Book Review: Filmmaker Werner Herzog — On the Hunt for the Ecstatic Truth

By Tim Jackson

This thoughtful study offers a worthwhile critical perspective on Werner Herzog, one of the world’s great living film artists.

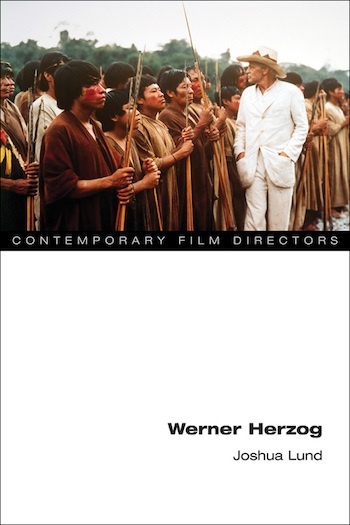

Werner Herzog by Joshua Lund. University of Illinois Press, 288 pages, $22 (paper).

Click here to buy.

Joshua Lund’s Werner Herzog begins and ends with a comment the director made after his interview with convicted murderer Linda Carty for his 2011 mini-series, On Death Row. “I have to make one remark, ” Herzog insists, “I do not humanize her. I do not make an attempt to humanize her. She is simply a human being. Period.”

Joshua Lund’s Werner Herzog begins and ends with a comment the director made after his interview with convicted murderer Linda Carty for his 2011 mini-series, On Death Row. “I have to make one remark, ” Herzog insists, “I do not humanize her. I do not make an attempt to humanize her. She is simply a human being. Period.”

The sentiment is well chosen: it articulates what lies at the heart of the imagination of one of the world’s great living film artists. His films, historical and contemporary, documentary and narrative, serve one essential intention: to ennoble unheralded, eccentric characters. The challenge to do this becomes part of the director’s creative process: Herzog’s productions often require that he, his actors and crew subject themselves to physical challenges in exotic locations or work with non-professional actors and native populations. Herzog’s goal is to discover what he has famously called an “ecstatic truth.” What does that mean to the director? “Filmmaking is more athletics than art and filmmaking comes from the thighs.”

Lund fully inspects Herzog’s body of work — thighs and all. Along with looks at the director’s books, scripts, and interviews, he takes special pains to place the moviemaker’s early films in a broad political context. Herzog denies having an ideological perspective, but Lund undercuts this claim with a clear analysis of the historical and cultural context that generated Herzog’s stories and characters. He places Herzog in the German Romantic tradition, in the category that he calls the “sublime”: in all things there are extremes of both pleasure and pain. These clashing polarities threaten to overwhelm the imagination, but they can be subdued by reason. In film, an idea or a beautiful image inevitably embraces and repels its opposite. Thus Lund sees Herzog’s films as juggling “life affirming and crisis provoking tendencies.” The need to create order from the ‘disorder of real life’ shape the stories Herzog tells as well as his methods of production.

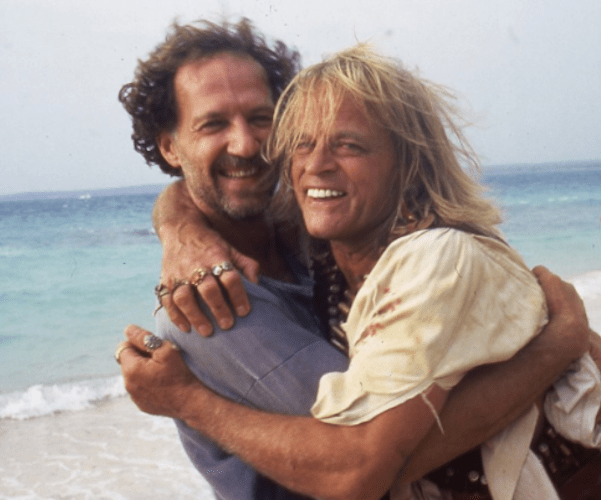

Three of Herzog’s best known early films — Aguirre:Wrath of God (1972), Fitzcarraldo (1982), and Cobra Verde (1987) — starred Klaus Kinski and the projects were significant challenges, to put it mildly. The first two films were shot in the Amazon and the experiences so daunted Herzog that he found the productions and location to be bewitched: “We are cursed. It’s a land where God, if he existed, had created in anger.” Cobra Verde is based on the controversial life of Francisco Félix de Sousa, a successful West African slave trader in the early 1800’s. In the process of attempting to re-create the historical background, Herzog employed hundreds of natives as actors; he secured authentic costumes and scouted out locations. Meanwhile, his lead, Kinski, was careening toward madness. Their relationship (documented in Herzog’s 1999 film My Best Fiend) was volatile to the point of bordering on the lethal. Yet Herzog continues to admire the actor’s screen charisma and his willingness, like Herzog, to commit to a production totally. Kinski, however, became increasingly unhinged — performances needed to be coaxed out of him. The final results — despite or because of the battles — are mesmerizing. For a young Herzog, films required fortitude and determination: not only when it came to researching and scripting his difficult subjects, but the need to improvise when it came to the daily operations of his crews and set-ups for locations. He became an expert at a kind of guerilla filmmaking.

