Book Review: “The Fallen” — Probing Cuban Paralysis

By Lucas Spiro

The Fallen artfully diagnoses the spiritual and material maladies of contemporary Cuban life through the lens of a single family, a household threatened by decay, exterior and interior.

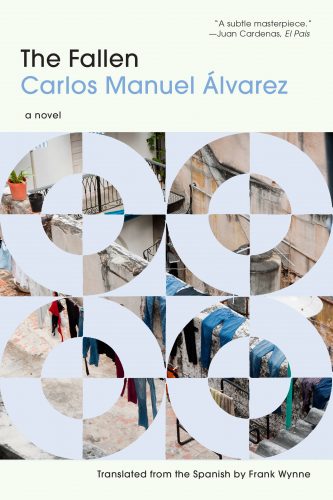

The Fallen by Carlos Manuel Álvarez. Translated from the Spanish by Frank Wynne. Graywolf Press, 160 pages, $16.

Cuba has long been thought of as a nation frozen in time. Tourists visit to see cars from the ’50s on the cobbled streets of La Habana Vieja, which are densely lined with Havana’s iconic colonial architecture. Maybe they even convince themselves they can hear the last clink of a gambler’s mojito glass echoing in eternity — before Fidel and Co. snuffed out the good times on Pleasure Island. Of course, this is a naïve misunderstanding. Many writers have attempted to demolish the stereotype of “time-capsule” Cuba. The truth is that, since the Revolution, Cuba has undergone vigorous periods of cultural, artistic, social, political, and economic transformation. Granted, the country’s history and its fraught relationship to the rest of the world (not least of all the United States and the former Soviet Union) has inevitably meant that historical oddities exist alongside new growth. The country’s past is densely layered: in Old Havana, for instance, there are centuries of architectural styles worthy of preservation.

Cuba has long been thought of as a nation frozen in time. Tourists visit to see cars from the ’50s on the cobbled streets of La Habana Vieja, which are densely lined with Havana’s iconic colonial architecture. Maybe they even convince themselves they can hear the last clink of a gambler’s mojito glass echoing in eternity — before Fidel and Co. snuffed out the good times on Pleasure Island. Of course, this is a naïve misunderstanding. Many writers have attempted to demolish the stereotype of “time-capsule” Cuba. The truth is that, since the Revolution, Cuba has undergone vigorous periods of cultural, artistic, social, political, and economic transformation. Granted, the country’s history and its fraught relationship to the rest of the world (not least of all the United States and the former Soviet Union) has inevitably meant that historical oddities exist alongside new growth. The country’s past is densely layered: in Old Havana, for instance, there are centuries of architectural styles worthy of preservation.

On any given day, one of these old buildings is liable to collapse, and these disintegrations suggest that something is desperately wrong. Vulnerable Cubans live within the decaying structures of a distressed economy and a restrictive political system. These aged buildings — beset with rot on the outside and the inside — are symptomatic of a troubled history and a precarious present. And these fragile edifices are symptomatic of the Cuba Carlos Manuel Álvarez limns in his debut novel The Fallen, translated from the Spanish by Frank Wynne. The volume artfully diagnoses the spiritual and material maladies of contemporary Cuban life through the lens of a single family, a household threatened by decay, exterior and interior.

Contrary to those writers fighting against the notion that Cuba is frozen-in-time, Álvarez envisions the country as an island in the grip of stasis. He does not think that dynamic or vital energies drive the glaring contradictions in Cuban society. He approaches what he sees as a cultural sickness as if he were a doctor, though he makes use of metaphors instead of a stethoscope or scalpel. Perhaps a coroner might be a better description; his Cuba seems to be in a terminal condition, beyond doctoring.

The story is crafted in five short chapters comprising four sections each. Each section is told from the perspective of a different family member: the father, son, mother, and daughter. The son, Diego, is 19 years old and begrudgingly fulfilling his compulsory military service. He resents his restrictive society; he wants to finish his service as quickly as possible and then attend university. (He may be closest to Álvarez in outlook and conscience.) He fluctuates between philosophical observations about objects and his family and fighting the boredom and uselessness of his military duty. He is preparing for what he calls the war that never comes. Diego meditates on his home and the “old wooden window frames in the bedroom” that “will carry on rotting for all eternity.” In his barracks, he muses about how “anything that breaks the silence clearly benefits the soldier and his mental health. You walk along the hall, your gaze sliding off things, seeing nothing in particular, as though the objects, forms, and concepts that make up the world refuse to be observed.”

