Arts Remembrance: Old-Time Radio Announcer Frank Gallop — A Wonderful Set of Pipes

By Betsy Sherman

Feisty, funny, frightening when necessary, Boston’s Frank Gallop classed-up the airwaves.

Frank Gallop in 1951. Photo: Wiki Common

The 30th of June, 2020, marked the 120th anniversary of the birth of Frank Gallop, a figure who, in the mind’s eye of old-time radio listeners, was the quintessential Bostonian snob.

Never mind that he was not the product of Andover and Harvard, but of the public schools of Dorchester — the successful radio and television announcer lent an elegant presence to an array of programs that encompassed drama, comedy, variety, and public affairs. Though a peripheral figure in American show business, Gallop represents how one can seize on the possibilities of a young medium and, with talent and a wonderful set of pipes, build a varied and prestigious career and amass some quirky credits that made their mark on 20th-century popular culture.

A graduate of the Oliver Wendell Holmes School and Dorchester High, Gallop pursued a career as a stockbroker in Boston’s Financial District. While he was a bond salesman, a client whose company sponsored a radio show asked Gallop if he could do a last-minute fill-in for their show’s announcer. What started as a lark became a passion. Soon Gallop would rush out of the investment firm’s doors at 3 p.m., when the stock exchange closed, to audition at local radio stations for announcing spots. In 1934, he quit the financial field and started working for Boston’s WEEI (originally owned by Edison Electric Illuminating Co.).

It wasn’t long before Gallop and fellow Boston announcer Ed Herlihy made the move to New York (Herlihy would much later appear in Martin Scorsese’s The King of Comedy as announcer of the fictional Jerry Langford Show). Gallop’s low, crisp voice was in demand to narrate radio series such as Gangbusters, Damon Runyon Theater, and a bouquet of soap operas including Stella Dallas, When a Girl Marries and Amanda of Honeymoon Hill. As United Press reporter William Ewald wrote in 1957, in language I wish I could get away with, Gallop was “an announcer whose mellow tones have been caressing the nation’s tympani for more than 20 years.”

It took the great Nat Hiken, creator of tartly funny ’50s and ’60s TV sitcoms The Phil Silvers Show (a.k.a. Sgt. Bilko) and Car 54, Where Are You?, to bring out Gallop’s comic potential. Hiken was head writer on comedian Milton Berle’s Philip Morris–sponsored radio show that ran from 1947 to early 1948. It was a ratings failure, but because of Hiken’s absurdist comic sensibility, it holds up much better today than Berle’s hit TV show, the one that made the comedian a household name.

Announcer Gallop was, in the show’s universe, a Boston Brahmin. He’d start The Milton Berle Show with a pitch for Philip Morris (of “all leading cigarettes,” theirs were “recognized by eminent nose and throat specialists as definitely less irritating”), then make the formal show intro. But instead of a graceful hand-off to the brash New York comic, there’d be a lovely bit of tension, with Gallop serving as a speed bump on the host’s way to the monologue.

None of this announcer deferring to the star; oh no, Berle was made to defer to “Mr. Gallop.” Gallop called him “Berle” or, occasionally, “peasant.” Berle could exact a bit of revenge by taking a jab at the tall, thin Gallop’s physical appearance: the picture painted for the audience was that he was a walking cadaver.

Berle: “Mr. Gallop, you seem so peppy tonight. You must have switched to a different embalming fluid.” Ba-dum-bum.

Each episode had a topic; it could, if listeners were lucky, tease out a portion of the Gallop persona’s backstory. On the show titled Salute to Politics, Berle asked whether Gallop’s family were politically inclined. Gallop allowed that they were rather conservative: “Dad is still chairman of the Beacon Hill Committee to Bring Back George III.”

After the show’s demise, television beckoned to all concerned. While Gallop did some announcing for Berle’s Texaco-sponsored TV show, and for the Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis–hosted Colgate Comedy Hour, the next show that gave him a chance to be in the comic mix was The Perry Como Show, a variety show written by Goodman Ace. Gallop engaged in banter with the singer, but not on screen—he was an unseen “voice from the clouds.” Eventually he’d make select appearances; one time during the early ’60s, he wore a Beatles wig.

