Jazz Appreciation and Preview: James Carter — Life Begins at Fifty

By Steve Elman

Whom can we thank at the Boston Symphony Orchestra for choosing James Carter to be a featured artist at Symphony Hall? He’ll play Roberto Sierra’s Concerto for Saxophones and Orchestra, a showpiece for his mighty abilities, with the BSO on March 23 at 8 p.m.

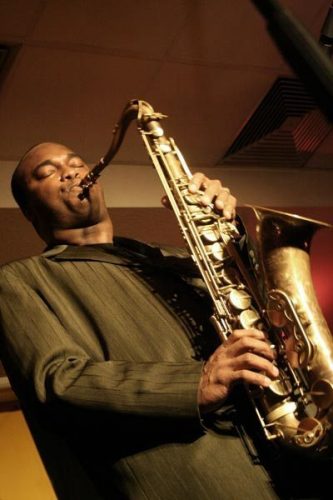

James Carter, a saxophonist of monstrous technique and gigantic sound. Photo: Chris Wurm.

I would venture a guess that the world divides into three groups – those who are enthusiastic fans of James Carter, those who have heard of him but haven’t yet heard him in person, and those who don’t know his work. That’s why having him perform in our town is such a gift from the BSO. Let’s hope it serves as an inspiration to local bookers to bring him into a club soon.

If you’re in Group Three above, let me try to explain why I’m in Group One.

When James Carter begins to play, whether he’s working in the smallest club or the most expansive concert hall, you can feel the room getting bigger. His monstrous technique and gigantic sound tap into the whole range of jazz saxophone, from Coleman (Hawkins) to (Ornette) Coleman. He can move from old-timey slap-tonguing to effortless circular breathing in a flash. He can coo and he can testify. He is at one moment a ballad player to rival Ben Webster, and at the next an uptempo racehorse as fast as John Coltrane playing sheets of sound.

James Carter in performance. Photo: Chris Wurm.

But there’s more to the man than honest respect for his forebears. I’ve never heard anyone as generous with his talent, so unselfish and unstinting that he seems like a one-man parade. He lets you feel as if he could lead you anywhere, and you find yourself compelled to go along with him.

So we are supremely lucky to be able to hear him as a soloist in Sierra’s “Concerto for Saxophones and Orchestra,” a work written expressly for him, a showpiece for his mighty abilities.

Carter’s presence isn’t the only thing noteworthy about this concert. The four composers on the bill are all people of color, and I cannot remember when I’ve been able to say that about a BSO program before. The program will mark the regular-season debut of conductor Thomas Wilkins, who directs the Omaha Symphony and customarily leads the BSO’s Youth and Family Concerts programs. It also will give Wilkins the chance to shine as an arranger-orchestrator. And the choice of works is beautifully balanced, bringing deserved attention to Puerto Rican composer Sierra, bowing to two African-American pioneers in classical music, Florence Price and Adolphus Hailstork, and closing with Duke Ellington’s “A Tone Parallel to Harlem.” The single downside is that there is only one performance.

My goal here is to celebrate Carter, but I can assure you that you’ll find plenty to like in the other works on the bill. Ellington’s “Harlem” is a classic, with a venerable history in symphonic programs going back to its 1950 commission by Arturo Toscanini (I expect that the BSO will be playing Luther Henderson’s orchestration). The Florence Price work (“Symphonic Reflections”) is an arrangement by Wilkins of themes from her third symphony, written in 1940, which, in so far as I know, has never been recorded in its entirety; this is a welcome honor for the first African-American woman to have her works performed by symphony orchestras, and a homecoming of sorts, because Price was an alumna of the New England Conservatory. And Adolphus Hailstork’s piece (“An American Port of Call”) is colorful and dramatic, firmly within the sphere of traditional classical music; another round of applause to the BSO for playing the work of a living African-American.

As for Sierra’s concerto, it’s a corker, and even though it will end the first half of the concert, I predict a standing O for everyone involved.

