Book Review: The Holocaust’s Jewish Calendars — Protecting the Sacred Value of Time

By Susan Miron

Alan Rosen’s book thoughtfully illuminates the perilous calendrical devotion of Jews during the Holocaust, seeing it as a form of resistance.

The Holocaust’s Jewish Calendars: Keeping Time Sacred, Making Time Holy by Alan Rosen. Indiana University Press, 251 pages, $80 (hardback), $35 (paperback).

For two decades, I have assiduously avoided reviewing Holocaust books, having studied, written about, and immersed myself in the subject past the point of utter dejection. Then Alan Rosen’s new volume, The Holocaust’s Jewish Calendars: Keeping Time Sacred, Making Time Holy, arrived, and it completely captured my attention. Remarkably, there has been no other book dedicated to Jewish wartime calendars. Which is puzzling. Rosen’s important and very readable study raises and answers an array of significant questions concerning the concept and meaning of Jewish time as well as the value of a calendar’s insistence on normalcy, regularity, and order during the hellishly disordered time of the Shoah.

For two decades, I have assiduously avoided reviewing Holocaust books, having studied, written about, and immersed myself in the subject past the point of utter dejection. Then Alan Rosen’s new volume, The Holocaust’s Jewish Calendars: Keeping Time Sacred, Making Time Holy, arrived, and it completely captured my attention. Remarkably, there has been no other book dedicated to Jewish wartime calendars. Which is puzzling. Rosen’s important and very readable study raises and answers an array of significant questions concerning the concept and meaning of Jewish time as well as the value of a calendar’s insistence on normalcy, regularity, and order during the hellishly disordered time of the Shoah.

Rosen explains that the problem of losing track of time, thus being at a loss when it comes to observing sacred days, especially the Sabbath, is an old one. It is taken up in the Talmud, which discusses losing one’s way in the desert and eventually forgetting which day of the week it is. Why was it so crucial to maintain a semblance of Jewish time — even if only via a fragile handmade calendar? Why were people of all ages obsessed, wherever they were — in hiding, in ghettos, in labor and transit camps, finally in concentration camps? Rosen’s book thoughtfully illuminates this perilous calendrical devotion, seeing it as a form of resistance.

What does one mean by Jewish time? In an interview (Chabad.org), Rosen gives this response.

The Jewish day begins at night, at sundown. That means every day moves from darkness to light. Moving towards light has profound associations at any time. When dealing with a period of history as “dark” as the Holocaust, such symbolism surely carries even more weight. Also, the Jewish calendar is basically a lunar calendar, with every month beginning with the onset of the new moon and a full moon marking the middle of the month. So as one shrewd scholar of this period noted, even in Auschwitz, there was always a full moon — meaning that even those bereft of a Jewish calendar per se could by looking up at the nighttime sky roughly reckon the point of time in the Jewish month.

Rosen explores how the omnipresence of death and destruction inspired a creatively revised idea of time, continuity, the sacred and the mundane, the ordinary and the extraordinary. His focus on the Jewish calendar, the religion’s everyday symbol of continuity, sheds fresh light on how Jews continued to honor the power of time. As the availability of calendars diminished during the war, their importance grew, to the point that many believed Jewish life could not continue without them as reference points. The calendar also became a kind of elemental anchor for those who had become uprooted. The book’s focus is on an analysis of concrete artifacts — actual calendars — painstakingly produced by Jews who audaciously and courageously insisted that the Nazis could not expunge Judaism’s past — or its future.

In prewar times, a Jewish 354-day lunisolar calendar was a taken-for-granted aspect of Jewish life, marking time not only for institutions that were dedicated to religious life, but also for those living in secular and unaffiliated locations. As a point of reference, European Jewish culture used both the Jewish calendar and the civil one, defining events and experience along two parallel continuums. “One could be confident,” Rosen writes “that a Jewish calendar for the current year was nearby when needed.” Jews had a “multifaceted calendar consciousness, especially in Eastern Europe, whose Jews experienced the Holocaust by way of the Jewish calendar as well as the Gregorian or Julian. Wartime calendars and diaries that served as surrogate calendars help us understand the way Jews saw the world that imploded before their eyes.”

Rosen examined three dozen or so wartime calendars and draws moving portraits of their authors’ lives, along with detailing their creative construction of Jewish calendars in the bleakest of circumstances. Most calendars were made from scratch, others devised by writing in the blank spaces of already printed material, or by reusing a Polish Gregorian “Pocket Calendar Companion,” for the year 1939 (it was repurposed for the year 1944).

