Book Review: “Klotsvog” — Confusion Reigns Supreme

By Lucas Spiro

Klotsvog ends up being a fascinating literary failure. Good for academics, but bad for readers.

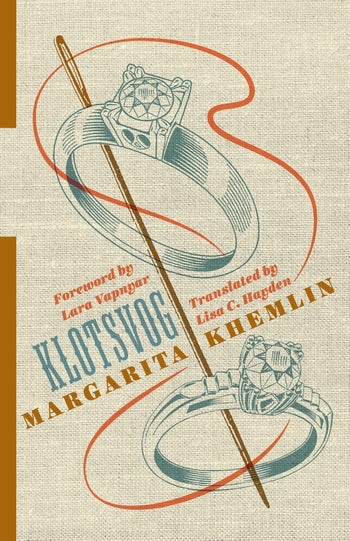

Klotsvog by Margarita Khemlin. Translated from the Russian by Lisa C. Hayden. Columbia University Press, 272 pages, $15.95.

Columbia University Press’s Russian Library series is known for producing demanding titles. However, I can’t remember being challenged in quite the same way by any of the other entries as I was by Margarita Khemlin’s novel Klotsvog, released in translation earlier this year. The book is billed as “about being Jewish in the Soviet Union and the historical trauma of World War II,” and “a novel about the petty dramas and demons of one wonderfully vain women.” That “wonderfully vain woman,” Maya, narrates the novel in the first person, and her voice is incredibly exasperating and unsympathetic. Klotsvog will probably be the first opportunity for English readers to engage with Khemlin’s work—she is a celebrated writer in post-Soviet Russia—and I’m afraid it might well be their last. There is inevitably loss amid gain in any translation, and I don’t read Russian, but my sense is that something essential was lost this time around. Klotsvog ends up being a fascinating literary failure. Good for academics, but bad for readers.

I can only assume that translator Lisa Hayden, who has a “reputation as an exceptionally thoughtful translator,” bit off more than she could chew in trying to render the peculiar strangeness of Maya’s first-person narration into recognizable English. One has to admire the undertaking, though. Capturing Khemlin’s mix of “skaz technique, mimicking oral speech in written form” along with Maya’s attempts to mix in mishandled elevated speech with Soviet bureaucrat-ese is probably difficult to read in the original. In addition, as Lara Vapnyar writes in the foreword, “Maya is confused herself.” She is not your conventional unreliable narrator because “unreliable narrators are there to confuse the reader,” explains Vapnyar. Psychologically, Maya cannot distinguish between reality and her interpretation of it. Culture, history, family relations, politics, and work are all filtered through her fractured and traumatized identity. This injects a heavy dose of tragic irony into a very modern story.

From the outset, the reader is wary of Maya’s curious use of language, the peculiar details she notices, or deliberately omits, and the lurching way she organizes her thoughts.

“My first name is Maya. Patronymic Abramovna, maiden name Klotsvog.”

“My surname’s very unusual, but I don’t know its literal meaning. If anybody knows, please tell me. It’s not important to me, though, because what’s important is how somebody made life’s journey, not what their surname is.”

Maya attempts to authoritatively rehash the confessional style of Dostoyevsky’s narrator in “Notes from the Underground,” but with significant departures. She insists on the bare facts of her name as if they are data points in a set that ought to explain something. But this is undercut by the admission that her name is unusual (according to who?) and that it’s not important anyway. But opening her story by making an authoritative declaration and then immediately undermining it doesn’t erode our confidence in her as a narrator so much as tip us off that we are dealing with a character with an eroded sense of self.

She goes on: “Field of work: mathematics teacher. Retired, of course. But I don’t consider myself a former teacher. Like a lot of other professions, a teacher’s profession doesn’t exist in the past tense. Acknowledging that sustains me tremendously.” She may be a certified teacher, but Maya never once works as an educator or, to use her term for herself, a “pedagogue.” If she uses her training for anything, it’s to manipulate and abuse a series of husbands and lovers, her two children who want nothing to do with her, and her extended family, which grows larger with each new marriage.

Author Margarita Khemlin. Photo: Wiki Commons

Maya approaches working as a “pedagogue” when she takes a job at “a primary school institution for mentally retarded children in the same location (though on the second floor)” as her daughter’s school. This is an attempt to become closer to her daughter Ellochka, who she thinks is fat, stupid, and mean, but Maya brags to others about how beautiful and intelligent she is. Ellochka is not a good student, but that probably is the burden of being Maya’s daughter. Maya’s son has successfully distanced himself from mom by showing interest in their Jewish heritage, which Maya tries to downplay. He has joined the navy as a submariner, literally submerging himself miles beneath the ocean. Ellochka’s means of escape is to engage in self-hating anti-Semitism — it is her way of coping with her confused sense of self. Ellochka pretends she is adopted and has been abused. Her teacher explains that “the children in class know and pity Ellochka. And give her extra food. An apple from one, a pastry from another.”

Any parent knows that showing up at your child’s school is guaranteed to push them away. Maya claims that she is savvy enough to see that the school “apprehensively offered” her the job, hoping she would decline, but not enough to foresee what was going to happen. “To her and her schoolmates,” Maya confesses, “I was a teacher for sick idiots and was thus partially an idiot myself, too. And, by the way, the so-called normal children spat just as well as the retarded ones – they expressed reciprocity at very high levels.” Maya’s ornery complexity is on full display here. Her language is harsh, yet what she claims the children do to her is undeserved, evoking a modicum of empathy. And she tries to knock the “normal” kids down a peg, which is admirable, but childish.

Klotsvog is the kind of novel that likely offers different interpretations with each read. Maya is a survivor of the Great Patriotic War, lived through the threat of Nazism, and lost members of her family to the violence of anti-Semitism. She manages to navigate the knotty Soviet system, maneuvering upward in society despite the fact that there are particular difficulties for Jews. Khemlin is out to create a frustrating yet fascinating character who is ultimately sympathetic because the circumstances of Maya’s life are expressed thematically and abstractly; not because she is likeable, but because she is pitiable. Maya does not have an inner life that invites understanding. She keeps her past traumas far from her conscious thoughts, making her stream-of-consciousness alienating. If you’ve met anyone who has experienced trauma, then you’ll recognize the mechanisms used to keep unpleasant or undesirable thoughts and experiences at bay. When the act of repression becomes that successful — an impregnable defensiveness that the narrator is unaware of — it is a difficult challenge for writer and reader. Translating that inner withdrawal into English from another language adds another layer of complication.

Still, Klotsvog‘s treatment of anti-Semitism intrigues. Hatred of Jews is expressed obliquely, pervasively, or by way of Ellochka’s intimate self-demeaning. Anti-Semitism is very much in the news today – ranging from the murder of 11 people by a right-wing extremist in Pittsburgh to absurd allegations of anti-Semitism against the Sanders campaign. Donald Trump is now trying to use Title IX to fight anti-Semitism on college campuses, even though it is nonsense to consider Judaism a nationality. In this context, engaging with unruly texts like Klotsvog makes sense. They don’t give us empathetic characters or satisfying reading experiences. But they do show us how hatred contorts — internally and externally — individuals and cultures.

Lucas Spiro is a writer living in Dublin.