Opera Review: Antonio Salieri’s “Tarare” — A Startling Opera of Social Commentary

Tarare is simply one of the most important operas of the Classic era, precisely because it challenges so many aspects of Classic-era “normality.” You won’t believe your ears.

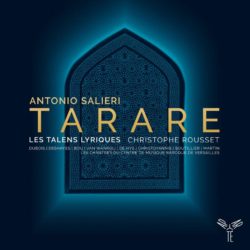

Antonio Salieri: Tarare (opera)

Karine Deshayes (Astasie), Judith van Wanroij (Spinette), Cyrille Dubois (Tarare), Enguerrand de Hys (Calpigi), Jean-Sébastien Bou (Atar), Tassis Christoyannis (Arthénée)

Les talens lyriques and Les chantres du Centre de musique baroque de Versailles, conducted by Christophe Rousset

Aparte 208 [3 CDs] 185 minutes

Click here to buy.

Salieri’s Tarare (1787) is without doubt the most daring and experimental opera written in the late decades of the 18th century. Salieri, working closely in Paris with his librettist, the renowned playwright Beaumarchais (author of the plays upon which Rossini’s Barber of Seville and Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro were based), created an opera that seems almost Lullyan in outward aspect (prologue and five acts, sung throughout, no spoken dialogue, and a prominent Act 3 divertissement). But, moment to moment, it consists mainly of brief exchanges among the cast members, avoids coloratura and repetitions of text, and rarely pauses for any solo statement longer than a short arioso (reflective, determined, or whatever). In all these ways, it anticipates by a half-century Wagner’s reform of opera. Seen another way, it boldly adopts, or invents anew, a musicodramatic technique from the earliest decades of opera (as manifested in the Orpheus-based operas of Peri, Caccini, and Monteverdi).

The opera was also daring politically. In the proto-Pirandellian prologue, Nature and the Spirit of Fire are seen almost flipping a coin to determine which of two, in a sense, unborn humans — in the opera we are to see — will turn out to be the heroic, low-born fighter for freedom and human rights and which will turn out to be the vicious tyrant. The clear implication is that rulers and commoners are very similar in their gifts and merits, and that rulers only end up in positions of power because of social privilege and its many advantages (what we nowadays too neutrally call “accidents of birth”).

The opera ends with an uprising by the people of Hormuz (a region near the Persian Gulf), who choose the army general Tarare to become their new ruler. The tyrannical Atar, despondent at having been overthrown by his own people, commits suicide before our eyes (another break with operatic tradition). The opera concludes with a moral, sung by everyone on stage: “Whether prince, Brahmin, or soldier: Man, your greatness on earth does not correspond to your [social] status but entirely to your character!” Two years later, the French Revolution would break out. The work, despite its many unusual features, was performed 131 times at the Opéra, the last being in 1826.

Soon after the premiere, Salieri heavily reworked the opera for Vienna, using an Italian adaptation by Lorenzo da Ponte of Beaumarchais’s libretto. Da Ponte removed the polemical prologue, toned down the criticism of hereditary aristocratic rule, and cranked up the comedy in some scenes. He also provided full-length aria texts for the main characters, which Salieri set to music that is full of relatively conventional coloratura but is nonetheless as fine, in its way, as whatever he chose to keep from the Paris Tarare. The Italian version changes some of the characters’ names and thus bears the title Axur, re d’Ormus. The work was widely performed in Vienna and beyond (e.g., in Warsaw).

Both versions have their merits. Axur received a capable recording on the Nuova Era label (used copies can still be found) conducted by René Clemencic. Tarare, the bolder, French-language work, can be viewed on an ArtHaus DVD, conducted by Jean-Claude Malgoire, with many skillful early-music singers. The production, acting, and dancing are marvelous, using in fresh and imaginative ways low-tech staging devices that might have been typical of the day.

Christophe Rousset & Les Talens Lyriques. Photo: Jacques Verrees.

But this is, to my knowledge, the first CD recording of Tarare. It was made over three days in two locations in Paris and its suburb Puteaux; at least one of those days involved a public performance, unstaged. The recording is a marvel, conducted by Rousset, one of today’s great early-music conductors. The orchestral sounds are tangy, the rhythms springy. Salieri’s instrumental parts often display a quicksilver inventiveness: for example, a short passage with staccato notes for bassoon or, in the Neapolitan singer Calpigi’s song about his earlier life and career, a perky flute obbligato, played here on a marvelous wooden instrument. Orchestra and chorus show generally excellent intonation.

The complete recording is available on streaming services such as Spotify and can be heard on YouTube broken down into many segments. Some highlights have been gathered in this video, along with comments from the conductor, Christophe Rousset.

The cast includes several of my favorite youngish French-born singers. I loved Karine Deshayes’s recordings of music by Félicien David and Rossini and Cyrille Dubois’s recordings of Berlioz, Félicien David (again), and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. On the equally marvelous (Dutch-born) Judith van Wanroij and (Greek-born) Tassis Christoyannis see my review of Gounod’s Le tribut de Zamora. Enguerrand de Hys is new to me: a character tenor perfect for the quick, sly connivings of Calpigi. Jean-Sébastien Bou, as King Atar, hectors when agitated, and his low notes are weak. (I mentioned his low-end problem in a review of the Lalo/Coquard La Jacquerie.) But, like all the others, he enunciates the text beautifully and with seemingly infinite nuances of intent. In short, the performance outdoes at many points the generally fine DVD and, even more, the Axur CD. Unless you can understand French sung at a conversational pace, I urge you to follow the libretto and translation closely as the music goes along.

The elegant hardcover book that comes with the recording contains a superb essay (by Salieri authority John A. Rice) and Beaumarchais’s brilliant, corrosive libretto. Everything is in French, English, and German. One annoyance: there are no track numbers in the lengthy libretto. One must therefore keep flipping back to the tracklist printed earlier in the book. The tracklist also does not indicate the page on which a track begins.

For further information about this amazing opera, including many specific indications for the singers (e.g., the tyrant must sing one phrase “disdainfully”), I urge readers to look at Rice’s 1998 book Antonio Salieri and Viennese Opera, or my 2015 book Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (pp. 301-7).

Tarare is simply one of the most important operas of the Classic era, precisely because it challenges so many aspects of Classic-era “normality.” You won’t believe your ears. Rousset’s amazing recording leaps onto my list of “best of 2019.”

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to the online arts-magazines NewYorkArts.net, OperaToday.com, and the Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in OxfordMusicOnline (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review is based on one that first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here by kind permission.

Tagged: Antonio Salieri, Aparte, Christophe Rousset, Les Talens Lyriques

So Salieri shouldn’t have been so jealous of Mozart …

Salieri was indeed a highly accomplished composer! He and Mozart may have been rivals but perhaps no more than any two composers working in the same place and vying for the same commissions. Salieri of course did not poison Mozart, as legend (and Pushkin) long had it. But in “Tarare” (1787) he composed an opera that boldly undid much of Mozart’s operatic legacy (and indeed his own legacy, in other operas). “Tarare” is an astounding work, and I’m thrilled (as I hope my review shows) that it has now received such a vivid, sometimes disturbing realization on CD. Alas, the trailer embedded in my review presents some of the more “normal” moments in the work (beautiful ones, I admit). This is an opera to be heard and read, libretto in hand.