Opera Album Review: Oscar Wilde in the Opera House, Part 2 — Richard Flury’s Approachable “A Florentine Tragedy”

By Ralph P. Locke

Another operatic version of Oscar Wilde’s one-act love triangle that ends with the woman’s husband murdering her lover, to her enraptured delight.

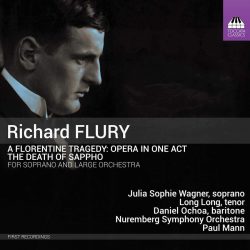

Richard Flury: A Florentine Tragedy and The Death of Sappho

Julia Sophie Wagner (Bianca); Long Long (Prince Guido Bardi); Daniel Ochoa (Simone).

Nuremberg Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Paul Mann.

Toccata Classics 0427–53 minutes.

Click here to buy.

Here is the second of two important operas to have been based on Oscar Wilde’s witty and sometimes bizarre one-act play A Florentine Tragedy. (For my review of Alexander von Zemlinsky’s setting, click here. I will shortly be reviewing here yet another Wilde-based opera, The Importance of Being Earnest, by Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco.)

Here is the second of two important operas to have been based on Oscar Wilde’s witty and sometimes bizarre one-act play A Florentine Tragedy. (For my review of Alexander von Zemlinsky’s setting, click here. I will shortly be reviewing here yet another Wilde-based opera, The Importance of Being Earnest, by Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco.)

I had never before encountered any music by Swiss composer Richard Flury (1896-1967). But I have seen mention of at least 11 CDs of his music, mostly instrumental chamber works. During his lifetime, his music was performed by such noted musicians as pianist Wilhelm Backhaus, violinist George Kulenkampff, and conductors Hermann Scherchen and Felix Weingartner. He dabbled in Hindemith-type modernism, but mostly wrote in a more traditional manner that led his works, as the 20th century went along (I hesitate to write “progressed”), to be sidelined as old-fashioned.

Here is Flury’s opera based on Oscar Wilde’s astonishing and relatively well-known one-act play A Florentine Tragedy, about a love triangle that ends with the woman’s husband murdering her lover, to her enraptured delight. (I once saw an effective production of it by high-school students!) Flury composed his setting in 1926-28, using a translation by Max Meyerfeld. He did not know that, a dozen or so years earlier, Alexander Zemlinsky had already composed an opera using the very same translation. Indeed, the booklet essay points out that two other (lesser-known) German composers wrote operas on the same Wilde play. This spate of settings was part of a trend in the decades around 1900: composers setting existing spoken dramas word for word, or perhaps with just a few nips and tucks. The most renowned instances are Debussy’s Pelléas (after Maeterlinck) and Richard Strauss’s Salome (after, yes, Wilde translated into German).

Zemlinsky’s setting has had a healthy career on disc: I am aware of at least five different recordings featuring such noted figures as mezzo-soprano Doris Soffel or conductor Riccardo Chailly. I have read particular praise of James Conlon’s recording, starring Deborah Voigt. I found the latest recording, which is conducted by Bertrand de Billy, intensely involving.

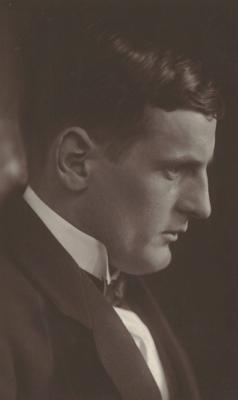

Composer Richard Flury in the 1920s.

I would love to see the Flury and the Zemlinsky settings on stage, one after the other. The composers’ styles differ drastically. Zemlinsky engages in near-constant chromaticism, though he varies the effect through frequent shifts in texture, tempo, and orchestral timbres. Flury’s musical language is more traditionally tonal and its vocal lines are more shapely. A noted critic remarked, after the premiere, that the music is marked by “luxuriantly beautiful, clear, unalloyed, honestly felt melody.” Think the Op. 10 songs of Richard Strauss or the operas of Erich Wolfgang Korngold (whose Das Wunder der Heliane I recently, and admiringly, reviewed here).

Still, Flury can get intense when the plot calls for it, which certainly happens as the relationship between the two men becomes more threatening toward the end. His rendering takes 43 minutes, whereas Zemlinsky’s takes some 10 minutes longer because of its greater emphasis on eeriness and dread and its tendency toward Wagnerian breadth.

The performances are very solid and idiomatic, displaying Flury’s abilities very well. All three singers sound quite idiomatic: it helps that the soprano and baritone are native German-speakers and that the tenor, though from China, spent two years at the Bavarian State Opera in Munich. Conductor Paul Mann, who has made numerous recordings with the Odense Symphony and other groups, nicely captures a wide range of moods across the work. The recording can be streamed through Spotify and other online services; excerpts can be heard on YouTube here and here.

On the CD, the opera is preceded by Flury’s 1928 setting of a condensed version of the title character’s final speech from the five-act tragedy Sappho (1818) by the great Austrian poet and playwright Franz Grillparzer. In these 40 lines (and 11 minutes) of rather free verse, the ancient poet Sappho bids a reflective, philosophical farewell to life, because the boatman Phaon has not returned her love, and then (though the booklet neglects to mention the crucial stage direction) throws herself off a cliff.

Flury’s setting (which can be heard in its entirety on YouTube) is sensitive to the flow and stresses of the verse, the melodic lines are shapely and expressive, and the orchestra supports and comforts the heroine in splendid fashion. Julia Sophie Wagner is, if anything, even better here than in the opera, conveying grandeur, nobility, and regret, all without becoming stentorian. She has made her career mostly in oratorios, lieder, and other concert works, rather than on the stage. I will now look for other of her (many) recordings.

The richly informative booklet essay is by Flury’s son Urs Joseph Flury, himself a composer.

Toccata Classics has been bringing out dozens of CDs devoted to stylistically conservative composers of the 20th century from many different countries. Flury is particularly deserving of this belated attention. Readers who wish to know more are directed to Chris Walton’s colorful and insightful book Richard Flury: The Life and Music of a Swiss Romantic (Toccata Press).

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines NewYorkArts.net, OperaToday.com, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in OxfordMusicOnline (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review is based on one that first appeared in American Record Guide; it appears here by kind permission.

Tagged: A Florentine Tragedy, Richard Flury, The Death of Sappho

[…] by Swiss composer Richard Flury – of more or less the same libretto that Zemlinsky used (likewise reviewed by me at […]

[…] And, for an intriguing comparison to Zemlinsky’s Eine florentinische Tragödie, Swiss composer Richard Flury’s less intense but still quite involving one-act opera (composed 1927-28) based on the same German translation of Oscar Wilde’s […]

[…] And, for an intriguing comparison to Zemlinsky’s Eine florentinische Tragödie, Swiss composer Richard Flury’s less intense but still quite involving one-act opera (composed 1927-28) based on the same German translation of Oscar Wilde’s […]