More about the concerto in a few paragraphs. But first, some words about Carter, jazz master.

He has always had jaw-dropping technical skills, playing the entire family of saxophones with equal facility. He received some of his first recognition and awards for his work on baritone, but he’s made some very big statements on tenor and soprano, and he has a bass saxophone that he plays beautifully when the occasion calls for it. Plus the alto, and the f-mezzo, and some bass clarinet, too. He’s probably got a vintage C-melody sax in his closet, ready to surprise us by covering something by Frank Teschemacher when we least expect it.

He has been a generous collaborator, recording with fellow saxophonists from every era of jazz – Buddy Tate, Flip Phillips, Johnny Griffin, Andrew White, Frank Lowe, Julius Hemphill, Hamiet Bluiett, and David Murray. . . not to mention his early partnership with pianist Craig Taborn and a very productive friendship with trumpeter Lester Bowie.

His own recordings are eclectic, but every one of them shows mastery. On his straight-ahead dates, he has offered original tunes that are snappy and well-constructed, along with a treasure trove of compositions that show a deep familiarity with a library-full of jazz recordings – like Bennie Moten’s “Moten Swing,” Matthew Gee’s “Oh Gee,” John Hardee’s “Lunatic,” Sweets Edison’s “Centerpiece,” Sun Ra’s “Hour of Parting,” Julius Hemphill’s “The Hard Blues,” and one of Anthony Braxton’s diagrammatically-titled pieces, “#400.”

Conductor Thomas Wilkins. Photo: BSO.

He has particular affection for two completely different jazz giants, tenor saxophonist Don Byas and guitarist Django Reinhardt. He has recorded Byas’s “Worried and Blue,” “Gloria,” and “Don’s Idea,” and owns a saxophone that Byas once played. Since 1999, he has regularly dipped into the Reinhardt songbook, ingeniously reinterpreting classics like “Nuages” and “Manoir de mes rêves,” and digging into more obscure items like “Heavy Artillery” and Mélodie au crepuscule.” (When I saw his organ trio last year, he said that his band was giving Reinhardt a “ghetto pass,” which is an excellent description of his distinctive approach to Django tunes.)

When he chooses a concept for a recording, the results are never garden-variety. For example, his tribute to Billie Holiday (Gardenias for Lady Day, 2003) includes only five tunes actually recorded by Holiday. The other repertoire was chosen to reflect aspects of Holiday’s personality, for example, Billy Strayhorn’s “A Flower is a Lovesome Thing,” and his own “Li’l Hat’s Odyssey.” And even the Holiday covers are distinctive. We’ve perhaps become inured to the starkness of “Strange Fruit,” but Carter’s arrangement restores the horror that was just under the surface in the original.

Or take Layin’ in the Cut (2000). On its face, this is a sort of fusion CD, rocking on the foundation of Ornette Coleman’s electric band, Jamaladeen Tacuma on electric bass and G. Calvin Weston on drums. But Carter is too savvy to go full-bore harmolodic or to fall back on funk clichés. The CD has a surprisingly lightness, and the two guitarists, Jef Lee Johnson and Marc Ribot, color the music rather than strongarm it with fuzz and distortion.

In January, Carter turned 50, stepping into that decade of life in which jazz artists unfortunately begin to be taken for granted. In his case especially, we must not make that mistake. As players hit their fifties, all that youthful fire and forties drive should be concentrated into a quest for higher artistic purpose. Carter is better equipped than most to make his own quest important and historic. In twenty years, will we be able to say that he is as influential, as significant, as the masters he reveres? I think we will, and I look forward to hearing him get there.

But in the meantime, I look forward to hearing him tackle Sierra’s Concerto for Saxophones. This is a classic concerto in form – three movements, fast-slow-fast, with no program other than an exciting dialog between virtuoso soloist and orchestra. Carter has center stage throughout the entire work, and he rarely has a moment to catch a breath. He is called upon to make transitions between tenor and soprano, sometimes with very little pause. Sierra asks him to hit some very high notes on soprano in the second movement, and to go even higher as it reaches its conclusion. There are arpeggios a-plenty, of course, but Carter is given the freedom to be soft and furry in the slow movement, just as he is bright and brassy in the first and last.

