Book Commentary: “Pale Horse, Pale Rider” and the Literature of COVID-19

By Bill Marx

“The body is a curious monster, no place to live in, how could anyone feel at home there? Is it possible I can ever accustom myself to this place?”

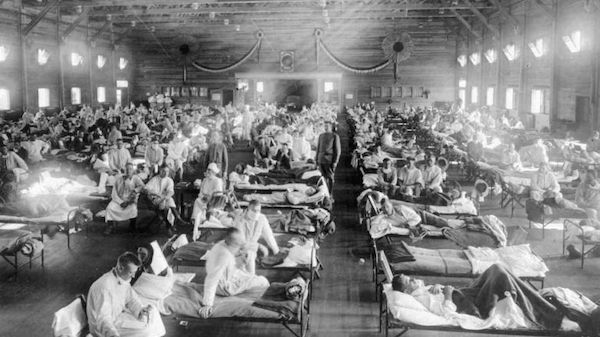

Patients in an emergency hospital in Camp Funston, Kansas, during the 1918 flu outbreak. Photo: AP / National Museum of Health.

Will there be novels and short stories about COVID-19 and how it may be changing us? Judging by how little literary attention the 1918 influenza pandemic received, my guess is that there might not be. It is intriguing to wonder why there was so little interest a hundred years ago. At the very least, speculation might stimulate some of today’s writers to take the risk. But first they will have to grapple with why they might feel paralyzed. And I think some of those reasons resonate with problematic attempts to write imaginatively about the current Climate Crisis.

F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, John Dos Passos, Sinclair Lewis, and Sherwood Anderson never dealt with pandemic in their work. Among those who did were Thomas Wolfe (a chapter in 1929’s Look Homeward, Angel);William Maxwell in his 1939 novel They Came Like Swallows, which is about a Midwestern family that falls ill when the flu reaches their town; and John O’Hara in his 1935 short story “The Doctor’s Son.” The latter contains a whiff of class conflict via its adolescent narrator. (O’Hara was 13 in 1918.)

The mines closed down almost with the first whiff of influenza. Men who for years had been drilling rock and had chronic miner’s asthma never had a chance against the mysterious new disease; and even young men were keeling over, so the coal companies had to shut down the mines, leaving only maintenance men, such as pump men, in charge. Then the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania closed down the schools and churches, and forbade all congregating. If you wanted an ice cream soda you had to have it put in a cardboard container; you couldn’t have it at the fountain in a glass.We were glad when school closed, because it meant a holiday, and epidemic had touched very few of us. We lived in Gibbsville; it was in the tiny mining villages — “patches” — that the epidemic was felt immediately.

The most powerful of all, because it centers on the flu, is Katherine Ann Porter’s longish story “Pale Horse, Pale Rider,” which was based on the writer’s struggle with the disease when she was working (as a theater critic!) for the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Porter’s “landlady, fearing infection, threatened to have her evicted from her rooming house, so the newspaper’s city editor finagled her admission to an overcrowded hospital. She ran a 105° fever while lying on a gurney in a hallway for nine days. Her doctors expected her to die, the newspaper drafted her obituary, and her family made arrangements for the burial, but an experimental injection of strychnine helped her to recover from the virus.” She was a survivor and the hellish experience, as she recounted it in a 1963 interview, was seminal: “It simply divided my life, cut across it like that. So that everything before that was just getting ready, and after that I was in some strange way altered.”

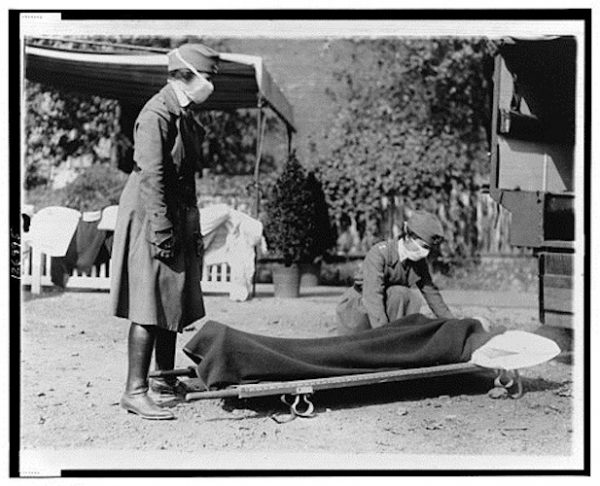

A scene from the 1918 flu outbreak. Photo: AP / National Museum of Health.

