Opera Album Review: Is Perfection Still Possible? Lully’s “Isis” under Christophe Rousset

By Ralph P. Locke

Is it any wonder? An opera that angered Louis XIV in 1677 brings enormous pleasure in 2020.

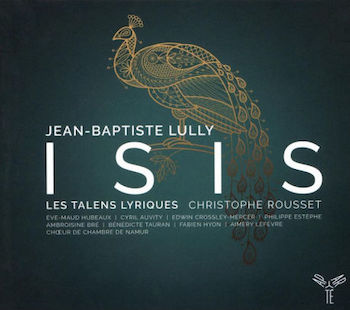

Jean-Baptiste Lully: Isis

Jean-Baptiste Lully: Isis

Eve-Maud Hubeaux, Ambroisine Bré, sopranos; Bénédicte Tauran, mezzo; Cyril Auvity, Fabien Hyon, tenors; Edwin Crossley-Mercer, bass. Les Talens Lyriques, Namur Chamber Chorus, conducted by Christophe Rousset

Aparte 216 [2 CDs] 155 minutes

Click here to buy or to listen to the beginning of each track.

In the past few decades, music lovers have experienced the near-death of studio-recorded opera. Most of the recordings of the standard repertory that reach us today — and many recordings of lesser-known works — were made during a staged performance or else “in concert”: that is, with the orchestra on stage and the singers standing in front but without sets, costumes, or any action beyond, perhaps, entrances, exits, and some bodily gestures. Recordings made before an audience can often feel more alive and dramatic, but there also tend to be downsides: the voices are often balanced louder than the orchestra (to limit distracting coughs and rustling from the hall), or a given singer didn’t “prepare” a certain high note well. Some recordings try to get the best of both worlds by blending a performance (or parts of two performances) with rehearsals or post-performance patch sessions.

In the world of Baroque opera, though, studio recordings continue to be frequent, perhaps because the works involve relatively few performers (especially in the orchestra) and thus do not entail massive labor costs (if we think of musicians as workers, which of course they are).

A sterling example of what can be achieved under modern studio conditions is the new, nearly complete recording of Lully’s Isis by Les Talens Lyriques, the performing organization run and conducted by Christophe Rousset.

For a taste of what I’m about to talk about, click on the link at the top of this review. Or watch this three-minute trailer, which features most of the singers I mention below (and catches some of them having a lot of fun):

Back in the 1960s and ’70s, I didn’t believe what I kept reading about Lully in music-history books. He seemed a duffer to me. Now I know that the problem was the performances available on recordings. (Fans of the Boston Early Music Festival, of course, won’t need to be persuaded by me, since they surely cherish their memories of two Lully productions at BEMF: Thésée in 2001 and Psyché in 2007.)

The new Isis shows how artfully and at times powerfully Lully and his librettist Philippe Quinault could combine the existing elements of Italian opera (namely recitatives, short arias, and extended sung-and-danced divertissements) to tell an intriguing story. Or actually more than one story, because this work (Lully and Quinault’s fifth collaboration) combines two separate tales from Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

Conductor Rousset summarizes the plot well, and sketches the history of the work, in a six-minute interview in French (with English subtitles). Basically, the story the opera tells is of Jupiter’s love affair with the nymph Io. His wife, Juno, is enraged.

(Opera lovers and record collectors may remember Juno from other works about the unfaithful Jupiter, e.g., Cavalli’s La Calisto or Handel’s nearly operatic oratorio Semele. It’s always a great role, giving fine scope to a spitfire singer, usually a mezzo.)

In Isis, Juno entraps Io and has her guarded by Argus — he of the hundred eyes, some of which are always open at any given time. But Mercury, determined to help Io escape, mounts an opera-within-the-opera, in order to lull Argus (all hundred eyes, that is) to sleep. This lovely and powerful divertissement enacts the tale of Pan and Syrinx, and ends with Syrinx escaping Pan’s clutches by jumping into a riverbank and turning into a stand of reeds. Pan instantly feels the nymph’s sorrow, and his own, and plucks some reeds so nearby shepherds can play on them as he and others sing a touching lament. Needless to say, the sexual politics of such a scene of near-rape and the resulting quasi-suicide of a female character could engage us in extended discussion nowadays.