The musical language of the piece is approachable, grounding the more abstract harmonies in Latin rhythms in the first movement, and providing some harmonic familiarity by drifting into augmented blues in the third. The mellow heart of the concerto is its second movement, written mostly tonally, with an appealing theme that recalls the ancient standard, “When I Grow Too Old to Dream.” Is there room for improvisation? It sounds to me as though the cadenzas are at least partially improvised, and Sierra gives Carter a crucial developmental role in the last movement by asking him to make the transition from polytonality to basic blues.

By cruel circumstance, at exactly the same time that Carter is playing with the BSO, Fred Hersch is reviving his song cycle “Leaves of Grass” at the Berklee Performance Center. . . oh, for a time machine. But I have to choose, and I choose Symphony Hall. If you join me, by the time Roberto Sierra’s concerto is over, I think you’ll be standing too.

More:

James Carter’s discography is rich. It is unusual in that he has made a point of putting himself alongside living jazz giants – many of whom have passed away since recording with him. To give a sense of his many homages, I have noted the death years of some of his collaborators in the recordings below.

His only classical release so far spotlights the work he is playing with the BSO on March 23:

Caribbean Rhapsody (Rec 12/21/2009, Warsaw, Poland; 3/18 & 19/2010, New York City; released on Emarcy, 2011) – Carter, ts/ss; w. Sinfonia Varsovia Orchestra, conducted by Giancarlo Guerrero, on Roberto Sierra: “Concerto for Saxophones and Orchestra”(2002); w. Regina Carter, violin and Akua Dixon String Quintet on Roberto Sierra: “Caribbean Rhapsody”; and performing a capella on two solo “Interludes”

He has engaged in many multi-reed projects, some collective and some under the leadership of other musicians:

Tough Young Tenors (1991), with Walter Blanding, Tim Warfield, Herb Harris, and Todd Williams

Julius Hemphill (died April 1995) Sextet: Fat Man and The Hard Blues (1991), and Five Chord Stud (1994), w, Marty Ehrlich (music dir), Sam Furnace, Andrew White, Aaron Stewart, Alex Harding, Andy Laster.

SaxEmble: Inappropriate Choices (1991) w. Frank Lowe (died September 2003), Michael Marcus, Carlos Ward, Phillip Wilson (died March 1992)

SaxEmble (1996) w. Frank Lowe, Michael Marcus, Cassius Richmond, Alex Harding, Bobby LaVell and drummer Cindy Blackman

Wendell Harrison’s Mama’s Licking Stick Clarinet Ensemble – Rush & Hustle (1994)

Swing is the Thing (2000), with Flip Phillips (died August 2001), Joe Lovano

World Saxophone Quartet (replacing Julius Hemphill) – Yes We Can (2011), with Hamiet Bluiett (died October 2018), David Murray, and Kidd Jordan

Carter recorded with trumpeter Lester Bowie on one of his own CDs (see below) and with Bowie’s New York Organ Ensemble (1991) and the Phillip Wilson Project (2008).

This is a selected discography of Carter’s releases under his own name, by recording date:

On the Set (Columbia, 1993), with Craig Taborn, Jaribu Shahid, Tani Tabaal

Jurassic Classics (1995), with Craig Taborn, Jaribu Shahid, Tani Tabaal

The Real Quietstorm (1995), with Craig Taborn, Jaribu Shahid, Tani Tabaal, Dave Holland, Leon Parker

Conversin’ with the Elders (Atlantic, 1996), w. Craig Taborn, Jaribu Shahid, Tani Tabaal, and guest artists Hamiet Bluiett, Buddy Tate (died Feb 2001), Lester Bowie (died November 1999), Sweets Edison (died July 1999)

In Carterian Fashion (Atlantic, 1998), with Cassius Richmond, Dwight Adams, Kevin Carter, Cyrus Chestnut, Craig Taborn, et al.

