Book Review: “Beneficence” – A Family, A Farm, An Unshakable Feeling

By Melissa Rodman

Beneficence is a novel that lingers, tucking details into its heavy folds.

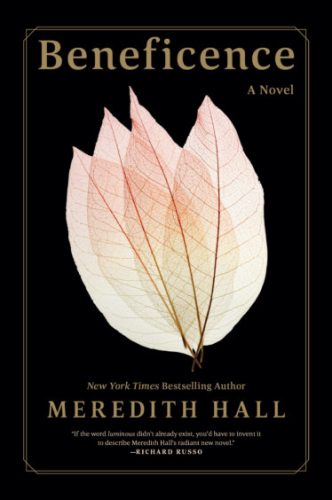

Beneficence by Meredith Hall. Godine, 296 pages, $25.95.

Embedded in the heart of Meredith Hall’s 2007 bestselling debut memoir, Without a Map — and its subconscious throb — are these lines by poet Charles Simic: “I am in dialogue with certain elements of my life… My effort to understand is a perpetual circling around a few obsessive images.” For Hall, the dialogue and the images it generates revolve around becoming pregnant at sixteen and giving up her baby for adoption. Memoir, yes, concerns a writer’s sense-making and sense-of-self-making, her grappling with and framing a specific slice of life. “I circle my own obsessive images, examining each small fragment in the light, laying one against the next until the image becomes memory,” Hall acknowledges, in conversation with the Simic quotation. Now, thirteen years later, Hall’s circling has steered her to a first novel, Beneficence, and the weight of ache and grace that anchors her writing is still firmly lodged, channeled through new characters and their stories.

The aptly named Senters are the fictional family at the center of Beneficence, which traces their life on a farm in Maine from 1947 to 1965 in chapters written through the interchanging eyes of father Tup, mother Doris, and daughter Dodie. In addition to middle child Dodie, Tup and Doris have sons — eldest child Sonny and youngest child Beston — and the book opens by detailing their largely tranquil, idealized bubble of hard work, followed by rest and gratitude at day’s end. Even in the first section, though, our antennae are raised by intimations of trouble; the section is entitled “Before,” a harbinger of something about to happen. “We can’t ever know what will come,” Doris forebodes.

What comes — Sonny is killed accidentally while the children and two friends are playing with an old gun — hits with a reverberating boom. Sonny’s death shatters the Senters, and the rest of the novel dwells in the space carved out for Tup, Doris, Dodie, and Beston. The bullet, that fundamental pang and loss, spreads in a multifaceted haze. Doris drifts away from her family and into her head; Tup takes an extra job in town and slips into a partial second life and family there; and Dodie is left to pick up the slack, both around the farm and in feeling responsible for Beston. Throughout, the Senters ruminate on the past, present, and the possibility of recuperating as a family, holding “each small fragment in the light,” per Hall’s meditations in Without a Map.

Sonny’s death defines the novel’s timeline — the “Before” section is followed by “During,” “After,” and “Here” — but the characters’ memories spill around those markers. Sonny’s painstakingly curated specimen collection from “Before,” for instance, gathers dust “After.” Dodie’s high school valedictory speech “After” excerpts a motto, Dum spiro, spero (While I breathe, I hope), that Tup taught the three siblings way “Before.” These details, and others, are tucked deep in Beneficence’s heavy folds. It is a book that lingers and does not read in a single gulp.

Hall’s fascination with memory, as well as with particular imagery, has persisted across genres, starting with her 2005 New York Times “Modern Love” column, which grew into Without a Map, and now into Beneficence. Indeed, the novel’s characters struggle with feelings and act out scenes that overlap with Hall’s own story of having a son at sixteen (in Beneficence, Doris has Sonny at nineteen) and losing that child (not only Sonny but also a daughter Tup conceives and leaves, a noncommittal offshoot of his second life). There is also the process of bringing the strands of a family back together, among other autobiographical resonances. “There were no patterns for how to do this, how to hold each other safely and fully after a lifetime apart. We could not plot out the future,” Hall concludes in her column/memoir, “We were a family. We loved each other. We needed each other. That was our only map.” These words are now Tup’s in Beneficence: “It would be comforting to have a guide to follow. I have none… Every family makes up its own rules… There is no map.” Beneficence is cloaked as fiction, but underneath it is an iteration of real-life, unshakable feelings and “obsessive images.”

Melissa Rodman writes on the arts, and her work has appeared in Public Books and The Harvard Crimson among others.