Film Review: CREEM on Top — The Story of America’s Only Rock ‘n’ Roll Magazine

By David Stewart

The documentary is about “the power of the community and how rock and roll, and music in general, is worth fighting for: sometimes that means doing it yourself.”

A broken typewriter sits on a pedestal like a hunting trophy as plumes of marijuana smoke waft through the air. Mitch Ryder is jamming so loud that a poster of Mick Jagger hanging on the wall starts to shimmy and shake. Meanwhile, writers are entering into heated debates with other writers over The Stooges versus whatever is being piped through the transistor radios of Detroit. For outsiders, the place looks and sounds like a college frat house fit for Animal House. To those inside the office, it’s just another day at CREEM magazine.

A broken typewriter sits on a pedestal like a hunting trophy as plumes of marijuana smoke waft through the air. Mitch Ryder is jamming so loud that a poster of Mick Jagger hanging on the wall starts to shimmy and shake. Meanwhile, writers are entering into heated debates with other writers over The Stooges versus whatever is being piped through the transistor radios of Detroit. For outsiders, the place looks and sounds like a college frat house fit for Animal House. To those inside the office, it’s just another day at CREEM magazine.

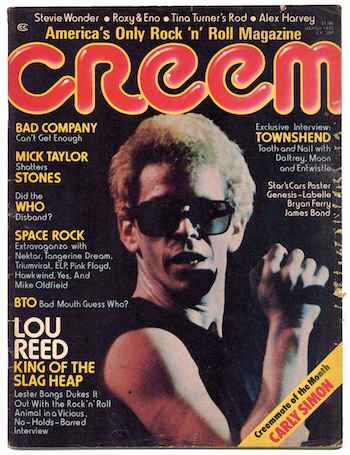

Scott Crawford’s long-awaited documentary CREEM: America’s Only Rock ‘n’ Roll Magazine (arriving in theaters and virtual cinema on Aug. 7) focuses on the rise, fall, and legacy of the celebrated Detroit-based publication. From 1969 to 1989, CREEM rivaled Rolling Stone as one of America’s premier rock and roll magazines. Under the patriarchal guidance of publisher Barry Kramer there was gathered together a cadre of misfit writers and ex-class clowns who would ultimately break iconoclastic ground in rock journalism. From the unfiltered, stream-of-consciousness prose of Lester Bangs — a critic immortalized by Philip Seymour Hoffman in the film Almost Famous — to Patti Smith’s articles before she revolutionized punk rock, CREEM was an anarchistic community magazine energized by writers, musicians, and fans joined at the hip.

Crawford, who covered the ’80s DC punk scene in the fan-run outlet Metrozine and his 2014 film Salad Days, has a personal connection to CREEM, “What we’re talking about here is a community,” says Crawford from his home outside of Washington. “The people who read the magazine, the people that wrote for the magazine, even the artists themselves, that’s what I loved about the story.”

Barry Kramer died in 1981 and he left the publication to his wife and son, JJ, to run. CREEM filed for bankruptcy in 1989. “From a personal perspective,” JJ says from his home in Columbus, OH, “it’s been four years and a lifetime in the making.” An intellectual property lawyer who is producing the film, Kramer wasn’t interested in a clean-cut retrospective about CREEM. Crawford says that “to JJ’s credit, he said, ‘Nothing is off-limits. Nothing!’” The DIY, punk-rock attitude that fueled the writers and readers was far from tidy.

After a successful Kickstarter campaign launched in 2016, Kramer and Crawford spent the next four years working to put together the story of CREEM magazine and its cultural impact on musicians and readers alike. In the film, R.E.M. frontman Michael Stipe and Chad Smith of the Red Hot Chili Peppers reflect on the magazine as a literary sanctuary that would, ultimately, shape their respective destinies. But the documentary is far from a hagiography: Joan Jett reads on camera her published retort to Rick Johnson after he panned the first Runaways album. According to JJ, “The relationship between the writers, the artists, and the fans were incredible; you could see how passionate the fans were and they would directly engage with the writers and sometimes the artists would directly engage through the letters section with the writers. CREEM would fire back and the artists would fire back and it’s a beautiful thing about the magazine.”

