Book Review: “Here We Are” — Philip Roth’s Boswell

By Helen Epstein

This glimpse into the relationship of two American Jewish writers makes for good reading during the pandemic: an intelligent, gracefully written memoir of friendship.

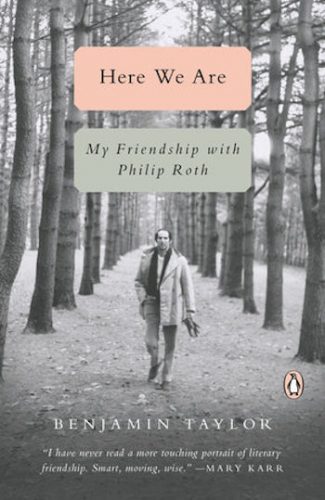

Here We Are: My Friendship with Philip Roth by Benjamin Taylor, Penguin, 192 pp, $26.

“Memory is where the living may rejoin the dead,” writes Benjamin Taylor toward the end of his slim, decorous memoir about his friendship with the late author Philip Roth. “There they anoint us. Through memory we obtain the blessing. Through memory we remain filial. Memory makes us Jacob, not Esau.”

“Memory is where the living may rejoin the dead,” writes Benjamin Taylor toward the end of his slim, decorous memoir about his friendship with the late author Philip Roth. “There they anoint us. Through memory we obtain the blessing. Through memory we remain filial. Memory makes us Jacob, not Esau.”

Here We Are, a glimpse into the relationship of two American Jewish writers, makes for good reading during the pandemic: an intelligent, gracefully written memoir of friendship. Short enough for our wavering pandemic-stressed attention spans, it’s a book sprinkled with bits of literary gossip and literary criticism, if not many surprises. Like several recent memoirs, it mostly skates on the surface of the events and relationships it describes and does not tax the brain, coming off more like a magazine profile than a book.

Roth (1933-2018) was one of the most successful American authors of his generation. Starting with his book of short stories Goodbye, Columbus, which won the National Book Award in 1960, he wrote 31 largely autobiographical books fueled by a childhood in Newark, NJ, as Taylor writes, “as endlessly rediscovered through alchemical imagination, that flame turned up under experience for the smelting of novels.” Roth garnered millions of devoted readers across the world and antagonized millions of others. These included women and other Jews, who found his work predictable, anti-Semitic, self-referential, and misogynistic. Roth won many coveted literary prizes although — much to his chagrin — not the Nobel, which Taylor reports he called the “Anybody-but-Roth-Prize.” I myself admire Roth’s sharp eye, humor, and narrative skill but find his protagonists too close to age-old and still current stereotypes of Jewish males (the witty neurotic; the sex-obsessed despoiler of gentile women). His sensibility is too parochial for my taste.

Author Benjamin Taylor is a very different kind of writer and a different kind of American Jew. Born in Forth Worth, TX, in 1952, well after the second world war that so marked Roth’s boyhood, Taylor is understated where Roth is brash, refined where Roth is crude. Taylor quotes Montaigne’s classic aphorism “Parce que c’etait lui; parce que c’etait moi” to explain their friendship, and doesn’t give the reader much information about their respective lives, their other friends, their other activities, or the dynamics between them. He shows the two men appreciating Roth’s jokes and ideas about what’s funny. Taylor describes Roth as his chosen parent of middle age and as his best friend.

“I can’t be the first gay man to have been an older straight man’s mainstay,” Taylor writes in one of his infrequent characterizations of the nature of their relationship. “Philip had searched diligently for a beautiful young woman to see to him as Jane Eyre looked after old Mr. Rochester. What he got instead was me. The degree of attachment surprised us both. Were we lovers? Obviously not. Were we in love? Not exactly. Sufficient to say that ours was a conversation neither could have done without.”

Taylor provides little social context for either of them and does not fully explain the evolution of their friendship. They first met at a party in 1995, when Roth was past 60 and Taylor past 40 and did not make further contact until three years later when, after reading Roth’s I Married a Communist, Taylor wrote to him about a passage in the book. A few days later, Roth phoned him. “I felt at once that I was laughing with someone I knew well. Acrobatically unpredictable though the conversation was, I could follow his moves. Someone had to lead. Then he hung up without notice and I felt I’d been danced off the edge of the world.”

Sounds like infatuation, with echoes of Leonard Cohen, no? In 2001, the two men – Roth now close to 70, Taylor to 50 — finally had a meal together on the Upper West Side of Manhattan where Roth lived on 79th Street –- sharing the first of what Taylor writes would become “hundreds of meals.” Roth had sent Taylor his latest novel The Dying Animal and wanted to discuss it. “Determined not to gush,” Taylor recalls, “I said that the scene where Consuela Castillo shows David Kepesh her doomed cancerous breasts reminded me of a similar scene in Solzhenitsyn’s Cancer Ward in which a girl, on the night before her mastectomy, goes to the room of a boy sick with a cancer of his own and chastely asks him to worship her doomed right breast. ‘Today it was a marvel. Tomorrow it would be in the trash bin,’ I said, quoting Solzhenitsyn. In the silence that followed, I felt our friendship begin.”