“Simply, I do not care about themes, I care about stories,” proclaims Herzog. His protagonists, he explains, are “solitary rebels with no language to communicate.” In examining the director’s work, Lund expands well beyond this emphasis on story and character, plugging them into their broader sociopolitical contexts. In Aguirre: Wrath of God, loosely based on the life of the crazed 16th century Spanish explorer of the Amazon, “Herzog and Kinski plant fleeting images of man’s distress before a world he has created.” Aguirre and Fitzcarraldo are more than fables about men doomed by hubris and twisted ambitions — they are scathing critiques of capitalist exploitation. The settings of the films evolve into dreamscapes in which the natural world manifests “physical signs of the unconscious … nightmares against which Herzog’s protagonists consistently struggle and that permeate the border between the stories’ world and the story of the making of that world.” The “ecstatic truth” lies in the “portraits of those on the losing end of history [who] are full of pathos, ecstasy, and exhilaration.”

Director Werner Herzog — then and now.

That description carries forward to both his documentary and narrative films about America and “the eccentricities of American capitalism.” In Enigma of Kasper Hauser (1974) and Stroszek (1977), Herzog shifts from a focus on outer landscapes to “inner landscapes.” Skepticism about both the dehumanization of modernism and the constraints of traditional society are prominent. Bruno S. (real name Schleinstein), the protagonist of both films, was institutionalized in his youth. He became a street musician and, following an appearance in an experimental 1971 documentary, was discovered by Herzog. Aside from that documentary, Bruno had never appeared on screen before. But that amateurishness becomes his strength, at least in Herzog’s world. Bruno’s insecurity and vulnerability, his quirky physicality and resilience, suit the director’s vision of people who are defeated by history. Kasper Hauser is a re-imagining of a real life historical figure who claimed he was raised in a cell. He was discovered at around the age of 16, taught to speak, and groomed back into becoming part of society. Lund describes the figure’s attraction to Herzog: “We are invited into the world of an individual literally as a blank slate.” In Stroszek, Bruno gets deep into his role as a hapless, not-too-bright pimp and dreamer who escapes Germany. He arrives in America with a prostitute named Eva (Fassbinder actress and Herzog’s former partner Eva Mattes). Eventually, they find themselves attempting to put down roots in Plainfield, Wisconsin. But the land of opportunity, where they hope to find “freedom from state power,” soon turns into a fool’s errand in the land of dog-eat-dog. The film’s initial dark humor slowly grows tragic.

Herzog’s fascination and admiration for seekers, dreamers, and mad men extends to his prolific documentary work. Some examples would include How Much Wood Would a Woodchuck Chuck (1976),which studies American auctioneers; La Soufrière (1977), which is set before the imminent eruption of a volcano on the island of Guadeloupe; The Great Ecstasy of Woodcarver Steiner (1974), the profile of a champion ski jumper who is also a woodcutter; God’s Angry Man (1981), a short film about Gene Scott, a wealthy and charismatic television pastor. Herzog’s more recent documentaries, which draw on interviews and the director’s narration, continue to approach their subjects with respect and open-minded curiosity. One standout effort: 2005’s Grizzly Man, in which Herzog makes compelling use of footage shot by Timothy Treadwell, an eccentric eco-warrior who spent 13 years living with Alaskan Grizzlies. The director fashions a nature-based variation on the Icarus myth. The key to the film’s charm: Herzog’s colorful commentary, which is delivered in his dry Bavarian accent. Another favorite: 2011’s Into the Abyss, in which murderers on death row are allowed to speak as human beings, despite their unspeakable crimes.

Werner Herzog and Klaus Kinski — sharing a happy moment.

Late in the book, Lund touches on Herzog’s more recent narrative films, which are often cast with actors who are skilled in giving nail-biting performances: Rescue Dawn (2006) with Christian Bale is based on the story in Herzog’s documentary Little Dieter Needs to Fly (1997); Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans (2009) features Nicolas Cage,is a surreal remake of the gonzo Abel Ferreira film of from 1992. Lund also offers some acute observations on Herzog’s appearances as an actor. As the book was going to press, Herzog was finishing 2019’s Family Romance, LLC, a blend of documentary and narrative that premiered this April on the streaming service Mubi. (Arts Fuse review) His latest, Nomad: In the Footsteps of Bruce Chatwin, is a profile of his long relationship with the celebrated travel author whose book The Viceroy of Ouidah was the basis for Herzog’s Cobra Verde. (Nomad is currently screening virtually at the Coolidge Corner Theater.)

Herzog, like the subjects of his best films, is a seeker. The range and variety of his film work is vast; for decades he has been concerned with nothing less than the price of civilization and how it shapes the soul of man. Lund admits that, throughout his career, the director has been nothing if not elusive about criticism of his vision: “from the formative moments of crafting his persona . . . [he] always resists and even denounces too much analytical probing into his work.” Still, this thoughtful study offers a worthwhile perspective on Herzog’s impressive achievement.

Tim Jackson was an assistant professor of Digital Film and Video for 20 years. His music career in Boston began in the 1970s and includes some 20 groups, recordings, national and international tours, and contributions to film soundtracks. He studied theater and English as an undergraduate, and has also has worked helter skelter as an actor and member of SAG and AFTRA since the 1980s. He has directed three feature documentaries: Chaos and Order: Making American Theater about the American Repertory Theater; Radical Jesters, which profiles the practices of 11 interventionist artists and agit-prop performance groups; When Things Go Wrong: The Robin Lane Story, and the short film The American Gurner. He is a member of the Boston Society of Film Critics. You can read more of his work on his blog.