Visual Arts Review: “Lucian Freud Self-Portraits” — Pictures of a Cool Narcissist

By Robert Israel

I recommend this show for Lucian Freud’s highly polished craftsmanship, but his wry game of psychological hide-and-seek is not all that satisfying.

Lucian Freud: The Self-Portraits, at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, through May 25.

Interior with Plant, Reflection Listening, (Self portrait), Lucian Freud, 1967. Photo: Courtesy of the MFA Boston.

Why is that bare-chested man cupping his ear? Why is he lurking behind leafy fronds?

Those and other unanswerable questions come to mind as you view the self-portraits of enigmatic British artist Lucian Freud (1922-2011) on canvas, paper, and etching plate, executed over a span of several decades.

The MFA is no stranger to self-portraiture: the museum has amassed a large collection of self-portraits by artists, dating from the 17th century to the present day, in many genres: paintings, sculptures, and etchings. But Freud’s work may be among the most enticing: in most of the 40 self-portraits, he takes on the role of the Artful Dodger, that cagey fellow from Charles Dickens’s novel Oliver Twist. Yes, the artist’s got skill. Yes, he’s cunning. But Freud eschews self-revelation; he only lets us catch glimpses of who he is. And while I recommend this show for his highly polished craftsmanship, Freud’s wry game of psychological hide-and-seek is not all that satisfying.

Scion of a famous family headed by psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud, Lucian and his kin (among them his first cousin, nonagenarian Sophie, emerita sociology professor at Boston’s Simmons College) paid visits to grandfather Sigmund on Sundays; they sat in silence because the good doctor was unable to speak (he was stricken with mouth cancer). According to Sophie’s memoir, the Freud clan, assimilated Jews all, escaped Germany as Hitler and his jackbooted murderers rose to power.

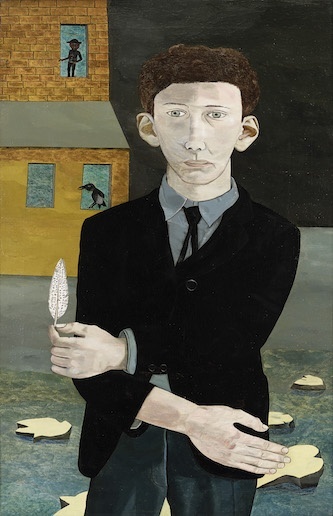

Lucian was 11 years old when his family arrived in England. In his first self-portrait as a young man, circa 1943, he’s a 21-year-old German-Jewish refugee: vulnerable, alone in a landscape populated by mysterious objects, holding a feather. This painting is among the most compelling here because we feel Freud’s alienation. And we wonder about that whisper-thin feather he holds aloft: will it help him survive migration and a war-wracked world?

Man with a Feather, Lucian Freud, 1943. Photo: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Freud’s best self-portraits – and there are a few — go beyond self-adoration. They demand our attention because they limn the transformation of aging, our common fate. In these we see the artist not only as he sees himself but, when he lets us in, he challenges us to see ourselves — warts and all. But other self-portraits are less accessible, to the point of becoming problematic. His work left me cold because he doesn’t venture beyond parading, even admiring, his own malaise.

Take, for example, his 1946 self-portrait titled Man with a Thistle, wherein he reveals himself to be a cocky urbanite, wearing a rakish open-neck shirt, sporting a mane of tousled brown hair. He personifies savoir faire. But, resting in the foreground, a sharp-edged plant admonishes the viewer: don’t get too close. Freud, like the thistle, is prickly. He’s intent on keeping us at bay.

This dearth of human warmth is highlighted eight years later in his painting Hotel Bedroom. Freud shows himself standing in the corner, enveloped in murky anonymity, an angry look on his face. Nearby, in the bed, under crisp white sheets, a clothed woman (identified as his wife) gazes at the ceiling, lost in the gloom of the rented room. Are they lovers? There is no suggestion of pre- or post-coital bliss. Lines from T.S. Eliot’s poem “Preludes” came to mind: “You lay upon your back and waited/You dozed, and watched the night revealing/The thousand sordid images/Of which your soul was constituted.” Initial critics of the painting accused Freud of being cruel, and that is a fair assessment.

Freud repeats this misogynistic motif again in Flora with Blue Toenails (2000-2001). Executed four decades after the hotel painting, the painting suggests the artist’s spectral presence via a dark smudge on a bedsheet upon which lies Flora, nackte Mädchen, a naked voluptuary, wisps of pubic hair peeking above her bare and bent legs. It’s a lurid scene. We witness this tableau as voyeurs, a role Freud relishes putting us in: he is a card-carrying Peeping Lucian. The swirling brush strokes that form the curves and heft of Flora’s bare breasts are in stark contrast to Freud’s menacing half-moon shadow, which soils the bedsheet as it approaches Flora. The painting anticipates a tryst; we expect Freud’s menacing perigee to achieve apogee once he sets down his palette and lets himself (and his shadow) engulf Flora.

Freud is a cool narcissist. His self-portraits are haunted, but not haunting. We can’t name his phantoms; he rarely invites that kind of involvement. He comes off as a phantom presence that won’t nestle beside the woman in the hotel room bed; a reflection on the surface of a puddle; a bare-chested man listening for sounds (his name?) while hiding behind the fronds of a plant. T.S. Eliot again, from his essay “Tradition and the Individual Talent”: “The more perfect the artist, the more completely separate in him will be the man who suffers and the mind which creates.”

Flora with Blue Toenails, Lucian Freud, 2000–2001. Photo: courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Here’s what I saw in the work of this “perfect” artist. Freud favors stark, bold brush strokes and applies a mix of bluish-grayish-white paint, a strategy that gives his models (including himself) the appearance of having been roughed up, bruised. He’s obsessed with his next conquest, dreaming about how he can use his paintbrush to grope naked models. Yet, paradoxically, Freud’s also clinical. Even when he dramatizes a lusty scene and its sensations of arousal, he embraces a safe, dominating ennui.

Robert Israel, a contributing writer since 2013, can be reached at risrael_97@yahoo.com.