As a student of memoir, I’ve learned that a memoirist is not always fully aware of the implications of what he or she has written. In this passage as in many others, I also recalled lopsided relationships I’ve had with older people (including gifted men such as Meyer Schapiro and Joseph Papp – both revered mentors to gay and straight men). In my reading, Roth seems to have regarded Taylor not only as a friend and companion of his old age but as his nurse, scribe, archivist, and possible biographer, although he had chosen an official biographer – Blake Bailey – in 2012. Taylor performs some of these functions in Here We Are, reproducing jokes, bon mots, and one-liners that he has jotted down verbatim; quoting from Roth’s work to illustrate his evolution as a writer:

Early on he told me this: “What I care about is individuals enmeshed in some nexus of particulars. Philosophical generalization is completely alien to me…” I mentioned a few characters of his whose intense particularity touches the universal: Mickey Sabbath, Swede Levov, Coleman Silk.

“Glad for the vote of confidence but I aim only at specifics. Entirely for others to say whether some universal has been hit. I have for instance never—I repeat, never—written a word about women in general. This will come as news to my harshest critics but it’s true. Women, each one particular, appear in my books. But womankind is nowhere to be found.”

Roth, unsurprisingly, is never described as asking Taylor any questions about himself. In one of the all too few telling scenes of the memoir, Taylor, who loves planetariums, has dinner with Roth after seeing the show at the Hayden Planetarium. Excitedly, he informs Roth “that the mass-energy of the universe is made up of 5 percent ordinary matter and energy, 27 percent dark matter, and 68 percent dark energy. So dark matter makes up 85 percent of the total mass of the universe” and reminds Roth of a sentence from The Human Stain: “There really is no bottom to what is not known.”

“‘You’re talking a lot tonight,” Taylor reports Roth responding, “’Eat your supper.’ What he was not interested in he was not interested in.”

My irritation with Roth was balanced by my sympathy for Taylor, whose patient attentiveness shows how deeply he loves the older man. Taylor plays Boswell as best he can and reports some (for me) new information about Roth’s life.

The hyper-prolific novelist wrote even more than we thought, including some 1,000 pages of unpublished manuscripts: “Notes for My Biographer,” a book-length refutation of Claire Bloom’s memoir Leaving a Doll’s House (“whose publication Philip counted among the worst catastrophes of his life and credited with his failure to win the Nobel.”) and a full-scale book called “Notes on a Scandal Monger,” that “sought to even the score with his earliest anointed biographer and afterward ex-friend, Ross Miller, dedicatee of The Human Stain, who he felt had betrayed him by failing to work effectively and in a timely way on the project…. The appetite for vengeance was insatiable. Philip could not get enough of getting even.”

Apparently, Roth liked the idea if not the actual process of getting married. “Philip was a great proposer of marriage… He would propose in jest. He would propose in earnest. He would propose in town and in the country. He would propose on brief acquaintance. He would propose on condition that there be no patter of little feet. In his seventies he would consult with doctors on the odds of fathering a defective child, and then propose. Best was when he proposed to Věra Saudková, Kafka’s niece. She’d lost her position in a Prague publishing firm in 1968 after the Russians rolled in. When he called on her, she let him sit at Kafka’s desk and browse the family albums. ‘I know a way to get you out of Czechoslovakia,’ he told her. ‘Will you marry me?’ She graciously declined.”

More interesting to me was Roth’s difficult medical history. As a young man, he sustained a serious back injury while in basic training that led to several surgeries, including three spinal fusions. At 50, he was diagnosed with heart disease and, at 56, underwent a quintuple bypass. At 70, “a defibrillator was installed” that required repeated adjustments. Two years before he died, his aortic valve was replaced.

Those hard and specific details emerge only in the last chapter of Taylor’s memoir. There Roth has reached the age of 85 and lies dying in a New York City hospital, surrounded by a cluster of other (unnamed) friends and former lovers. Taylor tells us that Roth has prepared for suicide if need be: “He kept in his safe … pills, a plastic bag and band with which to affix it to the neck. Also a box of Triscuits. He’d been told of people throwing up after taking the barbiturates on an empty stomach. ‘I want you to know that a day may come when I’ll need your assistance, if only to hand me those things from the safe. You’ll be in no legal jeopardy. I’ve checked on that.’”

Taylor is reticent in his account of his friendship with Roth in Here We Are. He’s a mordant writer when he wants to be but seems to back off from delving into any depths in this book. Taylor focuses his attention almost solely on the great older man he reveres. I wanted to read more about Taylor and what he brought to the relationship. He’s almost the polar opposite of Roth, discreet, careful, protecting both himself and his mentor. If you are a Roth fan, you will eat up this book and love the details he provides, such as “At our leave-taking, I said, ‘You have been the joy of my life.’ “And you of mine,” he replied.’”

Helen Epstein (www.helenepstein.com) has published 10 books of non-fiction and has been reviewing for The Arts Fuse for 10 years.