-century bard, doesn’t lack for verve. Using snatches of Guthrie’s songs and lyrics, plus plenty of his own texts, Daugherty weaves a tribute to Guthrie that’s both poignant and auspicious. “Hot Air,” a sardonic satire of right-wing radio, draws easy parallels between the likes of Rush Limbaugh and Charles Coughlin. “Silver Bullet” bitingly equates war and domestic violence. Meanwhile, “Bread and Roses” celebrates the women’s suffrage movement.

Throughout, Daugherty’s text settings are utterly fresh: there’s a constant sense of variation to be heard in This Land’s 17 tracks. The music hardly repeats itself (even on the verses of the songs). Indeed, Daugherty’s compositional facility is on wonderful display throughout: every bar feels stylistically, expressively, and/or musically assured. Throw in some subtle connections between themes and motives and you’ve got a piece that is winningly structured (not to mention dramatically tight).

The performance, featuring soprano Annika Socolofsky, baritone John Daugherty (no relation to the composer), and Dogs of Desire (led by David Alan Miller), is bracing. The ensemble certainly digs Daugherty’s digressions into vernacular musical forms. “Marfa Lights,” the fourth-movement instrumental episode, is suitably soulful, with a kind of gritty flugelhorn solo. “Mermaid Avenue” brims with klezmer spirit. And the accompaniment to “Graceland” is kinetically Elvis-ish.

Socolofsky and Daugherty acquit themselves perfectly well on their solo numbers but have a striking rapport in their duets. There’s an easy bounce in the dialogue between the singers in “Don’t Sing Me a Love Song” and the concluding “Wayfairing Stranger/900 Miles” proves particularly affecting (with one singer singing and the other whistling a haunting descant).

The whole This Land Sings, then, with its highly idiomatic scoring, vocal writing, and inventive spirit, is a decided winner in its debut recording. To be sure, the piece has an edge – Daugherty’s left-leaning political views don’t hide too far beneath its surface – but everything ties together in a tribute to the moral clarity of so much of Guthrie’s work. A welcome, important, political essay, this – and coming not a moment too soon.

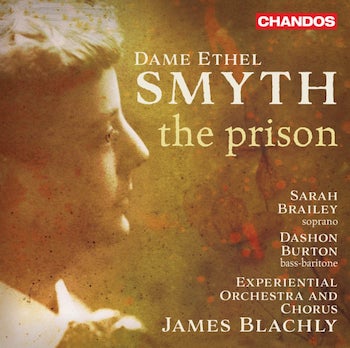

Amid a general reckoning these past few years with the absence of music by women composers in the canon, Ethel Symth’s name has been something of a constant. Granted, she seems to have been little more than a fringe figure since her death in 1944. Lately, though, the tide appears to be changing, and a new recording of The Prison, her 1931 choral symphony, makes a strong case for a full reconsideration of her output.

Amid a general reckoning these past few years with the absence of music by women composers in the canon, Ethel Symth’s name has been something of a constant. Granted, she seems to have been little more than a fringe figure since her death in 1944. Lately, though, the tide appears to be changing, and a new recording of The Prison, her 1931 choral symphony, makes a strong case for a full reconsideration of her output.

In The Prison, Smyth set a sometimes dense and stiff libretto by her friend Henry Bennett Brewster, which follows the meditation of a wrongly condemned prisoner the night before his execution. In its metaphysical tone, The Prison sounds a bit like a distant relative of Elgar’s The Dream of Gerontius, though it inhabits its own musical world.

Indeed, Smyth’s writing is often sumptuous and lyrical. In The Prison’s first part there are some conspicuously fine evocations of the natural world, as well as an orchestral “Dawn Interlude” that, while far more Romantic in aspect, bracingly anticipates Britten’s Peter Grimes by about 15 years. One of the highlights of Part Two is an enchanting recreation of an Ancient Greek chorus (“The laughter we have laughed”) Smyth copied on a trip to Smyrna.

Overall, the score is full of striking gestures – the spare, mysterious opening of Part 1; a beguiling final chord at that part’s end (anchored by violins and violas playing artificial harmonics) – idiomatic vocal writing for soloists and choir, and touching effects (e.g., “The Last Post” sounding after the Prisoner’s execution).

