Book Commentary: “La patria y la muerte” — Exposing Mexican “Greatness”

By Jeremy Ray Jewell

José Luis Trueba Lara’s anti-popularist history is the truest kind of people’s history.

La patria y la muerte: Los crímenes y horrores del nacionalismo mexicano, by José Luis Trueba Lara. Grijalbo

The rise of Mexico’s president Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (a.k.a. AMLO) in 2018 shocked the political order, triggering comparisons from his opposition to Maduro or Trump. Although he is now the ‘last man standing’ in the Latin American left, he isn’t immune to criticisms from his own camp. The EZLN have rejected his major infrastructure plans in the south of Mexico. His government’s “hugs not bullets” approach to corruption and crime stands in contrast to its military operations targeting migrants at the borders. The sincerity of his government’s investigations into the 43 students infamously ‘disappeared’ in 2014 has been called into question. And the asylum offered to the exiled Bolivian ex-president also inauspiciously aligns AMLO with another government accused of manipulating elections and clientelism.

The rise of Mexico’s president Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (a.k.a. AMLO) in 2018 shocked the political order, triggering comparisons from his opposition to Maduro or Trump. Although he is now the ‘last man standing’ in the Latin American left, he isn’t immune to criticisms from his own camp. The EZLN have rejected his major infrastructure plans in the south of Mexico. His government’s “hugs not bullets” approach to corruption and crime stands in contrast to its military operations targeting migrants at the borders. The sincerity of his government’s investigations into the 43 students infamously ‘disappeared’ in 2014 has been called into question. And the asylum offered to the exiled Bolivian ex-president also inauspiciously aligns AMLO with another government accused of manipulating elections and clientelism.

Meanwhile other obstacles facing AMLO include a looming recession and increased reliance on public-private cooperation regarding his administration’s projects. Yet his supporters continue to push forward, believing devoutly in greener pastures to come for those who possess the political will and vision. For what these populists have on their side is nothing less than history itself. As Obrador has proclaimed, his victory inaugurated a new, “Fourth Transformation” in Mexico’s great story. An invaluable key to this historical reference (and its manipulative partiality) can be found in José Luis Trueba Lara’s La patria y la muerte, a sharp work of revisionism that examines the popular history of Mexico. The title translates as “Homeland and Death: The Crimes and Horrors of Mexican Nationalism” and the volume examines the long-lived mantra “homeland or death!” It considers the two options soberly, and evaluates just what the proposed choice means. Homeland or death? The opposition turns out to be meaningless because the two concepts boil down to the same thing, regardless of the nationalist ideals and populist rhetoric that have come along.

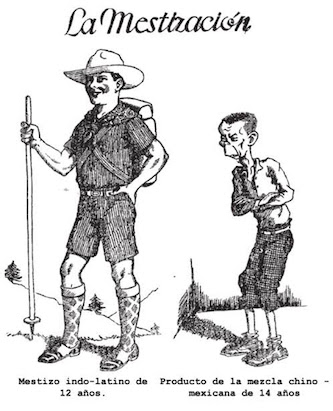

In contrast to the popular idea of a Mexico ‘beyond race,’ Trueba shows how the social constructs of the raza or the mestizo have always engendered virulent forms of racism. The modern category mestizo was invented during Mexico’s Independence (or “First Transformation”). For the first time, “differently colored people could be Mexican.” But the term, rooted in “the 1820s […] together with the first footprints of Romanticism and incipient European nationalism,” ended up encouraging the kinds of forced homogeneity seen in other nations. The results of this forced community went in two directions. On the one hand, new massacres and purges arose, new varieties of racism, violent reactions against indigenous tribes, Afro-Mexicans, and Chinese. There was also anti-Semitism, anti-Communism, and pro-Nazism. On the other hand, there were farcical projections of national types, from the idyllic ranchero to Greco-Roman Aztecs and airbrushed revolutionaries. Working in tandem, these two polarities have created a legacy whose destructive contradictions persist to this day. Xenophobia stands alongside a two-faced nationalism that reviles invaders while simultaneously replicating their prejudices. The héroe bandido somehow becomes an instrument of compensatory justice. The raza cósmica of José Vasconcelos is juxtaposed with “true” ethnic Mexican-ness and an imperative to “whiten.” Machismo marches astride a militant secularism. The list goes on.

“La mestización” by José Ángel Espinoza (1932). Top: “Mestization.” Bottom left: “Indo-Latino mestizo at 12 years,” Bottom Right: “Product of Chinese-Mexican mixing at 14 years.”

