Book Review: Vivian Gornick’s “Unfinished Business” — Remembrance of Pages Past

By Helen Epstein

Vivian Gornick is an elegist of the transformative experience of reading and writing, what she calls “the companionateness” of books.

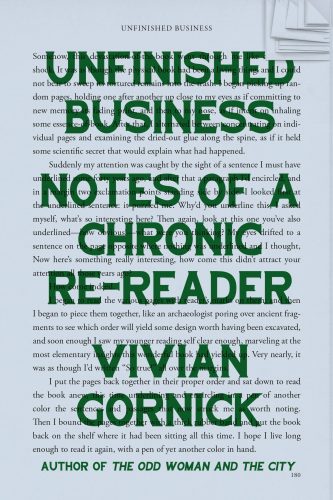

Unfinished Business: Notes of a Chronic Re-Reader by Vivian Gornick. FSG, 161 pp.

I always look forward to reading a new book by Vivian Gornick, the now 84-year-old journalist, essayist, memoirist, and literary critic who has been publishing her slim volumes of nonfiction for 50 years.

I always look forward to reading a new book by Vivian Gornick, the now 84-year-old journalist, essayist, memoirist, and literary critic who has been publishing her slim volumes of nonfiction for 50 years.

Gornick began writing for the Village Voice, in the late 1960s. Her first major piece of personal reportage was “The Next Great Moment in History Is Theirs” about a groundbreaking radical feminist group (including Kate Millett, Susan Brownmiller, Shulamith Firestone, and Ti-Grace Atkinson) in New York City. Her first book, In Search of Ali Mahmoud: An American Woman in Egypt, was published in 1973. I find her best-known book Fierce Attachments—about the lifelong love and struggle between herself and her mother—too raw and painful to reread, but I often dip into her other books for her point of view as much as for her distinctive voice. Whether reporting on others or herself or reviewing books, that voice—“angry, prickly, brilliant” (as she once characterized George Gissing)—is easily recognizable on the page. I’ve argued with Gornick’s journalistic methodology (she defends creating composite characters out of interviewees and rearranging sequence in nonfiction), but I’m an enthusiastic fan of her unique blend of memoir and literary criticism.

Unfinished Business: Notes of a Chronic Re-Reader is a collection of essays about what readers (using herself as case study) are ready and able to understand, over a period of years, of what authors write. Gornick acknowledges that she has written about and quoted from several authors in this book before; they have been her literary companions at successive stages in her adult life. They comprise a group that is as idiosyncratic as Gornick’s perspective: D.H. Lawrence, Thomas Hardy, and Delmore Schwartz, as well as Colette, Pat Barker, and Natalia Ginzburg. They are all writers interested in intimacy, loneliness, passion, and personal autonomy. If you’ve never heard Gornick’s own intimate, passionate voice, take a listen: “It has often been my experience that re-reading a book that was important to me at earlier times in my life is something like lying on the analyst’s couch. The narrative I have had by heart for years is suddenly being called into alarming question. It seems that I’ve misremembered quite a lot about this or that character or this or that plot turn … and I can’t help marveling, If I got this wrong, and this and this wrong, how come the book still has me in its grip?”

Gornick is an elegist of the transformative experience of reading and writing, and what she calls, “the companionateness” of books. “Nothing can match it,” she writes with a religious conviction. “It’s the longing for coherence inscribed in the work—that extraordinary attempt at shaping the inchoate through words—it brings peace and excitement, comfort and consolation. But above all, it’s the sheer relief from the chaos in the head that reading delivers. Sometimes I think it alone provides me with courage for life, and has from earliest childhood.”

She was 20-year-old English major at New York’s City College—and it was the mid-1950s—when she was first assigned to read Lawrence’s Sons and Lovers; over the next 15 years she would identify with a different major character—Paul Morel, his mother, or his lovers—each time she subsequently read it. It is difficult in 2020 to describe the impact Lawrence and his work had on several generations of 20th-century readers. Sons and Lovers was dated when I was assigned to read it in 1970, let alone in 2020. But Gornick seems to take for granted that her younger readers will be as captivated by his work as she was on repeated readings. She’s not inclined to widen her intense narrow focus on text and self and dive into an examination of the cultural and social contexts in which his novels were written and read. As a result, this chapter reads a bit like a museum piece.

Spending time with radical feminists transformed literature for Gornick. She writes, “Taking up many of the books I’d grown up with, I saw for the first time that most of the female characters in them were stick figures devoid of flesh and blood, there only to thwart or advance the fortunes of the protagonist whom I only just then realized was almost always male.”

Most male literary critics who have written books about reading rarely examine the work of more than a couple of women authors and, in this regard, Gornick shines a light on a wide-ranging group, including Colette, Marguerite Duras, Elizabeth Bowen, Pat Barker, and Natalia Ginzburg. Whether upbraiding Colette, finally understanding Bowen, or eulogizing Ginzburg, her observations about the work of women writers are almost all insightful, generous, and provocative.

Her best chapter, I think, is about 20th-century Italian author Natalia Ginzburg. Her work, Gornick notes, seemed written directly for her and helped her become “the writer I had in me to be.”

Gornick credits Ginzburg with helping her understand that while in fiction “a cast of characters is put to work, some of whom speak for the author, some against. Allow them all their say and the writer achieves a dynamic. In non-fiction the writer has only one’s own unsurrogated self to work with… Inevitably, the piece builds only when the narrator is involved not in confession but in self-investigation, self-implication actually.”

Gornick’s description of Ginzburg’s books and essays (that I had picked up several times in the past but not found intriguing—“Ah receptivity! Otherwise known as readiness,” Gornick writes) was so compelling that I drove to my local library and borrowed all of them. Gornick also reminded me why I loved British novelist Pat Barker’s sensitive and pain-filled writing about the aftereffects of the First World War, and that prompted me to search for a less-known author and book I’d never heard of: J.L. Carr and his A Month in the Country.

At 161 pages, Unfinished Business is short, like many of Gornick’s other books. It’s a rewarding read, but as always when I finish one of Gornick’s books, it left me wishing for more from this forthcoming, but ultimately very private, journalist.

Helen Epstein ‘s first book Children of the Holocaust in a new edition and her mother’s memoir Franci’s War will be published by Penguin in March.

Tagged: Culture Vulture, Unfinished Business: Notes of a Chronic Re-Reader