The father, Armando, is a true fidelista, a believer in the Revolution. He is the director of a hotel in the city where the family lives. Here the local economy is sustained by tourism. He thinks of himself as “an honest man,” someone who can “endure, a man who knows that the heroes of our country endured much worse, a man who knows that real men hold their pain inside.” Armando’s life is beset by many minor inconveniences. The ’95 Nissan he drives, “quite new,” continually breaks down or runs out of gas, even though he puts his full gasoline ration in the tank. No more, no less. His steadfast belief in the State and its simple proverbs makes him look like a fool. His son and daughter reject his kind of devoted servitude to the past. Armando’s ideology boils down to a single anecdote he tells about Che Guevara. One day, when Che was touring a bicycle factory, the manager tried to give him a bike for his daughter. Che refuses the gift because “they belonged to the State and he had no right to give them away.” Still, even Armando can’t remain puritanical all the time; he habitually drinks a little too much in the evenings. He also has his own rebellious ideas about the nature of Cuba’s illness, which are also related to stasis. “These days,” he says, “people take what they are given, and sometimes what they’re not given too. Sometimes I cannot help but think – not that I would say it, obviously – that the heroes of the Revolution had it easier than I do. People say times were hard back then, but the hardest times are those when no one wants to do anything, times marked by a crisis of values, a spiritual simple-mindedness, too little determination.”

Mariana, the mother, is a former teacher. She retired after a bout with cancer and now suffers from a debilitating form of epilepsy: she constantly collapses. Like the country’s falling buildings, she is a structure in decay. The doctors say her seizures are a reaction to the chemotherapy used to kill the cancer; the cure is a poison. Her mental faculties, too, are beginning to erode. Family members are on edge about Mariana’s condition, but their empathy is weakening as she falls further and further into disrepair.

According to her father, Maria is someone who never beats around the bush, who at a young age began “learning to master the art of scarcity.” Yes, she practices a brutal pragmatism, but it is the result of a different lesson than her father thinks. Maria is one of the people who takes more than is given to them — she is stealing from the hotel. She has learned to survive, but by engaging in the everyday corruption that thrives in authoritarian political systems and which, to a degree, sustains them. Maria’s emotionally and physically starved childhood has led her believe that “there’s no such thing as a best friend, no one is anyone’s friend, everyone is alone.” If her father weren’t so ideologically blind he might see that his daughter is far less innocent than he wants to believe.

The Fallen is about a Cuba deeply affected by the tumult of the preceding era, the end of the Soviet Union. People forget that the liberalization of Russia’s economy in the ’90s was one of the worst humanitarian disasters in history, with lasting consequences for its allies. After the dissolution of the USSR, Cuba’s economy went into free fall. This time in Cuba’s history is euphemistically referred to as “the Special Period.” Privation and economic hardship fuel Diego and Maria’s resentment toward the older, more restrictive generation. For Álvarez, “the Special Period” signaled the end of the Revolution. There is no medicine or operation that will ameliorate the lingering sickness of what’s left of Castro and his ideology in Cuba.

Álvarez is also a journalist, a co-founder of the news website El Estornudo, or “the sneeze.” The site is often critical of the Cuban government; it is regularly harassed by the police because of its editorial perspective. Álvarez was recently detained and questioned by the authorities while traveling to Mexico City, where he spends half his time.

That said, Álvarez’s prose in The Fallen is far from journalistic. His book is stuffed with striking metaphors. Some are quite evocative, if enigmatic. The father begins his opening monologue with the phrase “Days like rabid dogs.” What does this mean? It might be a Cuban saying that doesn’t translate well into English — regardless, it evokes plenty. Sickness, monotony, and danger. Conventional wisdom suggests there’s only one way to deal with a rabid dog. A dissipating friendship is “like a car that continues to coast for a few meters after the engine is turned off.” The image resonates with Armando’s auto, which is taking its slow run toward breakdown.

Author Carlos Manuel Álvarez — he embraces a Joycean aesthetic as a means to diagnose postcolonial paralysis.

Sometimes the language is affected in a way that suggests a young writer showing off for their MFA professor. The novel contains some “MFA-ification,” which relies heavily on modernism’s predominance in how writing is “taught.” Sometimes the book’s prose is glaringly signposted, a highlighting of symbols that reflects Álvarez’s self-conscious resonances with James Joyce and Dubliners. Of course, there are strong parallels: both books are studies of interiority in a postage-stamp-sized, troubled island that’s suffering from a kind of paralysis. The Fallen departs from realism, though, inheriting elements of Cuban magic realism from the likes of Alejo Carpentier. The Fallen is billed as a novel, but it is essentially a collection of impressionistic sketches, teasing out phenomenological observations of perception, memory, and truth. In fact, Álvarez’s strength as a writer lies in the short story, especially in his use of compression via metaphor. In one scene, the mother describes her husband’s movements as “so slow that his every action already contains within it its own repetition.” Motion and stasis — interwoven.