Chasin’ the Gypsy (Rec. c. 1999; released on Atlantic, 2000) – Carter, ts/ss/bass saxophone/f mezzo saxophone; Regina Carter, v; Charlie Giordano, acc; Jay Berliner and Romero Lubambo, g; Steve Kirby, b; Joey Baron, dm; Cyro Baptista, per (includes six compositions written by or associated with Django Reinhardt)

Layin’ in the Cut (2000), w. Jef Lee Johnson and Marc Ribot, g; Jamaladeen Tacuma, e-b; G. Calvin Weston, dm

Gardenias for Lady Day (2003), w. vocalist Miche Braden, and strings on some tracks arranged by Carter himself

Live at Baker’s Keyboard Lounge (2004), with David Murray, Franz Jackson (died May 2008), Johnny Griffin (died July 2008)

James Carter Organ Trio: Out of Nowhere Live at the Blue Note (2004), with Gerard Gibbs, organ and Leonard King, Jr., drums, and guest artists Hamiet Bluiett & James “Blood” Ulmer

Present Tense (2008), w. Dwight Adams, D. D. Jackson, Rodney Jones, James Genus, Victor Lewis, Eli Fountain

The James Carter Organ Trio at the Crossroads (Rec. February 2011, New York City; released on Emarcy, 2011) – with Gerard Gibbs, organ and Leonard King, Jr., drums

He also explored Django Reinhardt repertoire in this anthology:

The Django Reinhardt Festival Live at Birdland: Gypsy Swing! (Rec. 2002, Birdland, New York City; released on Kind of Blue, 2006) – includes three tracks with Carter, ts; Dorado Schmitt, v; Ludovic Beier, acc; Angelo Debarre, Serge Camps, & Samson Schmitt, g; Jay Leonhardt, b; Grady Tate, dm

Steve Elman’s four decades (and counting) in New England public radio have included ten years as a jazz host in the 1970s, five years as a classical host in the 1980s, a short stint as senior producer of an arts magazine, thirteen years as assistant general manager of WBUR, and currently, on-call status as fill-in classical host on 99.5 WCRB since 2011. He was jazz and popular music editor of The Schwann Record and Tape Guides from 1973 to 1978 and wrote free-lance music and travel pieces for The Boston Globe and The Boston Phoenix from 1988 through 1991.

Tagged: Boston Symphony Orchestra, James Carter

As a jazz and other avant music producer in Cambridge (yes, I said it, Jazz is avant :-), I couldn’t afford James Carter’s band of any size I’m sure, (solo?) but he’s welcome to consider my admiration and wish. Need a bigger venue than the Lilypad too! But then, how do you convince Jazz Clubs to book him when l venture to guess they never heard of him and if so, don’t appreciate him enough to book him? Thanks for the exposure of his name, Steve. Now, if those club owners got comps or were interested enough that they’d attend and be a impressed, then I’d say the fusion of Classical and Jazz has been a “market” success, but I’m not counting on it. I’ve known of Carter’s playing since the early ’90s — I hope it won’t take a whole generation to really hear him live!

This guy is a pure Vegas act, and with his energies and strengths he just might be able to work out a one-man “jive show” in the vein that would attract spectators in the casinos. As someone who fell in love with jazz as played deep on Chcago’s Southside by Sonny Stitt, Gene Ammons, then closer to the loop later on with Dexter, Wardell, Jaws, Griffin and dozens of other, I can’t tolerate jive players and showmen anymore. But it’s hard making a living as an. instrumentalist, so I wish Carter well. But I hope some of the public are aware that he is he poorest representative of this grea t=American music.

For starters, check out the Great American Songbook and its Composers. Those are the standards that served all of the major jazz soloists so well.