Book Review: “Exposed” — Between Two Incompatible Worlds

By Peter Walsh

Jean-Philppe Blondel’s books are especially praised by critics for their charm and smoothly shaped prose.

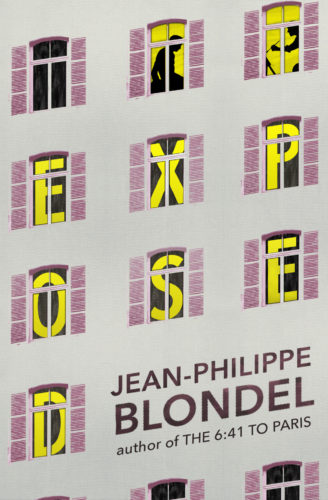

Exposed by Jean-Philppe Blondel. Translated from the French by Alison Anderson. New Vessel Press, 157 pages, $16.95.

Jean-Philippe Blondel is a French writer and author of a string of novels, many of them written for young adult readers. His best-known work for adults was published in English as The 6:41 to Paris (New Vessel Press), about a pair of ex-lovers who encounter each other on a train after several decades. Blondel’s books are especially praised by critics for their charm and smoothly shaped prose. Both virtues are evident in Exposed (French title La Mise a nu) in an English translation by Alison Anderson. At just over 150 pages, it is an easy and pleasant read.

Both Blondel’s protagonist and his archetypal plot are fixtures in modern literature (see Herman Hesse’s Steppenwolf, Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice): an aging loner with introspective and intellectual tendencies — world-weary, bored, and blocked — embarks on an unexpected adventure that might be erotic. Or dangerous. Or both.

Blondel’s narrator, Louis Claret, divorced and living by himself in a cramped apartment in his native cathedral town, somewhere in France, has taught English in a local high school for more than 35 years. Now 58 and nearing retirement, his profession no longer holds much of a thrill, although he was apparently once a dedicated and well-liked teacher. His two grown daughters keep in touch but live far away. Louis worries that they have transferred their deepest affections to his ex- wife’s new partner.

Otherwise, life is pretty uneventful: “My horizons have expanded but my life has shrunk.” Much of his spare time is spent alone, sorting through decades-old memories. “Memories drawing a path across the earth,” he thinks. “Sometimes, one of these coils of memory becomes more luminous than others. Almost phosphorescent. A glowworm in a graveyard of memories.”

Like the Hesse and Mann’s volumes, Exposed seems to draw on deep autobiographical sources. Born in Troyes, an ancient city of about 60,000 in eastern France, Blondel, now in his 50s, has taught English for many years at a high school in a nearby town. In all three novels, the protagonist serves as a mask — a way for the author to express his own reflections on life.

Louis’s Adventure comes in the form of a former high school student, Alexandre Laudin, now in his 30s. Although Louis barely remembers him as a pupil, Alexandre has become a famous artist whose career Louis has followed from afar: the painter’s photograph appears on the cover of art magazines. His former student is regularly in the news and appears to live a glamorous life, traveling between exhibitions in art capitals around the world. Laudin lives, in short, the sort of life that Louis does not, in the sort of trendy Paris neighborhood where, Louis muses, “the pulse of life beats faster.”

Alexandre surprises Louis by seeking him out at the opening of a retrospective exhibition in his native town. Louis apparently made a greater impression on the young Alexandre than the other way around. Alexandre asks to meet at a local restaurant. It develops that he wants Louis to pose for him, also that he keeps a pied à terre and studio nearby, a location perfect for their sessions. With some reluctance Louis, who realizes the project could make his image famous and perhaps publicly embarrass him, agrees. As the project progresses, he comes to realize that he will be asked to expose more and more.

Louis claims, on the novel’s first page, that he “has not spent much time in the world of visual arts.” Alexandre’s is only the second exhibition opening he has attended in his entire life. Nevertheless, Louis — or Blondel speaking through him — speaks intelligently about Lucien Freud, Munch, Francis Bacon, David Hockney, even Bernard Buffet, all as Alexandre’s influences.