The catastrophe didn’t draw a traumatic dividing line for other writers, or create a before and a radically different after. One argument for this response is that Fitzgerald and the others of his “lost” generation were too close to the chaos. It took time to deal psychologically with the horror: 500 million people, about a quarter of the world’s population, perished; 675,000 Americans died, more than were killed in all the wars of the 20th century combined. It took a decade for Wolfe to tackle it — the others never did. Another line of reasoning has it that the mass death in the homeland was subsumed (sublimated?) into the hellishness of World War I. The senselessness of the flu was intimated through the insanity of the war, which also gave writers an opportunity to lash out at those they felt were responsible for instigating the mindless destruction.

There is another possibility. In his essay The Forgotten Apocalypse, David A. Davis speculates on the lack of literary attention the momentous outbreak of influenza received.

But why are there not numerous other literary texts about the pandemic? One might expect that the convergence of a war and a pandemic would lend itself toward literary representation, but this, curiously, has not been the case, which complicates the idea of cultural trauma as an experience that marks a group consciousness. In The Great Influenza, John Barry, discussing the scarcity of literary depictions of the pandemic, comments, “People write about war. They write about the Holocaust. They write about horrors that people inflict on people. Apparently they forget the horrors that nature inflicts on people, the horrors that make humans least significant.” The answer to the persistent question of absence may be that the virus was both amazingly horrendous and completely ordinary. It was an enormous collection of personal tragedies that collectively amounted to a global calamity.

Perhaps the answer may be the kind of cultural trauma that is being considered — the depiction of the “horrors that nature inflicts on people.” On one level, Porter’s story attacks the “patriotic” vision of WWI, dramatized through the doomed romance between infected Miranda and her lover, Adam, a doughboy who is about to be sent overseas. He is determined to go to battle, despite Miranda’s fears that his innocence is what the absurdity of war feeds on: “Pure, she thought, all the way through, flawless, complete, as the sacrificial lamb must be.” Adam’s manipulation is juxtaposed with the pressure exerted by official groups throughout the story to have the impecunious Miranda do her duty, as so many others have, and buy Liberty Bonds.

But Miranda’s vivid struggles with the flu go beyond the tragedy of the war, moving into a deeper, subconscious battle with the power of the disease, her delirium generating hallucinations and visions (“… she sank easily through deeps under deeps of darkness until she lay like a stone, at the farthest bottom of life, knowing herself to be blind, deaf, speechless, no longer aware of the members of her own body”). Critic Elizabeth Hardwick noted that Porter’s best stories explore “the unexpected felicities of ‘homelessness.'” The price for Miranda’s survival amounts to a kind of biological alienation, a visceral disconnection that doesn’t come off as felicitous: “The body is a curious monster, no place to live in, how could anyone feel at home there? Is it possible I can ever accustom myself to this place? she asked herself.” The usual interpretation of the story and its title (the image is from the Book of Revelations, and is referred to in the text by way of an “old spiritual”) is that Porter is condemning the devastating waste of WWI. But Miranda undergoes her own emblematic apocalypse: by experiencing her body as the enemy.

America’s authors have traditionally been reluctant to deal with the “horrors that nature inflicts on people.” We prefer to see nature as a means of rejuvenation rather than degradation. Are our writers going to chronicle the ways COVID-19 and the Climate Crisis will cut across our lives — create a Great Divide — as the 1918 pandemic did for Porter?

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of the Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and the Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created the Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Tagged: 1918 Pandemic, COVID-19, Influenza 1918, John O'Hara, Katharine Anne Porter, Pale Horse Pale Rider

A very interesting question. The only such writing on the subject that I can think of is “A Journal of the Plague Year” by Daniel Defoe, which is graphic in its details and actually has tables of fatality statistics.

Correction:

In the 1918 pandemic:

500 million people did get the flu. However, only 50 million world-wide died.

https://www.archives.gov/news/topics/flu-pandemic-1918Before COVID-19, the most severe pandemic in recent history was the 1918 influenza virus, often called “the Spanish Flu.” The virus infected roughly 500 million people—one-third of the world’s population—and caused 50 million deaths worldwide (double the number of deaths in World War I).

Best,

Daniel H.