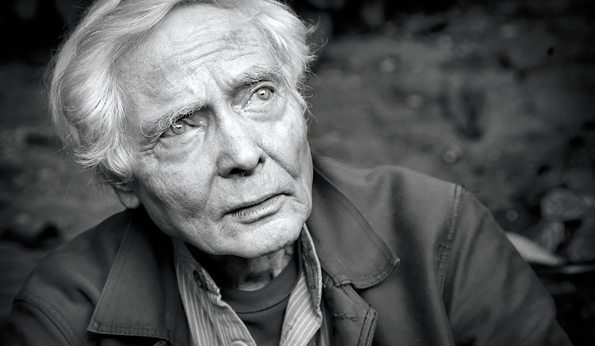

Arts Remembrance: Poet W. S. Merwin — An Appreciation

By Robert Israel

W.S. Merwin remained politically as well as artistically motivated all his life, often proclaiming the vital importance of activism.

The late W.S. Merwin.

Written 53 years before his death this past week, at the age 91 at his home in Peahi, Hawaii, American poet W.S. Merwin shared a revealing self-assessment:

It sounds unconvincing to say When I was young

Though I have long wondered what it would be like

To be me now

No older at all it seems from here

As far from myself as ever

— In the Winter of My Thirty-Eighth Year

Merwin’s observation is not wholly self-deprecating: he insists that readers see that pitiless self-awareness brings with it the responsibility to go beyond our appetite for arrogant self-importance. His prolific body of work dramatized this break from the self — he focused on ecological, mythological, and confessional themes. In the poem’s final lines, Merwin wrote:

Exhibiting talent as a writer early in his life, Merwin was, from the get-go, driven to use poetry to achieve a higher moral purpose — his version of tikkun olam, the Hebrew expression meaning to repair the world. He remained politically as well as artistically motivated all his life, often proclaiming that activism was far more important than all the awards his writing garnered, including serving as U.S. Poet Laureate and winning two Pulitzer Prizes (1971, 2009).

I first heard Merwin read his work as a student in Providence in the ’70s at an event where he announced he had donated his Pulitzer Prize winnings to Alan Blanchard, a painter who was blinded during an anti-Vietnam protest rally in Berkeley, California, in 1969. Like his fellow poet and former Princeton roommate, the late poet Galway Kinnell, Merwin was a dedicated pacifist. In that period he stood alongside the late Rev. William Sloan Coffin and the late poet/activist Philip Berrigan, S.J., and many others, participating in public events and demonstrations that denounced the Vietnam War.

I first heard Merwin read his work as a student in Providence in the ’70s at an event where he announced he had donated his Pulitzer Prize winnings to Alan Blanchard, a painter who was blinded during an anti-Vietnam protest rally in Berkeley, California, in 1969. Like his fellow poet and former Princeton roommate, the late poet Galway Kinnell, Merwin was a dedicated pacifist. In that period he stood alongside the late Rev. William Sloan Coffin and the late poet/activist Philip Berrigan, S.J., and many others, participating in public events and demonstrations that denounced the Vietnam War.

Born in New Jersey before the Great Depression and coming of age in the years preceding World War II, Merwin was initially influenced by American transcendentalists, particularly Emerson and Thoreau. Like the late Mary Oliver, Merwin turned to the natural world for solace and inspiration. He often quoted Thoreau’s line from his essay “Walking” — “in wildness is the preservation of the world” — to suggest how we, as humans, best live our lives by preserving (rather than exploiting) the planet as a sacred trust for for future generations. After Merwin’s passing, only a handful of American poets from his generation remain: the 88 year old Gary Snyder lives in the Pacific Northwest; Lawrence Ferlinghetti resides in San Francisco and turns 100 on March 24.

According to Lee Imada, editor of the Maui News, Merwin transformed his 18 acres of denuded land in Peahi, Maui into “a forest with 2,750 palms,” planting, pruning and nurturing the palms himself as part of a daily routine. Imada described Merwin’s home, which is surrounded by the verdant overgrowth, as a “post-and-pier and split-level built into the side of a hill with open beams.” That home and its acreage are protected from development in perpetuity by a “conservation easement with the Hawaiian Island Land Trust signed in 2014.” A foundation has also been established for writers to stay in Merwin’s home in the years to come.

Perhaps the best collection of Merwin’s work, which spans decades, is Migration: New & Selected Poems (Copper Canyon Press). In that 2005 collection “For the Anniversary of my Death” serves as a fitting epigraph:

Robert Israel writes about theater, travel, and the arts, and is a member of Independent Reviewers of New England (IRNE). He can be reached at risrael_97@yahoo.com.