Book Review: “The Atomic Bomb on My Back” — Witness to Apocalypse

By Robert Israel

Reading Sumiteru Taniguchi’s book brought back my memories of meeting a man who had seen the unimaginable.

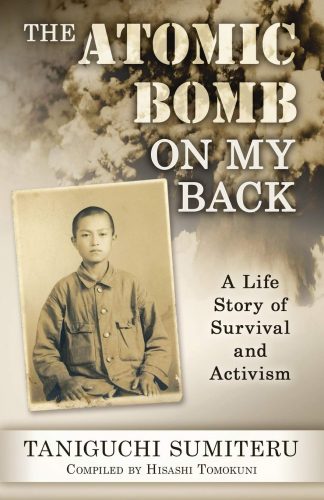

The Atomic Bomb on My Back: A Life Story of Survival and Activism by Sumiteru Taniguchi. Compiled by Hisashi Tomokuni. Rootstock Publishing, Montpelier, Vermont.

The 75th anniversary of the dropping of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bombs – observed on August 6 and 9 this year — is fraught with portents. We live in a nation that possesses a stockpile of these weapons; our President, an atomic weapons proponent, this year warned he might use them in confronting bellicose threats from North Korea and Iran, two “rogue” nations who have defied economic sanctions in vigorous pursuit of acquiring their own atomic weapons arsenals. And, while it’s true that these weapons haven’t been deployed since 1945, the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists point to them as one of the elemental dual threats facing our planet – the other is climate erosion — forcing the organization to advance the hands of the Doomsday Clock forward to 100 seconds to midnight.

The 75th anniversary of the dropping of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bombs – observed on August 6 and 9 this year — is fraught with portents. We live in a nation that possesses a stockpile of these weapons; our President, an atomic weapons proponent, this year warned he might use them in confronting bellicose threats from North Korea and Iran, two “rogue” nations who have defied economic sanctions in vigorous pursuit of acquiring their own atomic weapons arsenals. And, while it’s true that these weapons haven’t been deployed since 1945, the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists point to them as one of the elemental dual threats facing our planet – the other is climate erosion — forcing the organization to advance the hands of the Doomsday Clock forward to 100 seconds to midnight.

When we cast a backward glance on this ominous anniversary, we tend to limit our view to taking stock of its deadly toll: a combined estimate of 180,000 Japanese men, women, and children were incinerated, along with their cities, moments after the blasts. The bombs put an end to World War II and enabled American troops to return home – my father, an Army officer stationed in Asia in 1945, was one of those men who returned. This makes the anniversary a personal story, not only for families like mine, but for those individuals who miraculously survived – many of them children or teenagers at the time — known in Japanese as hibakusha. And it also serves as an opportunity to memorialize the souls of those who lost their lives.

As a reporter in Japan in the late ’80s, I interviewed a number of hibakusha for stories that were later published in the Montreal Gazette. Among the men and women I met was writer and activist Sumiteru Taniguchi, who died at age 88 in 2017. His book, The Atomic Bomb on My Back, originally published in Japanese in 2014, has recently been translated into English, and it will be released on Nagasaki Day — August 9.

When I met Taniguchi in Nagasaki in 1987, he was guest speaker at a middle school assembly. He told the youngsters – who had placed garlands of multicolored paper origami cranes, the symbol of the hibakusha peace effort, on the school cafeteria’s floor – that he had not been much older than them when the atomic bomb fell on his hometown.

“I was a postal delivery boy,” he tells the youngsters in a story recounted in his book, “riding my bike to deliver the mail to my neighbors when the bomb fell. When I awoke, the letters in my postal bag was swirling all around me, and I attempted to gather them up. That’s when I collapsed. The skin of my left arm, from the shoulder to the tip of my fingers, was burned and trailing like a rag. Bodies, burned black, voices calling for help from collapsed buildings, people with flesh falling off. This place became a sea of fire. It was hell.”

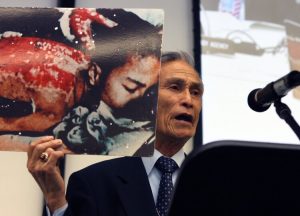

Taniguchi holding a picture of his burns at the 2010 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty Review Conference. Photo: Rootstock Publishing.

Taniguchi describes the numerous operations he endured in order to have his wounds treated. He was finally discharged from the hospital in 1949. But, he writes in The Atomic Bomb on My Back, he never experienced enduring relief; he needed to return for treatments dozens of times to remove lumps that kept forming in his back.

He also writes painfully of the social stigma he endured as a survivor, of his marriage to his wife Eiko 10 days after meeting her, and of his anxiety at showing her his scars on their honeymoon, fearful that she would reject him.