Two other vividly realized scenes (Act 4) involve Io being tortured, at Juno’s command, by being sent to a frigid land (Scythia, which was understood as being located near the Black Sea) and then to a scorchingly hot smelting room where giants (as I assume they are) are hammering molten iron. In the first, the chorus and strings shiver in quick repeated notes; in the latter, the chorus engages in onomatopoeia, tapping the metal to the repeated syllable “tôt, tôt, tôt” (translated in the booklet as “clang, clang, clang”)

The opera ends with Jupiter promising Juno that his affections will no longer wander, and the couple allow Io to ascend to heaven and be worshiped by “the peoples of Egypt” under her new name: Isis. So Io does finally become the title character of the opera.

The work, first performed in 1677, is so blunt in its portrayal of sexual escapades and rivalry among the gods that it reportedly angered the Marquise de Montespan—the primary mistress of Louis XIV—who was envious of the king’s latest amour, Madame de Ludres. As a result, the librettist, Philippe Quinault, was banished from court for two years. Forty years would pass before Isis would return to the court stage (in 1717).

In the header I have listed the six strongest singers. They are an astonishing crew, singing with firm and beautiful tone but also acting and emoting through the voice, with all kinds of subtle technical devices, such as messa di voce (a diminuendo on a single note) and artful applications of portamento. Two other singers are heard a lot (baritones Philippe Estèphe and Aimery Lefèvre) but are woofier.

Many of the singers perform more than one role. There was historical precedent for this: the bass who played Jupiter in the premiere production at court added the role of Hierax as well when the opera was transferred to the Paris Opéra (which performed for the public at the Palais Royal in the center of Paris). The amount of doubling here goes far beyond that: if one counts roles in the prologue and in the opera, one singer takes five, another eight. In the case of Cyril Auvity (who does five), I can hardly complain — he is one of the most beautiful lyric tenors I have heard recently, and also is capable of rising to great passion as needed. Still, this reappearance of a familiar voice in many different roles made it a little harder for me to follow the action without constant reference to the libretto.

A performance of Lully’s Isis featuring Christophe Rousset & Les Talens Lyriques in Beaune, France. Photo: Palazzetto Bru Zane / Amélie Debray.

Christophe Rousset takes plentiful opportunities to enrich the somewhat skeletal score with varied sonorities. The continuo group consists of five musicians (including Rousset at the harpsichord and organ) playing, at various times, eight instruments. The flutists use recorders in Pan’s lament for Syrinx, and Rousset switches from harpischord to organ in order to add the breathy sound of yet more “pipes” to this at once touching and disturbing number. Tempos always feel just right, and Rousset allows the singers the freedom to color their words with slight portamentos, sudden shifts of volume, and so on. I really felt that I was hearing individuals converse. (It helps that most of the cast members are native French-speakers.)

My one slight disappointment was in the “frozen North” scene: the opening chorus has been recorded separately by other groups, who have made it sound more like actual shivering. Here’s William Christie’s distressed-sounding group. Rousset’s choral singers are admirably light and precise, but, at this moment in the work, sound very stylized, as if they were doing the quick repeated notes in a minimalist piece from our own day. (That’s an interesting parallel, of course. Richard Taruskin has pointed out that conceptions of how to play early music often reflect the aesthetic trends of the day. For example, 1950s recordings of Baroque music bear some resemblance to the “objectivity” — e.g., lack of expressive tempo changes from phrase to phase — in mid-century works by Stravinsky and other modernists of a neoclassical bent.)

The sound is superb, reminding us of the marvels that can be achieved by first-rate musicians working under studio conditions for three days. Like the De Sabata Tosca, Rousset’s Isis will be considered a classic for decades to come. Fortunately, it is available on YouTube, Spotify, and other streaming services. But you don’t get to read the booklet, which contains a detailed synopsis, a highly informative essay, and the libretto, all in French and clear English. For that you have to either buy the recording (as CD or digital download) or subscribe to Naxos Music Library.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The review first appeared, in a somewhat shorter version, in American Record Guide and is posted here by kind permission.

Tagged: Aparte, Baroque opera, Christophe Rousset, ISIS, Jean-Baptiste Lully, Les Talens Lyriques