Rock Feature: Roger Daltrey of The Who — How Can He Afford to Tour?

By Blake Maddux

If there is any theme that runs throughout the story of Roger Daltrey’s life as he tells it, it’s that he has always needed more money to – as he so folksily puts it – “pay the bills.”

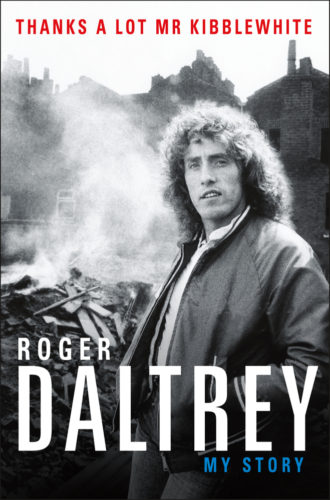

The Who will be performing at Fenway Park on Friday. After reading Roger Daltrey’s 2018 memoir, Thanks A Lot Mr. Kibblewhite (Henry Holt and Co.), I cannot help but wonder: how can one of the greatest lead singers in the history of rock ‘n’ roll afford to do this?

If there is any theme that runs throughout the story of Daltrey’s life as he tells it, it’s that he has always needed more money to – as he so folksily puts it – “pay the bills.”

Let me say off the top that I will not claim for a single second to understand the economics of touring. In documentaries, movies, etc., it is always depicted as the most lavish of all possible experiences.

Of course, the amount of money generated from a tour by one of rock’s most popular and enduring bands guarantees a feeding frenzy. It’s not like the band gets to divide the grosses equally among themselves. There are managers, lawyers, accountants, drivers, roadies, and myriad other hardworking, underpaid laborers whom I have unfairly excluded from this list.

As Daltrey describes it, “You have to understand what it’s like the day before you start a tour. . . . You’re in the hole to the tune of a few million quid. You’re as indebted as you ever want to be. You pay off the debt through the tour. . . . [O]nly in the last few shows of thirty or forty do you finally make it into the black. If you’re lucky.”

This passage appears at the point in the book at which Daltrey and Pete Townshend have decided to carry on after the sudden death of bassist John Entwistle on the eve of the band’s 2002 North American tour. This observation presumably applies to any point at which a band is about to hit the road, and the costs of doing so in 2019 are surely not fewer or lesser than they were in 2002.

But how can such a whopping pecuniary burden apply to The Who? This is a band that grossed more than $42 million from its 2012–2013 US/Europe tour and $26.5 million from the 28 dates of its 2016 North American trek. Is this a recent phenomenon, engendered by decreased album and merch sales?

According to Daltrey, no.

Here is how he remembers the end of The Who’s first American tour in 1967, which was also the year of their first US top 10 hit:

I wanted to come home with more than I’d gone out with so I’d limited myself to a strict diet of one hamburger a day and a few other tidbits. . . . [W]hen I got back I went to see . . . our agent to ask him for my share of the profits. ‘There aren’t any to share,’ he said, quite apologetically. . . . I’d hardly spent anything. And he said, yes, but do you know what Keith spent?

Daltrey is referring, of course, to Keith Moon, The Who’s legendarily obstreperous drummer, who was known to leave hotels — not just their rooms — in less pristine condition than they were in when he arrived.

“I had to borrow the money for my flight home,” Daltrey continues. “I went home skint.”

Fortunately, or “miraculously” as he puts it, Daltrey came home from the 1968 US tour with a bit of scratch: “Just enough for the deposit on a house . . . [and] a lovely old Mark 10 Jag.”

Cool, so surely they were in the black now, as the following year saw the release of Tommy – The Who’s first album to reach the American top 10 – and the band’s paying gig at Woodstock.

Nope, not so much.

“By the end of 1969,” Daltrey recalls, “we were the biggest rock band in the world. . . . And we were barely breaking even. . . . We were spending it faster than we could earn it. . . . It was all going to the tours. . . . It was obvious that the more we toured the more we owed. So we decided to stop.”

As for Woodstock, “We needed the cash to get home and pay the bills, so we refused to go on until we were paid.” The $6,250 ($42,000 and change today) that they received made them only the 10th-highest-paid of the festival’s 32 performers. (And their set was probably the longest.)

Daltrey remembers that in 1971, when The Who scored back-to-back top 5 albums with Who’s Next and Live At Leeds, their accountant “was pleased to tell us that we were only six hundred thousand pounds in debt.”