When I heard Taniguchi speak to the youngsters in Nagasaki, he said he did not want to have to tell these stories. He insisted he was a private man who did not want to share his agonies. He preferred to have lived his life apart from others. But when a photo of his “reddened back” appeared in public, he joined the Japanese antinuclear movement. As detailed in his book, he made numerous public appearances at rallies. He wanted to reach young people, he said, because he believed they would be the ones to continue the necessary political work begun by the hibakusha, who are now elderly and frail.

Reading Taniguchi’s book brought back the memories of meeting a man who had seen the unimaginable. He had walked away from a hellish maelstrom and lived to tell about it. A thin, haunted man, his speech was labored as he tried to draw breath to form sentences. His book captures his halting, labored efforts to articulate what he had seen. I liken him to the Ancient Mariner from Coleridge’s poem, compelled to share his horrific story, who passed “like night, from land to land” with “strange power of speech.”

Taniguchi, at the time of his death, was under consideration to receive the Nobel Peace Prize. In The Atomic Bomb on My Back he has left us disturbing eyewitness testimony as well as a moving call to action. The book comes, like the anniversary, at a propitious time. We are not only collectively struggling to emerge from a pandemic, but to confront the sins of American history. The terrible legacy of Hiroshima and Nagasaki — our unwillingness, to this day, to face the truth behind the mass killing of civilians — must be part of our moral reckoning with our past, if only to create a safer future.

Note on the author: Taniguchi Sumiteru was a survivor (hibakusha) of the 1945 atomic bombing of Nagasaki, a prominent activist for a treaty prohibiting nuclear weapons, chairman of the Nagasaki Council of A-Bomb Survivors, and co-chairperson of the Japan Confederation of A-and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo). He devoted his life to informing people of the consequences of the 1945 atomic bombing and campaigning for the abolition of nuclear weapons, making frequent public appearances to speak to student groups and participate in demonstrations calling for nuclear disarmament around the world. Taniguchi-san was an initial proposer of the Hibakusha Appeal, an international signature campaign for the elimination of nuclear weapons that is now supported by the Union of Concerned Scientists and many US and international peace organizations, including the IPB and the ICAN. He died in 2017.

Robert Israel, an Arts Fuse contributor since 2013, can be reached at risrael_97@yahoo.com.

This anniversary should also send people to Robert Jay Lifton and Greg Michell’s indispensable 1995 book Hiroshima in America: Fifty Years of Denial. It is now 75 years of determined forgetting. In terms of history, the study takes a scathing, meticulously factual look at the obfuscation and repression that has driven the dominance of the ‘official story,” which rationalizes the dropping of the bombs. It also chronicles the years of cover-up, culminating in the debacle of the Smithsonian Institution’s botched (and censored) attempt to deal with the human effects of the bombing in its exhibit on the 50 anniversary of Hiroshima. Nothing had been scheduled at the Smithsonian this year to commemorate the anniversary. (In March, the LA Museum had put on the exhibit Under a Mushroom Cloud: Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and the Atomic Bomb. The show is the result of a collaboration between the Japanese American National Museum and Hiroshima Peace Museum in Japan. The JAMN is planning to extend “Under a Mushroom Cloud when the museum reopens to the public. It will provide a new closing date once it has been determined.”)

Significantly for today, Hiroshima in America backs up its first sentence: “You cannot understand the 20th century without Hiroshima.” Why? “”Hiroshima signified the pointless apocalypse — the sudden realization that we could extinguish ourselves as a species, with our own technology, by our own hand, and to no purpose. ”

The book’s look at the resonance of that vision — culturally, psychologically, and morally — makes it particularly relevant now. Our continued acceptance of “Hiroshima distortions was bound to have its effects on the America psyche and American history … the cumulative influence of Hiroshima turns out to be much greater than most Americans suspect. Indeed, one may speak of the bomb’s contamination not only of Japanese victims and survivors, but of the American mind as well. But that very contamination — the aberrations in American life induced by Hiroshima — if confronted, can become a source of renewal.”

The connections with the Climate Crisis are obvious — our love/hate of the apocalyptic, the commitment to denial rather than confrontation — and are examined by Lifton in another invaluable book, The Climate Swerve: Reflections on Mind, Hope, and Survival.

I would also recommend readers turn to Japanese author Kenzaburo Oe — the Nobel literature laureate — whose book Hiroshima Notes remains, many years later, a must-read.

Here’s a quote from that book:

“In the broadest context of human life and death, those of us who happened to escape the atomic holocaust must see Hiroshima as part of all Japan, and as part of all of the world. “

An excellent suggestion, the Oe. Also, I would like to add to this list Robert Jay Lifton’s Death in Life: Survivors of Hiroshima, a magisterial study of the psychological effects of the bomb on 90,000 survivors.