Theater Review: “Hold These Truths” — Powerful Political Drama

By Helen Epstein

The play’s disparate elements have been blended into a riveting drama, energetically directed by Lisa Rothe, and nimbly performed by Joel de la Fuente.

Hold These Truths by Jeanne Sakata. Directed by Lisa Rothe. At Barrington Stage Company’s St. Germain Stage, Pittsfield, MA, through June 8.

Joel de la Fuente as Gordon Hirabayashi in the Barrington Stage Company production of ‘Hold These Truths.’ Photo: Scott Barrow.

Barrington Stage Company, the Berkshires theater that produces frothy mainstream musicals alongside serious, contemporary plays has chosen to launch its 25th season with a powerful, political, and timely one-person show that pulls no punches. Hold These Truths weighs the words of the Declaration of Independence – “We hold these truths to be self-evident” — against the words of a Quaker elder — “The ocean of darkness is a fact. The black squares on the great chessboard of the world are as unmistakable as the white squares. The real problem which always faces us is whether the white squares are on a black background, or the black squares on a white.”

Reflecting on this philosophical conflict as he walks toward the stage is Professor Gordon Hirabayashi, a 65-year-old retired professor of sociology who, as he tells the audience, has struggled to live by such principles, but has never been able to reconcile them with the memory of “the stigma. The shame. The nagging sleepless voice saying, No. It didn’t happen. I refuse to believe it.”

For 90 minutes Professor Hirabayashi (brilliantly performed by an extraordinarily agile Joel de la Fuente) commands a minimalist set — red floor, three chairs, a window pane, a light fixture that doubles as the moon — designed by Mikiko Suzuki MacAdams and artfully lit by Cat Tate Starmer. He removes his bifocals, slips off his cardigan, and goes back in time to become Gordie, the idealistic, eldest son of a Japanese farming family in the state of Washington, as well as some 30 other characters Japanese and Caucasian, male and female, old and young.

Mild-mannered and earnest in his white shirt and sweater vest, De La Fuente presents young Gordie as a typical all-American college student of the late 1930s. Except, of course, that as a Nisei, or second-generation Japanese immigrant, Gordie is coping with the demands of his family as well as the racism of pre-war society in the American Northwest.

“Deru kugi wa utareru ,” begins the Japanese proverb that Gordie’s Issei (Japanese-born) father repeats to him. “The nail that sticks out is the one that gets hit.” His father and mother, though Christian and rebels within Japanese society, nevertheless urge their son to conform, obey, be inconspicuous, avoid trouble.

Massive trouble arrives after the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor. In the spring of 1942, the U.S. government orders 120,000 Japanese Americans on the West Coast into internment camps on the grounds of military necessity. White Americans panic at the thought of a fifth-column in their midst. Japanese-American resistance to these mandatory deportations is minimal: very few “nails” stick out. But Gordie, a senior and student leader at the University of Washington, decides that he will.

Playwrights that take on as ambitious an agenda as Hold These Truths must grapple with many dramaturgical challenges, exacerbated by the one-person format. The expository task is somewhat easier if the protagonist is a well-known figure like Mark Twain or Martin Luther King, or if the play is about a recent public event, or if the performer is a well-known investigator/artist, such as Anna Deveare Smith.

Jeanne Sakata, a successful actor but first-time playwright, had the dual problems of introducing the audience to a relatively unknown hero as well as to a traumatic but largely forgotten military, social and political history. She was deeply interested in the facts, but had to fictionalize in the interests of drama. Her script sometimes feels overloaded with detail but, for the most part, it is powerful and very moving.

Just as Rosa Parks defied an order to relinquish her seat to a white passenger on an Alabama bus in 1955, Gordie Hirabayashi defied an 8 p.m. curfew ordered for all Japanese-Americans in 1942. His refusal to leave the University of Washington library and retire to his dorm for the night led to his arrest and conviction by the Seattle Federal District Court. His case was appealed, went to the Supreme Court, and was decided in favor of the government, 9-0.

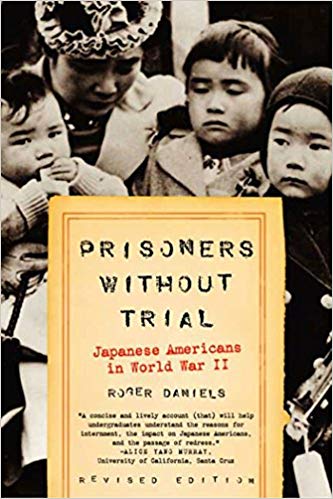

As Roger Daniels wrote in Prisoners Without Trial, “We now know that one Justice, Frank Murphy, wrote a dissent but, under pressure from his colleagues, modified it into a concurrence. In a strong statement which drew little notice at the time, Murphy insisted: “The broad provisions of the Bill of Rights… are not suspended by the mere existence of a state of war… It bears a melancholy resemblance to the treatment accorded to [Jews] in Germany.”