With that last example Trueba draws our attention to the so-called “Second Transformation” of Mexico: the War of Reform. Trueba sees the anti-clerical excesses of French Revolutionary Danton as the model. (He remarked that revolutionaries must “be terrible because the people cannot be.”) The removal of religion from the state in Mexico ended up producing social results that were odds with many of stated political intentions. For one, the banishment of faith from public life had a disproportionately demeaning effect on women, restricted as they were to the domain of private life. It also negatively impacted indigenous and poor communities of belief. Ironically, these were the very people who had earlier rallied behind the priest Hidalgo in the struggle for independence. The notion of a secular manhood appealed to hacendados and other wanna-be aristocrats. Like the erudite planters of the antebellum South, this upper class could sooner quote Xenophon than heed the warnings of a black Moses or the Virgin of Guadalupe. The elites, who operated the government, replaced the prelates as the people’s intermediaries when it came to articulating moral or ethical values. Meanwhile, “the power that the revolutionary deity evoked to operate miracles would require that the leaders have a code distinct from that which ruled the rest of the mortals.” As one honest politico later put it “morality is a tree that gives blackberries or serves for a fuck.” Thus was Mexico transformed again.

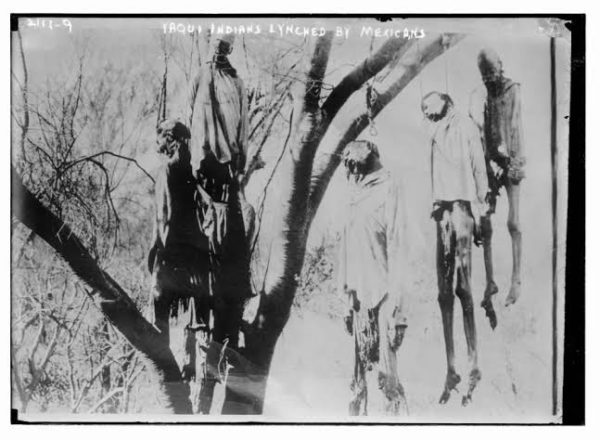

Few historical events are more fervently revered in Mexico today than its “Third Transformation,” its Revolution. The problem is determining exactly how and why the toppling of the Porfirio Díaz regime improved life in the country. As the saying goes, “the Revolution devours its children.” Although in Mexico revolutionary terror did not flow from republican virtue, as Robespierre would have it. The font of terror always sprang between those fighting for reform and the lethal vacuum of centralized authority. Revolutionary ideals set off a number of significant events, but they never became part of the ruling zeitgeist. What we can undoubtedly say about the Revolution is that it resulted in centrist reforms which tempered the expropriation of national resources by multinational corporations. It set Mexico on a course of social reform that it would gradually abandon in favor of market liberalization. It projected for the masses an elusive millenarian goal: the unrealized ideals of a revolutionary people. The Revolution became a perfectly empty canvas on which the people could project the hopes that its revolutionary leaders (once they were institutionalized) ended up crushing. Once the heroes of the Revolution were canonized and sterilized, the realities of their battle were omitted from public memory. Missing from school celebrations are the rampant rape, torture, and confiscations in the name of “the cause,” as are the starvation and mutilations. Pictures of bodies incinerated via gasoline, executed at firing walls, or hanging from poles or trees are nowhere to be seen. The Revolution kicked off 71 years of one-party rule.

But while the Revolution remains a blank slate, its greatest beneficiaries are less vague about its rewards. Luis Cabrera stated “revolution is revolution,” which Trueba remarks, “sounded good and that was good enough for him. Unlike the Bolsheviks, the victors of the massacre didn’t count on a precise utopia. The future still needed to be invented, even if — in the background – the revelation of the promised land already existed.” Indeed, it wasn’t the Bolsheviks who took power, it was Sonorans, or roughly speaking it was Sonoran men of means who had coalesced around Madero (who served as the 33rd president of Mexico from 1911 until shortly before his assassination in 1913). Despite the rhetoric, this was essentially a pragmatic revolution, and pragmatic norteños, victors of the Yaqui Wars, knew how to handle that. They were, after all, the embodiment of the 19th century Mexican, “willing to live in the most remote and inhospitable regions.” They knew how to deal with their locals.