Chandos’s recording, which features the soprano Sarah Brailey, bass-baritone Dashon Burton, and the Experiential Orchestra and Chorus led by James Blachly, seems perfectly at home in all of it. The solo singing is flawless: Burton’s Prisoner is fervently and sympathetically done; Brailey’s account of the Prisoner’s Soul floats with effortless radiance.

One might ask for occasional bolder contrasts of gesture and dynamics from the choir and orchestra – there’s a feeling of holding back for the sake of balance in some of the climactic passages – but the ensembles have the feel of Smyth’s style well in hand. The choral singing is uniformly warm and in tune while the orchestra revels in the shifting colors of Smyth’s instrumentation. In all, a captivating piece, belatedly (just before its 90th birthday!) done justice.

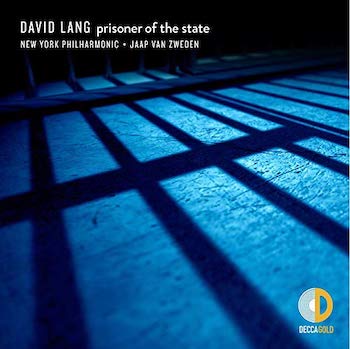

Just as Smyth’s Prisoner was unjustly damned (for a crime not specified in the libretto), so is the unnamed title character of David Lang’s prisoner of the state. A reworking of Beethoven’s Fidelio, this taut, one-act opera is out now in its gripping debut recording from the New York Philharmonic (NYPO) and music director Jaap van Zweden.

Just as Smyth’s Prisoner was unjustly damned (for a crime not specified in the libretto), so is the unnamed title character of David Lang’s prisoner of the state. A reworking of Beethoven’s Fidelio, this taut, one-act opera is out now in its gripping debut recording from the New York Philharmonic (NYPO) and music director Jaap van Zweden.

In his reworking of Beethoven’s flawed masterpiece, Lang doesn’t really do away with one of Fidelio’s biggest problems: everybody’s still basically a cardboard cutout. But Lang uses this fact to his advantage. prisoner of the state doesn’t waste your time or overstay its welcome.

That’s partly because it’s dramatically riveting. Beyond the frequent spare presentations of its textures and motives, there are episodes of harrowing intensity (“prisoners! wake up!”), powerful juxtapositions of different types of musical projection (the partly-sung, partly-chanted, partly-shouted “prison song”), and catching allusions to archaic forms (the proto-chaconne during the “entrance of the governor”) to be found among the score’s pages.

This mostly compensates for the prisoner’s one musical flaw, namely an overabundance of slow and moderate tempos. Simply put, there’s too little fast music to provide contrast or relief, though the sheer amount of variation of themes and motives in Lang’s writing does keep tedium from setting in.

Regardless, one could hardly ask for a finer performance of a major new work. Julie Mathevet’s Assistant ably balances the part’s demands for steely courage and vulnerability. Eric Owens’s blustery Jailer is suitably villainous to start but warms as the character begins to find some kernel of a conscience. Alan Oke’s Governor is chilling throughout, while Jarrett Ott brings a purity of tone to the Prisoner (who, unlike in the Smyth, here survives his circumstances).

The Men of the Concert Chorale of New York sing with energy and supple tone, especially in the second prisoners’ chorus (the compelling “o what desire”).

I remain convinced that, given the right conductor and circumstances, even the most traditional orchestras can bring new music as thrillingly to life as they can Beethoven. This album only reinforces that belief. Van Zweden draws playing of crackling rhythmic vitality from the NYPO; as a result, Lang’s music dances like you’ve probably never heard it do before.

Grim though its moral may be (essentially: everybody’s a prisoner in some way, though not all are in chains), prisoner of the state makes for theater both stirring and timeless. In the midst of all the day’s uncertainty, this is a potent, welcome release. Don’t miss it.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Chandos, David Lang, Decca Gold, Ethel Smyth, Michael Daugherty, Naxos, The Prison, prisoner of the state