But Álvarez’s dependence on metaphor gets him into trouble. A stultifying pessimism runs throughout The Fallen, the result of the author’s dependence on an overwrought picture of decadence that pulls everything in the narrative in one direction. Despite the story’s use of multiple perspectives, The Fallen comes off as monologic. Cuba’s closed-off environment is heavily underlined — with charcoal. The overarching metaphor of dissipation makes a spectacular appearance in this look at the behavior of caged chickens:

There are various causes that can trigger cannibalism in poultry. Excessive heat, overcrowding in the hatchery, especially around the feeders and the drinking troughs, poor diet, and a lack of protein. Weak or crippled chicks suffer a lot. In better cages, boredom is an inherited vice. And it is this boredom that is the main reason why innocuous chickens, terribly innocuous chickens, lethally innocuous chickens, end up pecking at each other, eating each other’s entrails.

Armando and Mariana, their daughter notes, have a thing about chickens which goes back to a particular dinner they had during “the Special Period.” They had the rare opportunity to eat a freshly butchered bird. The children, unused to meat, opt for something simpler, not recognizing the emotional importance of their parent’s offering. The children don’t remember this dinner; the parents have internalized their disappointment. This tender, bittersweet misunderstanding resonates powerfully among the book’s characters. But Álvarez squanders its significance by working too hard to make the event summarize Cuba.

I understand Álvarez has an axe to grind. I admire his attempt to embrace a Joycean aesthetic as a means to diagnose postcolonial paralysis. And the approach can be quite effective at times. But Álvarez, even if his analysis is correct, is not immune from the disease he studies. His ability to freely travel back and forth between Mexico and Cuba signifies that he is a special brand of Cuban. The word they use in the country for the Cuban diaspora (as well as for those like Álvarez who also live abroad) is the “exterior,” as opposed to Cubans who reside in Cuba, or the “interior.” Álvarez is both “exterior” and “interior,” a hybrid exile. I respect the writer’s keen perspective, but The Fallen breaks down under its attempt to draw on this duality to make a portentous “total” statement, propelled by Álvarez’s cynical acceptance that Cuba is completely paralyzed.

Álvarez overstates the degree to which Cuba is the island of cannibalistic chickens, or even the sow that eats its farrow. And the independence of his judgment on this issue can be questioned. He may (rightfully) resent the Cuban police pressure he receives as a journalist, but his publication claimed in an article it had a right to receive — without admitting to having accepted — assistance from the National Endowment for Democracy, a US State Department and CIA adjacent regime-change think tank. Even if the site did accept the support, the editorial suggests, it wouldn’t mean El Estornudo was acting on behalf of a foreign power. Still, this possibility of US influence raises uncertainty when reading The Fallen. For example, Diego is deeply skeptical of the government’s paranoia, which is behind his compulsory military service. But aren’t Cuba’s fears justified? There have been countless attempts by the US government to overthrow the Cuban government, assassinate its leaders, starve its economy via embargo, and otherwise sow discord. Álvarez wants it both ways.

The Fallen’s determination to stand outside of politics in order to make a fundamental statement about Cuban society ends up overwhelming the narrative. And that is a shame, because Álvarez is obviously a talented writer, if at times a little too polished, academic, and self-conscious for his own good. It will be interesting to see if he will be able to break out of the conflict posted by his being “exterior” and “interior.” Ironically, the State-led restoration of Old Havana’s architecture has been funded, in large part, by Cuba’s enthusiastically opening up its tourism business, which brings in much-needed dollars from the outside. The very industry in which The Fallen‘s father works is one of the most dynamic parts of the economy. Álvarez chooses to ignore this fact, which triggers some skepticism — or it could be the point. Maybe, for him, tourism does not represent a clean enough break from history, a history that has not yet absolved Castro or his legacy. Sometimes the only way forward is to demolish and start over. As Diego considers how his mother is no longer herself, he might be speaking for Álvarez and his feelings about his homeland:

You tell yourself it’s the disease, but what does that mean? You tolerate this woman who sometimes takes over the body of the mother you know and who you go on calling mother even when there is nothing left of her that bears the slightest resemblance to the mother you knew, except, maybe, certain physical traits, and not even that, because from what they say, in the ugliness that follows the falls, your mother’s lucid gaze is replaced by a vague, trancelike stare; her mouth, usually filled with comments and remarks, becomes dry and twisted, the lips curl into a strange rictus; her skin, warm and pulsating like the skin of all mothers, becomes a pale, withered hide; and her lithe, hyperkinetic body becomes a slow, misshapen mass, flat, motionless, affording no shelter.

Give me shelter, Álvarez seems to implore, give me something vital. I hope he finds it.

Lucas Spiro is a writer living in Dublin.

The NED connection is a big clue that this author is CIA influenced. Maybe readers should take a look at the Grayzone article by Max Blumenthal on this very subject. I think at this point history has absolved the Castro movement for its ending the Batista/Mafia cabal and for its many reforms in medicine, literacy, higher education, mental health programs, international humanitarian projects, revolutionary internationalism against apartheid, mass culture and sport programs, etc. But I guess the proverbial historical judge is waiting for the Cuban revolution to commit suicide before it grants a full absolution. Really well done review.