Visual Arts Feature: Memories of a Veteran Boston Gallerist — Mario Diacono

By Charles Giuliano

Mario Diacono’s Boston shows were legendary.

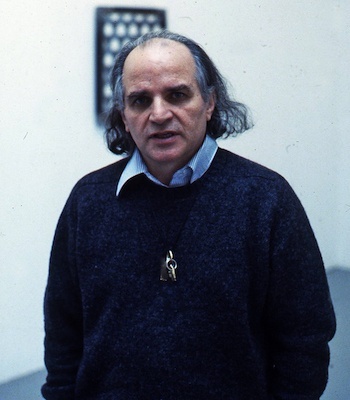

Italian born gallerist Mario Diacono moved to Boston in 1985. Photo: Charles Giuliano.

Now 90, the Italian-born gallerist Mario Diacono lives with his wife Claudette in Brookline, MA. He moved from Rome to Boston to be with her in 1985. Several months later he established a singular avant-garde gallery in the city.

First in Bologna, Rome, then in Boston, Diacono exhibited one or two works for which he wrote essays that were published as gallery handouts. In Boston he wrote them in Italian; they were translated into English by Marguerite Shore.

“In 1984 I published all of the essays I had written for the galleries in Bologna and Rome,” he told me recently. “In 2010 and 2012 all of the pieces I had written for the galleries in Boston and New York (with Perry Rubenstein). I didn’t count them, but between the three volumes [there are] well over 120 essays.”

Diacono’s primary interests were Neo-expressionism and Neo-Geo, and this coupling of creator and writer led to his collaborating with many of the leading artists of our time, including Jean Michel Basquiat, David Salle, Francesco Clemente, Sandro Chia, Vito Acconci, Eric Fischl, Peter Halley, Ross Bleckner, Rosemarie Trockel, Roni Horn, Joseph Kosuth, Alex Katz, Julian Schnabel, Annette Lemieux, and Damien Loeb.

The first of Diacono’s several Boston spaces was located on Peterborough Street, in the Fenway. It had been the studio of then emerging artists Doug and Mike Starn.

A concrete and visual poet, Diacono first came to the US to teach at University of California, Berkeley. “That lasted until the summer of 1970. My Fulbright grant was expired so I returned to Rome,” he explains. Later, teaching at Sarah Lawrence College provided proximity to New York studios and galleries. Diacono’s first gallery was in Bologna, 1978-1979, followed by a gallery in Rome from 1980 to 1984. He introduced American artists to Europe, including Acconci, Schnabel, and Basquiat.

Regarding Basquiat, “I bought the work in 1982 directly from Annina Nosei…. In 1984, when I was in NY, I met him a few times. We met in the street. I was with Nosei, and he didn’t want to talk too long with me because he didn’t want to talk to Nosei. The next time was in Mary Boone’s gallery…. He was very polite but we didn’t exchange many words, didn’t have much of a conversation. He was completely involved with himself.”

Basquiat’s painting Il campo vicino l’altra strada (“The Field Next to the Other Road”) failed to sell during its first exhibition in Rome. Two years ago, the painting sold for $35 million.

Julian Schnabel during his ’80s exhibition in Boston. Photo: courtesy of Charles Giuliano.

Major Boston collectors like Graham Gund visited Diacono’s gallery but didn’t buy. Curator Ted Stebbins purchased a couple of works for Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts. “He bought for the museum a big Ross Bleckner painting in 1986. The museum also bought a work by Sherrie Levine, in, I believe, 1988,” Diacono recalls.

“My first Boston show was a huge painting by Alex Katz. After him I showed Eric Fischl and Ross Bleckner. I showed later, twice David Salle, and once each time for Julian Schnabel, Francesco Clemente, Sandro Chia, etc. I never sold any of those works in Boston.”

Another possible MFA sale fell through. “At the opening of the Philip Taaffe show, Alan Shestack (then the MFA director), stayed for an hour. He told me ‘I am waiting for Trevor Fairbrother (MFA curator) who is coming to decide if we want to buy a painting from you.’ Fairbrother didn’t show up. Shestack went away and never came back.”