CREEM not only pushed taboos via its titillating content but also broke the glass ceiling with a roster of female contributors, a rarity in ’70s rock journalism, which was primarily a boy’s club. JJ says with satisfaction, “We were really happy that came into view as we were making the movie; the importance of the women of CREEM. Jaan Uhelszki (Former Senior Editor) said that she was responsible for writing a good deal of those snarky captions that you would see in the magazine. (Former Editor) Sue Whitall, along with contributors Sylvie Simmons and Patti Smith, wrote pieces for CREEM back in the day. Photographers like Lynn Goldsmith. So, they were a very early champion of pioneering female journalists. I think that could be its own story down the road on the influence of women at CREEM. They very much paved the way for future generations.”

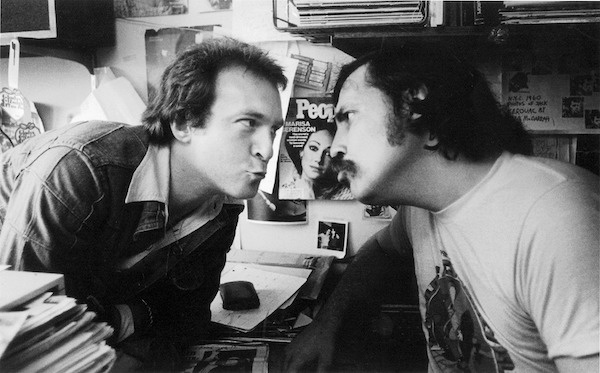

Lester Bangs (right) at loggerheads with CREEM‘s founder, Barry Kramer, in the magazine’s office in June 1974

The digital age and social media have since interrupted the communal connection between the writers, artists, and fans, which Crawford laments. Still, he admits the trend arguably stems from CREEM’s heyday. “I think that if you look online and spend more than five minutes on Twitter,” Crawford explains, “the snark factor and the fact that everyone’s a critic these days, I think you can connect the dots back to CREEM. No one was snarky back then, you know? No one was kind of bratty, except for CREEM, and they really created something very much their own and I think that there weren’t any other magazines that did that in the years to follow.” For Kramer, digital musical journalism has softened considerably since CREEM’s demise: “I think that there’s been a lot of homogenization, and a sort of sterilization in music media, which speaks to the point that CREEM is sorely missed as that kind of irreverent voice.”

However, the documentary has prompted Kramer to attempt to resurrect his father’s legacy by bringing CREEM back to its readers. “My dad left CREEM to me when he died, I was four-and-a-half years old, my mom stepped in as publisher and the plan was that she was going to keep it afloat until I was at an age to take over. Unfortunately, that didn’t happen. The magazine went into bankruptcy and was sold off.” Serendipitously, Kramer’s skills as an intellectual property attorney came in handy when it came to determining rights to CREEM material. “There were fragments out there – different folks with different claims to different pieces of the CREEM puzzle — and it took me 12-15 years to put all that back together.”

Plans for a commemorative edition of CREEM are in the works, along with an effort to resurrect the magazine on the web. Kramer notes that “we’re already talking about what happens after that in terms of our online presence and, hopefully, additional quarterly publications as well. As digital as the world is right now, there’s something really special about being able to touch the pages. I think the world needs CREEM now more than ever so I would love to help be a part of bringing it back.”

When asked about what they hope will stay with viewers after seeing the documentary, Crawford says that “One of the things that attracted me to this story was a similar theme in the film Salad Days. The power of the community and how rock and roll, and music in general, is worth fighting for: sometimes that means doing it yourself.” As for JJ, “I hope audiences will be inspired by CREEM’s DIY spirit. If you take a step back and look at this group of outliers and misfits that had no business writing or running a rock and roll magazine and it went from being an underground newspaper to becoming a regional tastemaker and then elevated into a national powerhouse. That’s an incredible testament to rolling up your sleeves and doing things on your own terms. Especially doing it in Detroit, of all places!”

David Stewart is a Professor of Film and Media Studies at Plymouth State University. Along with teaching, he is a documentary researcher and contributing writer for PleaseKillMe.com and DMovies.org. His film credits include Amy Scott’s documentary Hal and Marielle Heller’s The Diary of a Teenage Girl. He lives outside of Boston with his family and beloved Fender acoustic, Nadine.

Speaking of loggerheads, it looks to me like Lester B is the guy on the right.

You are right — fixed. Thanks … got my loggerheads confused.