There are few concrete scenic elements in Lisa Rothe’s conception of the play – no props except for a battered suitcase and those three chairs; no indications of college or jail, none of the humiliating and vulgar signage of the kind displayed in last year’s International Center of Photography’s show of images from the Japanese Internment. But Hold These Truths draws extensively on legal documents, first-person accounts of the Japanese internment, personal interviews with and letters by the late Professor Hirabayashi, and several American history books – sources that lack poetic language, inherent drama, or cohesive narrative continuity. These disparate elements have, nonetheless, been blended into a riveting drama, energetically directed by Lisa Rothe, and nimbly performed by Joel de la Fuente (himself of Filipino, Chinese and Malaysian descent), who both narrates and enacts the action.

As young Gordie, he recounts that he did not fully register the extent of West Coast racism until he spent time in New York City, where he is struck by its absence. In one of several comic interludes, Gordie describes his surprise at being denied entrance to a venue — not because he’s Japanese, but because he doesn’t have enough money for a ticket.

When he returns to the West Cast after Pearl Harbor, it’s impossible for him to ignore the anti-Japanese violence.

“Smashed windows,” he recalls. “Death threats. Houses set on fire. Fucking Japs! Kill the Japs! The FBI knocking on doors. Arresting our fathers, handcuffing them. Young children clinging to mothers as agents ransack our homes. Mothers pleading and sobbing as our fathers are led to jail. And none of us Nisei can escape the shame burning in our faces….Our faces are the faces of the enemy.”

As Gordie faces the consequences of defying the curfew and the evacuation order, de la Fuente slips in and out of narrating the story and enacting it.

“Mom. Please. Listen to me…”

“No. You have a special duty. You’re the chonan, the eldest son.”

The family is being pressure by members of their community to make Gordie change his mind.

“You’ve got to make him understand, we have to obey the government, we have to prove our loyalty … They’re terrified you’ll make them suspect too. How can you be so selfish?”

Juxtaposed against a soundtrack of radio broadcasts and public announcements of the time, Gordie helps his parents empty their home and organize a fire sale in their front yard: “Icebox, stove, washing machine. Table, sofa, rocking chair. Mom’s Edison phonograph. Her black walnut piano.”

He recalls the advertisements hastily posted everywhere: Japanese evacuee must sell 1937 Pontiac coupe. Four very good tires, A-1 mechanical condition. Cash $250.00. Or, Japanese evacuee must sell 50-room brick hotel. Linens, furnishings, steam heat. Living quarters, garage.

Despite his parents’ entreaties, Gordie refuses to join them and his siblings in an internment camp. He chooses jail instead, first in Seattle and then, improbably, 1600 miles away in Arizona, where one of his cellmates is a Hopi. The endlessly versatile de La Fuente portrays this character as effortlessly as he does the sheriff, the various friends, judges, lawyers, and Gordie’s wife, who brings him their twin daughters on a visit to prison.

At the end of the play, de la Fuente pulls his cardigan out of the suitcase, puts his glasses back on, and updates his story:

“And the years pass, and I teach class, and my kids grow up, and my hair grays, and one night, after a poker game, I get a phone call out of the blue…”

Someone in D.C, has uncovered a secret report from the War Department, confirming that there was no “military necessity” for the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans. There is an investigation and his convictions are overturned.

Professor Hirabayashi reconsiders his father’s proverb: “The nail that sticks out is the one that gets hit.” Hold These Truths ends as quietly as it began, with the protagonist reflecting on the Declaration of Independence and Quaker philosophy. Our own reflections on American history, and how we would act under similar circumstances however, continue long after the curtain calls.

Helen Epstein is the author of ten books of non-fiction, including Joe Papp: An American Life and has been reviewing theater for The Arts Fuse since 2010.

Very fine review of one more tragic and criminal period of US history. The “actor of many rolls,” de la Fuentes, is to be commended as well. Just one unfortunate use of the term “white”– whatever that was (is). Americans were ethnicities and religions- Irish Catholic, Polish Jew, German Lutheran, etc. To underscore this, Koreans, Chinese, Pacific Islanders, etc were not interned during WWII. Some were uneasy about what happened to their fellow Asians, but just as many harbored resentment of Japanese for what the imperialists of Japan were doing to neighboring Asian people. It’s not really a simple case of “white” v “brown.”

Thnks for your comment. I agree. Many Americans did and still identify and are identified by ethnicities and religions. And yes, the Japanese are resented by many other Asian groups. Yet race was clearly a factor. Were any German-Americans interned during the second world war in the U.S.? There were before, during and after the second world war (and continue to be) many Nazi sympathizers in this country.