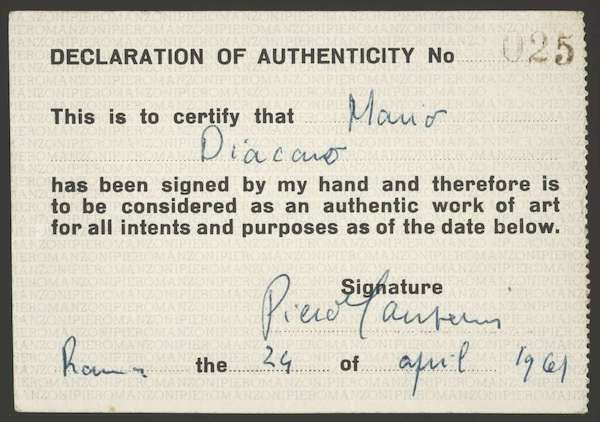

Ironically, Fairbrother later asked Diacono for a favor. “I would like you to make a donation of a work in my name to the MFA,” remembers Diacono. “I gave to the museum my certificate of being a living art work by Piero Manzoni. Today it could be worth $100,000. I donated it, and didn’t even ask for a tax break.”

Survival in Boston was challenging. “I sold two works to the MFA. There was also a collector, Dr. Bernardo Nadal-Ginard, who bought an Enzo Cucchi and a Ross Bleckner. Later, it was said that Nadal-Ginard had cashed in advance his own pension (for which he was convicted and served a one-year sentence). He put together an important collection which was later taken over by Harvard University and auctioned, making a very large amount of money. He is still a major collector.”

There were few sales in Boston but Diacono says, “I also sold at least a couple of works each to Marjory Jacobson, Dorothy Lavine, Karen Meyeroff Sweet, and Ken Freed. They were important supporters of the gallery, especially in the years 1985-1990.”

Manzoni certificate that Mario Diacono donated to the MFA. Photo: Charles Giuliano.

Diacono formed a relationship with Achille Maramotti, the founder of the Italian fashion house Max Mara. “I sold works from all my shows to him and they are now on view in Reggio Emilia,” he says. “The collector, who was also a close friend, died in 2005 at 78. In 1976, he came to New York for business and we got together every day. He was mostly collecting from the Scuola Metafisica (metaphysical art) period: Giorgio Di Chirico, Carla Carrà, Giorgio Morandi, those artists. We decided together that he would focus on collecting the artists of his own time.”

Why not live in Italy? “I hate Italy” is Diacono’s emphatic answer. “Because of what Italy is. It’s a corrupt and backward country. Not because of the people, but because of the ruling political class. I have despised the major political parties and the government all of my life.” In 1956 he was a member of the Communist Party — until Russian tanks invaded Hungary. “I gave up my Communist Party membership card. From then on, I have been a leftist without a party.”

During the pandemic he is staying put: “Primarily I am active as an unofficial curator of the Maramotti Collection. It involved a lot of traveling until 2015, when I had a hip replacement surgery. Then in 2016 I had knee replacement, and later surgery on my spine.”

Diacono’s Boston shows were legendary. His poetic, theoretical essays, however, were difficult, to the point of being off-putting. With a note of whimsy, he explains that “they were challenging for me too, to write.”

Charles Giuliano has published six books and is researching an oral history of contemporary fine arts in Boston.

Excellent summary of Diacono’s importance as a pioneering Avanti-garde gallery in Boston.. Very helpful for my research. Many thanks.

A few minor details are wrong here. In short, I was crazy about that big Phillip Taaffe painting (inspired by a cast iron railing in a NJ train station, I believe). I don’t remember being a no-show at the opening. Alan Shestack definitely knew how much I wanted to acquire it, and it just didn’t happen. It was his decision. It wasn’t the only time he said no to acquisitions I proposed. That’s life in the museum biz.

For the record, I was a cheerleader for the Bleckner acquisition that happened when Ted Stebbins was acting curator of contemporary art. I was working for Kathy Halbreich when the contemporary department purchased the two Sherrie Levine paintings from Mario. When I was curator I purchased works by Ellen Gallagher and Rosemarie Trockel from Mario.

It was great that Mario donated the Piero Manzoni. I think he was happy to do that and I think he knew that I was doing my job. The main point of the article is spot on … Mario’s Boston shows were very special and inspiring.

Response from Mario Diacono (via Charles Giuliano):

Trevor is correct in most of his notes about our interview, except for his no-show at the Taaffe opening.

I have told this story to friends enough times in the last 30 years that it’s impossible that my memory about that day was failing.

I love Trevor anyway, I gave my Manzoni certificate to the MFA in his honor because he was doing an excellent job, and I don’t regret it.

Molto interessante! Andrea Ugolini