Music Interview: Michael Daves on How Anyone can be a Bluegrass Singer

By Noah Schaffer

“You don’t really know how to perform bluegrass until you interact with others.”

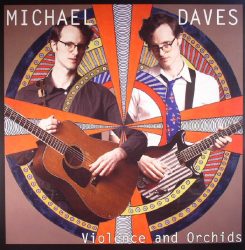

In a bluegrass world that’s filled with hot pickers, Michael Daves made his name as a singer. Now Daves has turned himself into a fine performer on mandolin and guitar, but his powerful, soulful vocals are still what make him instantly identifiable. Now in his early 40s, Daves first came to the attention of many listeners through his duets with Chris Thile. In 2017, he released Orchids and Violence, an ambitious LP in which the same songs recorded twice, once in a traditional bluegrass style and then again in an experimental electric style.

On Friday, Daves will be performing at opening night of the Joe Val Bluegrass Festival in a combo that also features two of the music’s revered veterans, Tony Trischka and Kenny Kosek. He spoke to the Arts Fuse from his New York home.

Arts Fuse: You’ll be part of an all-star New York bluegrass multi-generational group — will you be playing as a trio? What are Tony Trischka and Kenny Kosek like to play with?

Michael Daves: We’ll have a bass player, Larry Cook. Tony and Kenny are both very engaged and engaging players, almost childlike in their enthusiasm for finding new sounds and for musical interactions. Both of them are great improvisers and perpetually fascinated by what everyone around them is doing, so it’s really a delight. Also, the first bluegrass band I was in, in Atlanta, was with Jim Tolles, who was a member of Breakfast Special, along with Tony and Kenny. The dobro player Stacy Phillips, who passed away recently, was also in that group. He’s going to be honored at Joe Val; our set in particular will include some Breakfast Special music.

AF: Speaking of the New York bluegrass scene, was it something that drew you to the city, or did you simply find yourself living in New York playing bluegrass?

Daves: I ended up in New York after I’d been living in Western Mass. I attended Hampshire College and lived in the Pioneer Valley for eight years. My wife, who is a visual artist, and myself wanted to move somewhere where there were more professional opportunities. I had New York connections so we came down for those reasons, and it just happened to coincide with me getting back into bluegrass, which I grew up with. My parents play it and I’d played it growing up but had gone more into jazz and experimental music. So I returned to my personal roots with a fresh perspective, and it just so happened that this was in 2003 and the New York bluegrass scene was really starting to take off at that time, and I got swept up in it. I have done my best to grow and nurture the genre through teaching. I think it’s really one of the best scenes in the country as far as jamming goes. I’m always trying to talk my musician friends into moving here — I was convincing quite a few, but recently we’ve lost a lot of players to Nashville, because it’s a place where they can buy a house. And, of course, Boston has a very strong scene too.

Guitarist Michael Daves Photo: Nonesuch.

AF: What makes an urban bluegrass scene like Boston or New York different from Nashville?

Daves: I ask my friends in Nashville and they tell me they are surrounded by amazing and legendary professional musicians, but people don’t get together and jam in Nashville the way that they do in NY and Boston. It has a lot to do with a city’s environment, the way it contributes to musical community. Traditional music functions as a survival tactic for city life because you end up getting together and seeing a musical family — it makes the big city feel small and cozy. One of the great things about music scenes like that is that you get musicians at all levels. I’ve hosted a monthly jam here in New York every first Monday [at the Rockwood Music Hall] since 2005. Last week Tony Trischka showed up and we had students and complete novices and everyone else jamming together, it’s beautiful.

AF: Speaking of jamming, Joe Val and the Boston Bluegrass Union are devoted to offering all kinds of organized and informal jamming opportunities. How important is it to play bluegrass with other people?

Daves: For bluegrass in particular it’s vital if you want to learn the music. There are a lot of great online resources and books and videos where you can sit in your room and learn music on your own. But you don’t really know how to perform until you interact with others. This is a folk tradition and its essence needs to be passed along in person and at a festival environment. There you have a combination of jamming, workshops, and also seeing performances — it’s so important to have that absorptive experience to really get it. You can only get so far on paper.

AF: Are you doing a workshop at Joe Val?

