Arts Commentary: My Blackface Confession

By Gerald Peary

Did I try to fit in at my segregated school, betraying my father and his values to be a popular white boy?

Like the governor and attorney general of Virginia, I have a shameful blackface story to reveal from my growing up in the South, something I’ve felt guilty about forever.

It’s what I did one day at age 11 in South Carolina’s capital city of Columbia. I was a white boy in 7th grade at Hand Junior High, a segregated school in the year 1955.

This dreadful memory had been closeted forever, until I was “outed” at the 50th reunion of the 1960 graduating class of Columbia’s Dreher High School. I ventured there from my “People’s Republic of Cambridge” bubble (I moved north for college, and stayed north) into a sea of white-haired Republicans, most of whom still lived in Columbia. But one more liberal classmate, who now owns a farm in the Midwest, came up to me and said, “Do you remember wearing blackface in junior high?”

Gulp. Do I ever.

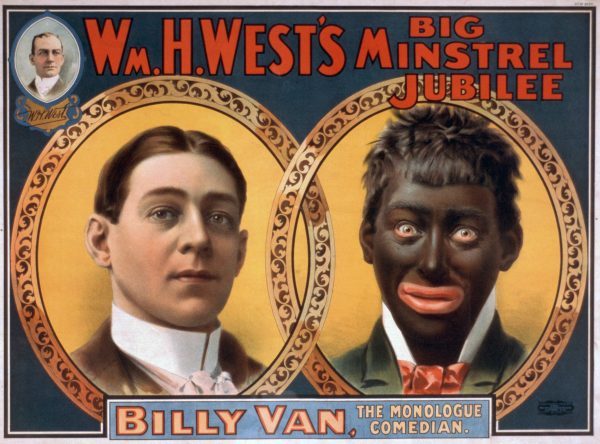

I confessed to my wife what I’d done only fifteen years into our relationship. Amy was properly shocked as I recalled for her the day that I appeared on stage in a school talent show with burnt cork on my face. It was a two-hander, an old-time minstrel routine performed by me and a classmate named Ray, he half-a-foot taller and also in blackface. We strolled on stage in suspenders and baggy pants portraying, I guess, hideous stereotypes of ostensibly lazy, ignorant black folks; and we spoke in an exaggerated white man’s version of “Negro” dialect, like Joel Chandler Harris doing Uncle Remus.

I can quote our exact words. They’ve stuck in my head, the three unconscionable lines of dialogue, the third a ha-ha punch line:

Ray (stretching): “I sho’ am tired!”

Me (stretching): “I tired too!”

Ray: “Yeah, you is tired, but I twice as tired as you, ‘cause I twice as big as you.”

With that, we shuffled off stage, to laughter and applause from the appreciative white junior high audience: students, teachers, administrators.

I surely knew better than to participate. My parents were immigrant Jews from Europe, and, my father especially lectured me against holding any racial prejudices. In Columbia, he headed the biology department at two black colleges; Benedict College and Allen University. At our home there, we dared break the color line, as African-American colleagues of my father were invited over for dinner.

So why didn’t I resist putting on blackface? I and my brother were just kids, and under a lot of psychological pressure because of where our father taught. Anytime we told a white adult, parents of our friends, they would recoil in disgust. Some children were not allowed to play with us. A house we wished to buy fell through when the owner found out my father was at a black university.

Did I try to fit in at my segregated school, betraying my father and his values to be a popular white boy? This I don’t remember at all. I assume my South Carolina teachers set this talent show up, found the racist minstrel show routine, cast me and directed me, a vulnerable 11-year old. But analogous to some survivors of sexual abuse, I can’t help feeling complicit in this ignominious, scarring moment of my life. I’m truly, truly sorry.

Gerald Peary is a Professor Emeritus at Suffolk University, Boston, curator of the Boston University Cinematheque, and the general editor of the “Conversations with Filmmakers” series from the University Press of Mississippi. A critic for the late Boston Phoenix, he is the author of nine books on cinema, writer-director of the documentaries For the Love of Movies: the Story of American Film Criticism and Archie’s Betty, and a featured actor in the 2013 independent narrative Computer Chess. He is currently at work co-directing with Amy Geller a feature documentary, The Rabbi Goes West.

When I was in the 2nd grade my mostly white elementary school put on a play version of Little Black Sambo.

I was a determined little 7-year thespian and got cast in the lead. Sambo, as the story goes, is forced to give up his new clothes to each of four hungry tigers in order to not get eaten. The conceited tigers argue over who is best dressed and began chasing each other around and around until they turn to butter. Sambo gets his clothes back and, with the butter, makes pancakes with his mother, Black Mumbo.

The play was done silent for some reason. No offensive dialect necessary. I couldn’t remember the order of the clothes I was supposed to shed. I didn’t want to be on stage in my underwear anyway, so I was moved to play the father, Black Jumbo.

Fortunately, my reputation remains sort of untainted because we were not put in blackface. I’m not sure why we did this as a play, if the audience understood the story, or if any of this made sense even at the time. Butter? A white kid is called Black Jumbo?

I see your point, I wanted to belong too. Until I came to Europe, and saw that you don’t have to be an idiot macho man, that you can live for your country. So yes, I see the urge to belong, to be part of the tight boys.

My dad used to perform in the “Minstrel Show” that the Rotary club put on every year in the small Ontario town where I grew up. Same sort of dialogue & a lot of Jolson hand waving. I don’t know what my parents thought about it. They both grew up in Saskatchewan, so they had no experience of the sort you had. Amazing how deeply embedded & how much on the surface. I was just writing about Shipman & Griffith & their casual references to “Chinkie” & “Yellow Man” – common parlance at the time.

Great strength & humility in this confession, Gerry.

I think writing this took a lot of guts, Gerry. I applaud your honesty. I do think you needn’t be that upset- you were 11, for god’s sakes, and it was an environment that was pushing you in a certain direction. With a lot of this blackface controversy, it’s about the environment that people were in, that signed off on these kinds of images and encouraged or endorsed this stuff and made people feel like it was ok.

It sounds like your family was doing tons of good work that vastly outweighed this offence- teaching however many African-Americans in schools and helping them further their educations means a lot more than the situation that you’re talking about, I think.

I wonder if the next stage of MeToo and these racial-based controversies will be about people having to come clean about things they’ve said and done in the past, admitting to past behavior that they are ashamed of and by doing so showing how prevalent racism/sexism have been and how the complains from women and people of color aren’t just victimization, whining, or PC bullshit.

Matt

I completely understand Gerald’s shame.

We’re not talking about excuses we’re talking about emotions.

When I was six I was at a Tony private school in Cambridge Buckingham School and there was one African-American child in the entire School.

One lunch in 1960 he was giving me a hard time about I don’t know what and I turned to him and I said “at least I’m not black”

I have few regrets in my life but that one tops the list.

60 years later I think about it all the time.

Shame does not go away.

Paul

It definitely doesn’t. I have said plenty of things I really regret in retrospect. I think we all have black marks on our records, prejudices we never addressed, assumptions that aren’t justified and created out of fear, ignorance, insecurity, or whatever else.

The important thing is to at least have the decency to regret them, think about what happened, and try to do better in the future. I have no patience for those who refuse to do this anxiety-inducing but necessary work.