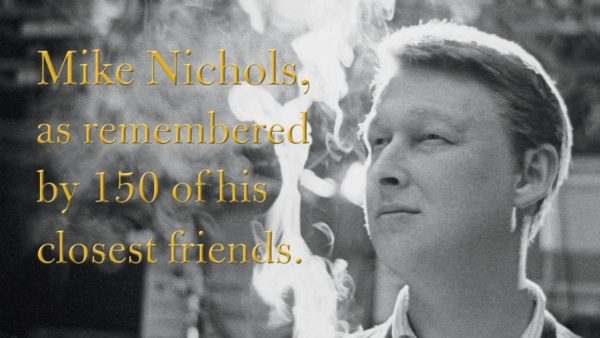

Book Review: “Life Isn’t Everything: Mike Nichols, as remembered by 150 of his Closest Friends” — A Frothy, Gossip-filled Bauble

By Helen Epstein

If you are a fan of Mike Nichols’s large and elegant body of work, you’ll regret as I did that the authors did not take the time to create the kind of book he deserved.

Life Isn’t Everything: Mike Nichols, as Remembered by 150 of His Closest Friends by Ash Carter and Sam Kashner. Henry Holt & Company, 368 pp., $30.

If you’re looking for a frothy, gossip-filled bauble of a gift for a theater-loving friend, Life Isn’t Everything may be it. Billed as an oral history, it has none of the heft or resonance of a Studs Terkel work. It reads more like notes for a Vanity Fair piece, with the better bits drawn from published books (The Richard Burton Diaries, playwright Jeffrey Sweet’s Something Wonderful Right Away: An Oral History of the Second City and the Compass Players), well-edited television shows (PBS’s American Masters), and other people’s research materials (John Lahr collection at Boston University). Some of its best quotes are culled from old interviews with comedy pros such as Steve Allen, Jules Feiffer, Bob Newhart, Woody Allen, and Steve Martin, sharing their first impressions of Nichols as a performer. The authors’ own interviews are markedly less interesting and more slapdash: quick takes on Mike Nichols from playwrights such as Tom Stoppard, David Hare, and David Rabe, and actors Dustin Hoffman, Christopher Walken, and Meryl Streep. There are many banal quotes from famous names. If you are a fan of Mike Nichols’s large and elegant body of work, you’ll regret as I did that the authors did not take the time to create the kind of book he deserved.

Life Isn’t Everything begins with a smattering of tributes from contemporaries (John Lahr: “He was prowess personified;” Cher: “For me, he was more than a director. He was always more than a director”), then follows a chronological structure, starting with Nichols’s early American life on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. Because dates are for the most part eschewed, I’m guessing that the first chapter covers 1939-1947 — there’s no hint that World War II has started or ended. Brother Robert Nichols, a physician and the most useful and reliable voice in the book, sketches the two brothers’ parents: Dr. Pavel Nikolaevich Peschkowsky, a Russian Jew who emigrated to Germany (unclear when), and Brigitte (we assume Landauer), orphaned before she was 12. Dr. Nichols describes her as a woman who was “what used to be called neurotic.” The four lived in a one-bedroom apartment at 155 West 71st Street; the father’s office was on the ground floor. Robert describes his father as unfaithful, his mother as difficult, and the illness that left his brother hairless as a young child as alopecia totalis universalis, “which means total baldness everywhere…. Our father, for some reason, did not want him to have a hairpiece…. Our father died in June of 1944, when he was forty-four. Mike was twelve.”

There are many more questions I would have asked Robert Nichols and the boys’ babysitter, Marianne Mosbach, who is briefly quoted. But Life Isn’t Everything then skips to the University of Chicago (no clue when or why Nichols chose it or whether he took any classes), where he falls in with a group of theater people. “There was very little indigenous Chicago theater,” recalls playwright Jeffrey Sweet, who describes the evolution of Playwrights Theater Club and The Compass Theater and their leaders. Together with young actors Barbara Harris and Ed Asner, Nichols performed in classics by Shakespeare, Chekhov, Cocteau, Ibsen, and Brecht, but soon met Elaine May and, as a result of a bar owner asking for a longer set, moved into Improv and to Greenwich Village.

“They asked for an opening line and a closing line,” recalls Jack Rollins, their manager for eight years. “Suddenly comedy was being formed right in front of my eyes and I mean comedy that was side-splitting and irresistible…. I fell in love with these two people immediately.” Tom Lehrer recalls sharing a bill with Nichols and May at The Blue Angel; Milton Berle recalls thinking, “I’ve never seen anything like it in my life.” Jules Feiffer recalls, “It was the first time a man and a woman – or a boy and a girl in a car – actually talked about having sex. It had never been done before. It was as ground-breaking as, say, The Graduate was some years later.”

Life Isn’t Everything added almost nothing to my understanding of the miraculous collaboration of Nichols and May. I just learned that in October of 1962 (one of the few actual dates cited) May directed Nichols in her play A Matter of Position and, according to John Lahr, “The play died and so, for a long time, did their relationship.” However, as a result of that rupture, Nichols became a director. The rest of the book (covering over 50 years) takes the reader through many of the director’s most interesting theater and movie projects in the manner of a travelogue — pleasurably but without much depth.

We visit theater productions of Neil Simon’s Barefoot in the Park and The Odd Couple; Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf; Tom Stoppard’s The Real Thing; David Rabe’s Hurly-Burly; Wallace Shawn’s The Designated Mourner; Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman; and the films The Graduate, Catch-22, Silkwood, Carnal Knowledge, Working Girl, The Birdcage, Charlie Wilson’s War, and Angels in America.

It’s a voyeur’s dream to read some of the things actors, writers, managers, and friends have to say about Nichols, even the most shallow. But if you’re a serious reader, interested in character, cultural context, and theater history, there’s a lot missing in this volume. Like so many new nonfiction books, Life Isn’t Everything needed a better editor and a fact-checker, to confirm both specific facts and speculations. One thread I found particularly irritating throughout the book was how Nichols’s dark, depressive side was attributed to his escaping the Holocaust. Maureen Dowd says, “He was a Noel Coward figure with a Jerzy Kosinski past.” In fact, Nichols (born in Berlin in 1931) did not wander through rural eastern Europe alone, but spent a few parentless days on a luxury liner crossing the Atlantic to New York City with his younger brother in 1939, supervised by an attendant. His actual childhood experiences in Berlin, his relationship to his family there and in New York, his schooling, his father’s premature death, his teenage relationships with friends — and whatever difficulties he had besides his alopecia — all go virtually unreported in this book, as do serious assessments of what made Nichols tick, how he selected his intimates, why he chose to live with the women he did. Missing are the voices of some of the people who knew Nichols best — collaborator Elaine May, his three ex-wives Patricia Scott, Margot Callas, and Annabel Davis-Goff, his children, and widow Diane Sawyer.

I found myself putting down the book at many junctures to look up people and productions and reviews on the internet – looking for the kind of material readily available in biographies. There are a few good photographs, but no production list and no information about the contributors. All in all, a hurried, careless job of a book. I was glad to read in Carter and Kashner’s Acknowledgments that a traditional biography is in the works. I’ll be an enthusiastic reader.

Helen Epstein is the author of Joe Papp: An American Life and nine other books of non-fiction. She has reviewed for The Arts Fuse since its inception. Most recently she edited Franci’s War,a memoir by her mother to be published by Penguin in March of 2020.