Daves: I’m teaching a guitar workshop on Saturday morning. My guitar workshops include a lot of vocal work, like how to translate a sung melody to the instrument, maintaining ornamentation and phrasing. I have an online school on ArtistWorks and I try to explore that connection there as well. A lot of bluegrass guitar music is heavy in terms of notes and licks. I’m committed to getting people to be able to hum something and play it. The richness of the music is shaped by the vocal — it’s not the chord progressions, which are usually third chords! Compare it to Stravinsky’s music and it’s pretty simple. But vocal ornamentation makes things complex and rich — and that’s often overlooked.

AF: That leads us to your vocals, which I wanted to talk about. Your Georgia roots certainly come through in your singing. Have you refined and developed your vocal approach over the years or does it just reflect how you grew up singing?

Daves: My approach is about getting deeper and deeper into the style of my influences, responding to the singers that I listened to, like Bill Monroe and Jimmy Martin and Ralph Stanley. And responding to their visceral interest in singing — how they bring a physicality that ups the emotional content. My singing is stylized for sure — it’s not how I talk. I do try, as much as possible, to work with the natural resonances of my voice. That’s what I want my students to learn: How does their voice resonate, how do they engage in that creatively? It’s a process.

AF: So bluegrass singing is something that can be learned regardless of where the singer is from? []

Daves: It absolutely can be learned. And that’s a common misconception, especially with folk styles, that people think it’s something you’re either born with it or you can’t do it, and that’s just not true. Although I grew up in Georgia and got to spend a good amount of time with some old-school bluegrass singers growing, now I’m based in New York and teaching a lot of people who didn’t grow up in the South. Once thing I encourage people is not sing in an accent, not be going in costume. I tell them to study those classic performances — the Stanleys, Bill Monroe — and pay attention to the melodic detail, the way the notes move, pick up on the rhythm and the ornamentation and dynamics and really get very deep into the classic style, and still sound like you. Now it may take longer to develop some of the basics of pitch and you have to be willing to open the voice tonally … but anyone can bring their experiences and emotions to their singing.

AF: You mentioned that while you were performing bluegrass and also playing experimental music. Would you suggest bluegrass players try other styles?

Daves: That period came because at Hampshire College I had great the fortune of studying with multi-instrumentalist Yusef Lateef. His music was very progressive, very forward thinking and even in his 90s he was still writing very new music. There were two main takeaways from him: One was the importance of learning to sound like yourself, to bring your own emotions and experience to the music and convey them through sound. The other thing was to continue to try to find new sounds, not to settle for doing what you’ve always done. Yusef knew I was into bluegrass and that it was part of me. I’d sometimes bring a mandolin to class and play his sort of out-there music — not well. He encouraged me to write a bluegrass concerto, which I haven’t gotten to yet.

The fact that Orchids and Violence had two parts was in the spirit of Yusef and his idea of expressing who you are as well as finding new sounds. And it was also in the spirit of bluegrass and folk music; these are very old songs on the album, and it’s fascinating how a song can be passed down and sung by generations of people who all bring their own thing to it. That project was a testament to the enduring value of those songs, that they can be taken out of their customary context and still work. I’m inspired by tradition but that doesn’t mean serving it in an expected way. Yes, it means appreciating that these songs have had a long life before you got to them, and embracing how the music came to be. But it is also about moving the ball forward, which is what the innovators of bluegrass did back in the day. Back in the day, Bill Monroe was controversial, an iconoclast. The music became codified, but we wouldn’t have it if he hadn’t taken chances in the first place.

AF: What are you working on next?

Daves: I’ve got two projects in the works. One is a bluegrass record that I recently started with Tony Trischka and Brittany Haas and Mike Bub and Jenni Lyn Gardner. I am also working on writing a bunch of new music for an electric band called Wax Lion, which is a trio that grew out of needing to perform the music from the electric side of Orchids and Violence. We’re developing new music that reworks old American spiritual hymns and religious ballads from the 1700s and 1800s — but in a loud and experimental direction.

Over the past 15 years Noah Schaffer has written about otherwise unheralded musicians from the worlds of gospel, jazz, blues, Latin, African, reggae, Middle Eastern music, klezmer, polka and far beyond. He has won over ten awards from the New England Newspaper and Press Association.