The circumstances under which Gallop’s face became known weren’t exactly flattering, but they made for another twist in his career path. Lights Out had been a popular radio show, presenting spooky stories to listen to in the dark. For its transition to live television, its makers hit on a way to establish a macabre mood by making the narrator a startling disembodied head (this being the days of black and white, it was sufficient that the actor wore a black turtleneck and bright light was pointed at his face). Briefly, Jack LaRue played the role, but once Gallop succeeded him in 1949, all that cadaverous promise was fulfilled. Makeup on the show was done by Dick Smith, who went on to fame turning Marlon Brando into Vito Corleone for The Godfather.

Gallop was often back in Boston, appearing on stage as master of ceremonies for concerts and variety shows. According to an item in the April 24, 1955, Boston Globe, Gallop was emcee for General Motors’ Motorama of 1955, an auto extravaganza that included a stage show with singers, dancers, and showgirls, with a finale in which GM “dream cars” rose out of the ballroom floor of Commonwealth Armory on elevating turntables, accompanied by six “girl violinists” garbed in silver.

The ’60s brought another twist to Gallop’s career path when he became part of the stock company of Bob Booker and George Foster, record producers who had written for the massively popular John F. Kennedy–parody album The First Family. Gallop became a mainstay in the comedy record series that started with the 1965 You Don’t Have to Be Jewish (meaning, to enjoy this humor), introducing sketches featuring a cast that included Lou Jacobi, Betty Walker, Phil Leeds, and a pre–Mary Tyler Moore Show Valerie Harper.

For the sequel LP, When You’re in Love, the Whole World Is Jewish (this is the one I grew up listening to), the writers conceived a Yiddishized spoof of a recent hit single by Bonanza star Lorne Greene—the solemnly recited-to-music ballad of a gunslinger, Ringo. To recite The Ballad of Irving, the producers chose, not one of their New York–accented Jewish cast members, but the against-type Gallop. Backed by a lusty male chorus, Gallop intones the mock-tragic tale of “dum-dum Irving … the hundred-and-forty-second fastest gun in the West.” The underachiever rides into town “shlepping a salami and pumpernickel bread,” and keeps kosher (“He always followed his mother’s wishes/Even on the range he used two sets of dishes”).

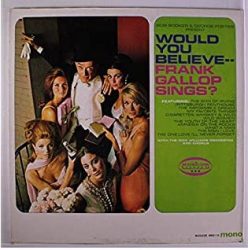

The song spun off the album into a single, and was a novelty hit. But as so often happens, it spawned an inferior, retread sequel—The Son of Irving, whose name is Seymour. Irving’s success prompted Booker & Foster to give Gallop his own LP: the cover of the 1966 Would You Believe – Frank Gallop Sings shows the “walking cadaver” surrounded by beautiful young women. The Ballad of Irving earned Gallop a place on one of Dr. Demento’s anthology albums.

The song spun off the album into a single, and was a novelty hit. But as so often happens, it spawned an inferior, retread sequel—The Son of Irving, whose name is Seymour. Irving’s success prompted Booker & Foster to give Gallop his own LP: the cover of the 1966 Would You Believe – Frank Gallop Sings shows the “walking cadaver” surrounded by beautiful young women. The Ballad of Irving earned Gallop a place on one of Dr. Demento’s anthology albums.

Gallop hung up his microphone and retired to Palm Beach, FL, where he lived until his death in 1988 at age 87. Feisty, funny, frightening when necessary, Mr. Gallop classed-up the airwaves.

Betsy Sherman has written about movies, old and new, for the Boston Globe, Boston Phoenix, and Improper Bostonian, among others. She holds a degree in archives management from Simmons Graduate School of Library and Information Science. When she grows up, she wants to be Barbara Stanwyck.

Betsy,

You’ve left me SO nostalgic for my old radio-tv-loving days! But I never thought that you went back THAT far. On to Westbrook Van Vorhis!

Good commentary!

Nat

I want to cry.

Watching “Lights Out” this evening on YouTube. I came across your story and found it very interesting. Sort of strange to find it on the anniversary of his birth. Thank you for a well written article.