The northern hacendado Venustiano Carranza ordered his general, Pancho Villla, to Saltillo in 1914 for the sake of distraction. The purpose was to keep the Villistas and their demands for land reform out of the capital. It backfired, causing Villa and Zapata to unite against Carranza. It was at this time that Villa, given his homicidal hatred of the Spanish and Chinese, would lament that Carranza had sold out his country — and the future of the mestizo race — to Yankees, technocrats [“científicos”], and Jews (never mind the assistance Villa had and would accept from America and Hollywood). Considerable revolutionary opinion regarded non-Catholics, displaced and stateless persons, or any other immigrants as responsible for “opening the door” to foreign interference and domination. Trueba points out the consequences: “between 1910 and 1919 1.27% of the foreigners living in Mexico were assassinated, and — in absolute numbers — the first places in the cemetery went to gringos, Chinese, and Spanish.” Gringo journalist John Reed famously rode with Villa while another, Ambrose Bierce, showed up the next year and simply vanished. Like just about anything that came across Villa’s path, much was left up to the caprices of those who were “revolutionized.” The long-standing Sephardi presence in Mexico made for an easy target; they had long been regarded as Spanish merchants. The Revolution didn’t inhibit stirring the mud of hatred.

“Yaqui Indians Lynched by Mexicans,” Library of Congress.

When the revolutionary Álvaro Obregón became president (1920-1924) he attempted to please Washington by appearing sympathetic to the plight of European Jews (although the US was closing its doors to refugees at the time). He welcomed approximately 30,000 Jews to Mexico. They quickly took advantage of the opportunities available to them, taking prominent roles in commerce and land proprietorship. Their presence became a sore spot for many Mexicans. During the height of the Great Depression there were attacks on Jewish and Chinese businesses. (250 Jewish merchants were expelled from a market in Mexico City in the name of protecting mestizo dominance.) More hostile actions followed, supported by the passing of anti-Semitic and xenophobic laws. The expulsion and appropriation of non-mestizo businesses became the order of the day. Mexican Jews forced to flee would never recuperate their losses. An organization of industrialists publically called on Mexicans to follow the example of Adolf Hitler. The arrival of Trotsky to Mexico exacerbated these trends. Sinarquistas, camisas doradas (Goldshirts, the Mexican version of Germany’s Brownshirts) and the Mexican Fascist Party agitated against Communists, capitalists, and minorities. Pro-Nazi publications circulated in substantial numbers, passing among brown mestizo hands. Trueba is unequivocal regarding Mexico’s role: “When Jews began fleeing totalitarian regimes, Mexico nearly closed its doors […] To close the borders and to restrict immigration to a drip implied support for the Holocaust.”

Mexican neo-Nazi Salvador Borrego, who died in 2018, would likely have been in agreement with the need to maintain stainlessness. His Derrota Mundial, published in 1953, argued that the defeat of Nazism was a “global defeat.” Eugenics, homogeneity, fascism — the “homeland,” in essence — had failed. What was left but death — of racial purity, of identity, of nationalism. But does the choice between “homeland” and “death” have any real value? Particularly when, as Trueba argues, it depends on a vision of history infused with strategic amnesia. When populist sentiments run high, the righteousness of their cause is often fueled by false depictions of the past. This analysis is not inherently partisan: in the age of “bad hombres” one could easily imagine applying it to Trump’s America as well as to today’s Mexico. La patria y la muerte asks us to consider Ukraine and its populist distortion of historical memory: “In Ukraine the memory of the Holocaust is almost completely repressed, the nationalist fury that turned the Nazis into heroes turned it into a blank page. The fight against Stalinism and its horrors was more than enough to disrupt that part of the past.” In other words, where there’s no public attempt to remember any atrocities, either Babi Yar or Katyn, then the present, without historical weight, becomes purely ideological and dangerously capricious. In this regard, Trueba’s anti-popularist history is the truest kind of people’s history. Learning about the past, no matter how unflattering, is a means of empowerment. The first step is to reject the false choice between “homeland” and “death.”

Jeremy Ray Jewell hails from Jacksonville, Florida. He has an MA in History of Ideas from Birkbeck College, University of London, and a BA in Philosophy from the University of Massachusetts Boston. His website is www.jeremyrayjewell.com, and he sometimes maintains a blog entitled That’s Not Southern Gothic.

Tagged: fascism, Jeremy Ray Jewell, José Luis Trueba Lara, La patria y la muerte, Mexican anti-Semitism

Muy buen artículo y excelente su documentación .

Él autor nos muestra las transformaciones que ha vivido Mexico