Layering the current Jewish calendar onto the outdated Gregorian one must have created for the author, and for anyone else that made use of the calendar, a unique, and certainly wrenching, template of time. The interwoven calendars meant living in two time zones simultaneously: before the war and during it, a time when Polish Jewry was still more or less intact and a time when it was in the very midst of its murderous undoing. The two frames of reference nearly, though not completely, span Polish Jewry’s devastating ordeal.… The fewer and thus more isolated the Jews were, the more desperate the desire to use whatever means at one’s disposal, no matter how imperfect, to have at hand a Jewish calendar.

Rosen explains further in an interview: “We don’t know who it was that adapted the Polish ‘Kodak’ calendar and substituted, as it were, the names of Jewish months, Jewish fast days and holidays, Rosh Chodesh (the beginning of the month) and the weekly Torah portion. We do know it took incredible vision, imagination and practical acumen to render such a transformation on this seemingly inhospitable ‘material.’ This unique Jewish calendar, a calendar of exile, was somehow wedged into a dated map of foreign time.”

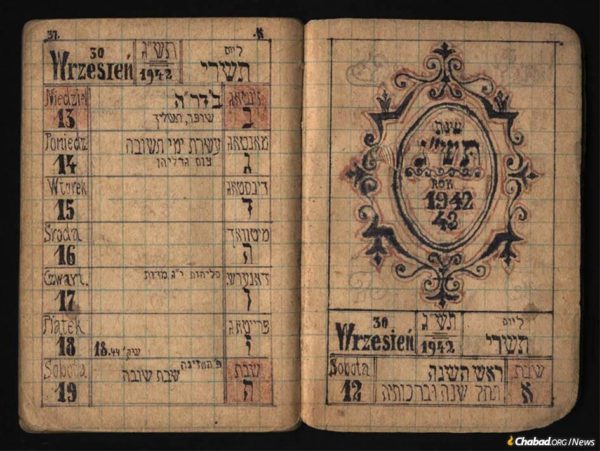

In early 1943, after two months of hiding in the forest, Rabbi Shlomo Yisrael Scheiner, a Chassid of Neustadt, his wife and their four children took refuge for the duration of the war in the house of a courageous employee, Franciszek Matjas, in Dombrova, Poland. While in hiding, the family busied themselves with basic survival and the study of Torah, the latter of which included Rabbi Scheiner preparing beautifully calligraphed calendars for the years 5703 (1942-43) and 5704 (1943-44). (Courtesy of the Scheiner family).

One of the most unusual Jewish calendars was undertaken by an Italian priest from September 1943 to July 1944, a period in which he sheltered seven Italian Jews. His extraordinary generosity extended to devising a calendar which aimed to set the correct date so that his guests could celebrate Passover. This important springtime holiday appears in the calendar of Sophie Sohlberg (the only calendar maker Rosen gets to meet). The Germans timed the actual deportation to Auschwitz to coincide with Hitler’s birthday on April 20. But Sophie and the other deportees, Rosen writes, lived according to a different calendar, conducting a Passover seder in the railway car — “an animal wagon,” as she recalled it, “without windows.”

From the “years of extermination” (as historian Saul Friedlander called this era) nine concentration camp calendars are known to have survived. Holocaust-era diaries were also used to mark Jewish time. “Time there,” a well-known survivor Yechiel Dinur wrote, “is not like time here.” “Ironically, in situations where everyone was starving, the fast days were still listed, almost as if they could do the fasting.” In Auschwitz, calendars were carved or sketched on prison block walls. Admirable ingenuity was deployed to fashion a calendar in Buchenwald. Using yellow-lined paper (coloring said to have been salvaged from yellow cement sacks), a calendar by a Rabbi Avigdor was written entirely in Hebrew script, so that “time would not be drained of its Jewish look, feel, texture. It intimates a world, and all calendars within that world, redeemed by Jewish time.” Ironically, the Nazis were all too aware aware of the Jewish calendar; they often arranged for roundups and murderous actions to fall on important Jewish holidays.

Rosen believes that in places such as Terezin, making a calendar helped Jews envision a different sort of future: “To plot time’s course gave the Jews a key to freedom, destiny, and identity. These calendars had within themselves the secret of freedom, the pitched determination to refuse enslavement of the Jews’ innermost selves.”

Why this subject has been overlooked or ignored is perplexing given Rosen’s superb book. Has no other serious scholar looked at these magnificent documents? The Holocaust’s Jewish Calendars will undoubtedly enlarge our understanding of the indispensability of calendars, and the necessity of keeping time, during the Shoah.

This review is dedicated to Elie Wiesel, in whose classes Alan Rosen and I learned countless invaluable lessons that transcend time.

Susan Miron, a harpist, has been a book reviewer for over 30 years for a large variety of literary publications and newspapers. Her fields of expertise were East and Central European, Irish, and Israeli literature. Susan covers classical music for The Arts Fuse and The Boston Musical Intelligencer.

Beautiful review of a fascinating book — thank you, Susan.