Still, the book doesn’t seem to be that much about art. To be sure, the act of painting does not translate well into fiction or film. Outside of the artist’s head, the process consists mostly of making strokes on a canvas, observing the results, and adding more strokes. Instead, the rarefied (at least as Louis sees it) art world sets up a chasm between Alexandre’s elite life and his own mundane one. The paintings serve as a dramatic device, a foil to develop the relationship between the two main characters. Alexandre encourages conversation while he works, and likes a dialogue that is both casual and revealing. “[L]et me suck the blood out of your soul,” he tells his subject. “It will be my revenge and my tribute. Would you like a beer?”

Through authorial intent or the accidents of 21st-century globalization, both Blondel’s setting and his characters’ everyday lives are oddly generic. People eat from Chinese and Italian buffets in chain restaurants in shopping malls. Louis’s town has bypasses, decaying playgrounds, and deserted parking lots scattered with abandoned shopping carts. Whole families dine out while staring at their smart phones. Louis and his ex-wife Anne drive around aimlessly while listening to an oldies station. Newly single, Anne, goes running, takes up painting, becomes an environmental activist, and acquires a cool new boyfriend. Louis’s daughter Skypes him from Montreal and tells him to “get out and do things.”

Author Jean-Philippe Blondel

To anyone familiar with French provincial life, the context, even from Blondel’s bare bones descriptions, is instantly recognizable: a small city in a nation where a famous and glamorous capital has, for many generations, drained away most of the talent and energy, and much of the significance, from the rest of the country. But, to many other readers, the place might just as well be in Ohio, the British Midlands, or in western Bavaria. Only a few details — the names of French secondary school grades, a toy dog in a restaurant, a mention of Edith Piaf — mark the setting as specifically France.

This dearth of local color, combined with the beige tones of Louis’s life, give the narrative a strange, monochrome vibe. The sharp, particular hues of place and person have all been bleached out — as if by some EU regulation. The plot, which contains nothing as dramatic or final as found in Steppenwolf or Death in Venice, moves along nicely, though, largely on the quality of Blondel’s prose, enlivened by a muted but persistent sexual tension. The narrative is shaped conventionally: there is character development, an unfolding narrative, some flashbacks, and a climax, followed by a denouement, which, when it finally comes, turns out to be a repeat of a youthful peak experience remembered earlier in the narrative.

The concluding epiphany is optimistic but unconvincing. Louis, who makes it clear he is not one to step far out of his comfort zone for long, remains stuck in a life that is essentially bleak. Yet he regrets its ordinariness, its unplanned path, the “litany of surprises life has in store.” “I hadn’t planned to stay rooted in this provincial town,” he explains. “Or to become a dinosaur where I teach. Or to have daughters. Or for them to get old. Or for them to go away. Or to divorce.” Alexandre, on the other hand, seems destined to move on in a career full of anxiety and uncertainly.

At its end, the novel seems to represent two, unreconcilable sides of Blondel’s own life: Louis represents his ordinary side as a small town teacher, Alexandre suggests the glamorous world of celebrity and international travel the success of his books have brought him. It seems, in a world ground into conformity, a depressing choice between two incompatible, ultimately claustrophobic worlds.

Peter Walsh has worked as a staff member or consultant to such museums as the Harvard Art Museums, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Davis Museum at Wellesley College, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, and the Boston Athenaeum. As an art historian and media scholar, he has lectured in Boston, New York, Chicago, Toronto, San Francisco, London, and Milan, among other cities and has presented papers at MIT eight times. He has published in American and European newspapers, journals, and in anthologies. In recent years, he began a career as an actor and has since worked on more than eighty projects, including theater, national television, and such award-winning films as Spotlight, The Second Life, and Brute Sanity. He is a graduate of Oberlin College and Harvard University.