Thankfully, the cash-strapped rocker and his wife were able to purchase a £39,500 house because a bank was willing to extend him credit on the assumption that he was a multimillionaire.

It would be a few more years before Roger and his mates became wise to the fact that much of the dough was subsidizing a mutual vice of Moon and manager Kit Lambert. Daltrey had long suspected such misappropriation of funds, but Townshend wasn’t all that cheesed off until he “found out they’d been at his publishing money as well.”

There were also external forces at work that were beyond the band’s control. Daltrey does a fine job of weaving British social and political history in and out of his life’s narrative, such as when he explains that “This was 1975 — the height of socialist Britain. Harold Wilson was prime minister again, top earners were paying 98 percent tax, and all the bands were going into exile (we were one of the very few that stayed).”

Townshend rarely felt the bite of Moon’s misbehavior, Lambert’s mismanagement, or the government’s rapacity. He owned the copyrights to all of The Who’s profitable songs. Therefore, in Daltrey’s words, “cash from gigs was just pocket money for him,” but he himself “couldn’t sit on [his] arse and live off royalties.”

As for that notorious drummer, “He had bought the beach house next door to Steve McQueen in the Colony, the most expensive part of Malibu. . . . He had no money and any money he could get his hands on, he was spending. When we refused to give him any more cash, he borrowed ten thousand dollars from our agent.”

Roger Daltrey in May 2016. Photo: Wiki Commons.

Surprisingly enough, it was when Daltrey began to work outside of The Who that the pounds finally started to pile up. His eponymous 1973 solo album “sold better than any of the earlier Who singles albums.” He “started making money like [he] never had before” under new management. When the band broke up in 1983, he still “had to pay the bills. So the eighties became about acting, solo albums, and fish farming.”

Eventually, of course, “financial necessity drove us back.” Not only did the singer, incredulously, need some bread, but so did the bassist.

“John Entwistle started to run out of money by the end of the eighties. For that matter, so did I. It’s expensive living the life of a rock star when you’re not earning rock star money.”

And Entwistle lived the life of a rock star possibly more than either of his colleagues: “Even a two-million-dollar gig in Vegas wouldn’t keep him going for long. He lived like Elvis and it never seemed to bother him that he didn’t have the income of Elvis.”

Daltrey’s ostensible financial woes continued into the ’90s and the new millennium. The 1994 Daltrey Sings Townhend tour included “the fastest sell-out in [Carnegie Hall’s ] 103-year history,” but left him “down a million bucks.” The 1996–1997 Quadrophenia tour with Townshend “made a few quid from the US shows but . . . we came back from Europe with the princely sum of sixteen thousand pounds.” It was great news to Daltrey when Townshend agreed to do another Who tour in 2002 because, sure enough, he “needed the cash and John needed the cash.” Entwistle, sadly, wouldn’t be around long enough to earn — let along spend — any of the spoils.

Happily, this thorough account of ongoing financial hardship ends on a positive note. The 2006–2007 tour in support of the first Who album in 24 years “broke even.” After 50 years, Daltrey can happily report, “We now tour at the very height of luxury. Posh hotels, private jets, gold taps, and marble, bloody marble.”

Maybe, at long last, this lifelong member of a band that has sold tens of millions of albums is no longer struggling to keep the debt collectors at bay. (And will treat himself to more than one hamburger when he is in town this weekend.)

Blake Maddux is a freelance journalist who regularly contributes to the Arts Fuse, the Somerville Times, and the Beverly Citizen. He has also written for DigBoston, the ARTery, Lynn Happens, the Providence Journal, The Onion’s A.V. Club, and the Columbus Dispatch. A native Ohioan, he moved to Boston in 2002 and currently lives with his wife and one-year-old twins–Elliot Samuel and Xander Jackson–in Salem, Massachusetts.

Great article on a great man. I’ve crushed on Roger for years and finally got to meet him in the late ’90s.

SOOO lucky.

I have a BUGE crush on Roger Daltry….the way be was years ago and today.

He is without doubt one of the sexiest most talented man in the world.

It was Roger who had The Who’s hot shot managers, Stamp and Lambert, fired after he ordered an audit. (Pete Ham should have taken notes.)

The Who’s break with Talmy also cost them money.

But, Roger should have seriously questioned why the band was paying for Moon’s criminal and incredibly immature behavior, if what he says is true.

Moon and Entwistle were immature spending machines. And both were pretty much unable to make money outside The Who.

Two pretty sad and pathetic human beings. But, perhaps, the greatest rock & roll rhythm section ever.