WATCH CLOSELY: Ted Bundy, Archetypal Sociopath

By Peg Aloi

What is admirable about Conversations with a Killer is that it is as compelling an exploration of the monster’s victims as it is of Ted Bundy.

Judging from the chatter on social media these days, people can’t seem to get enough of sociopathic serial killers. Recently, the television series You found an enthusiastic audience on Netflix after a somewhat less eventful premier on the Lifetime network. The show attracted some positive reviews, although most critics said it was fairly silly on many levels, but somehow it managed to be rather addictively entertaining. And reader, I concur. What was more interesting was the number of fans the show attracted, the shocking number of women who began to fawn over star Penn Badgley, and who proclaimed their love and adoration for his character, Joe Goldberg, a bona fide serial killer. In the wake of this somewhat alarming Twitter trend, Netflix replied that there are “many hot men” on its streaming service who are NOT murderers. Not long after that Badgley found it necessay to remind fangirls that his character was a cold-blooded killer. A considerable number of female viewers admitted the actor was attractive but that his character scared them. Somehow it is stimulating when the line between flesh and fantasy becomes fuzzy. I mean, he’s so cute and he loves me and the sex is great (except for that time it wasn’t)! But what if he decapitates me in my sleep? But if he decides not to, he’ll make strawberry waffles for breakfast. OMG he’s so sweet.

True crime podcasts (like Serial) and shows (like The Keepers or Wild, Wild Country on Netflix) have been proliferating in recent years, and continue to be extremely popular. Even fact-fiction hybrids like Errol Morris’ uncategorizable series Wormwood generate curious audiences. Controversy aside, the popularity of You demonstrates that even a growing awareness of sociopathic behavior or toxic narcissism (partly due to our POTUS being tagged as such by psychology professionals) doesn’t guarantee that potential victims can recognize their own vulnerability to abuse (or propaganda).

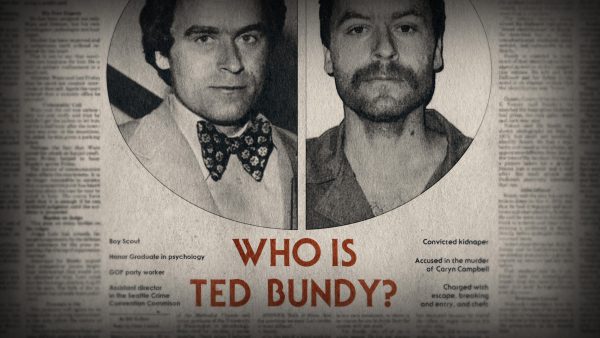

But Joe, a handsome, erudite bookstore manager, is fictional. Ted Bundy, a handsome law school student and former suicide crisis hotline volunteer, was horrifyingly real. Bundy, suspected of killing at least thirty six women in several states between 1974 and 1978, was executed by electric chair in January of 1989. He has become one of the most notorious serial killers of all time, perhaps because he was the first criminal to have portions of his trial broadcast live on national television. Bundy managed to escape police custody twice after being arrested for murder: at one point he jumped out a courthouse window and escaped into the woods for several weeks before hunger drove him to turn himself in. On top of that, his insistence on acting as his own lawyer during his trial made him a fascinating icon for true crime buffs.

Two new media properties take on the notorious serial killer in 2019: one a documentary series on Netflix, the other a feature film starring Zac Efron as Bundy. And both are in the hands of the same director: filmmaker Joe Berlinger, well known for his award-winning documentary collaborations with Bruce Sinofsky (the Paradise Lost trilogy, My Brother’s Keeper, and Metallica: Some Kind of Monster, among others) and later his work on the Sundance Channel series Iconoclasts. The Netflix series, Conversations with a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes, is a six part program that is so suspenseful — and also so chock full of information — that it would be a fool’s errand to absorb it all in one night. But, dear reader, that is precisely what I did. (Not sure I recommend this, and if it is late at night you might want to double-check the locks on your doors and windows.)

The “tapes” mainly refer to a series of conversations recorded while Bundy was in prison in the early ’80s with journalists Stephen Michaud and Hugh Aynesworth. The two men are interviewed about those years, recalling how long it took to get Bundy to admit his crimes. He finally felt comfortable when he decided to speak about himself in the third person — as a psychological case study. Some of the details are disturbing in the extreme; some of Bundy’s victims were raped, brutally assaulted, even decapitated. Some of their remains were never found. It is worth noting that, in the ’70s, forensic science was much cruder than it is now and DNA testing was non existent; given these limitations, identification of the remains was difficult if not impossible. Thus Bundy’s willingness to divulge details of the killings was, horrifically enough, crucial in bringing closure to victims’ families.

At that time national news broadcasts did not always cover local crimes, so it took years for law enforcement to make connections between the murders of young women in Oregon, Washington, Utah, Colorado and California. Bundy’s victims share an eerie resemblance: most were white, slender, long-haired, between the ages of 18 and 25, and were students, nurses, teachers or other middle class professions. Their disappearances were met with bewilderment; none of them were known to be “wild” or “party girls.” The assumption in those days was that a girl who got herself raped and murdered must have been asking for it. The series shows bracing archival footage of young women organizing demonstrations to voice their fear of Bundy and to protest the failure of law enforcement — as well as to condemn the assumption that women themselves were somehow responsible for dressing or behaving in a way that made them complicit. One of Bundy’s ploys was to wear a fake cast on his arm. He would hang around a campus or parking lot and ask a young woman to help him; he would then pull her into a secluded place or into his car. This same technique was fictionalized in the German-Dutch thriller The Vanishing.

The series’ production design is slick but straightforward, so it is relatively simple to stay on top of the many time jumps and chronological findings, the connections among various events, locations and people. Much was made at the time of Bundy’s charisma and air of normalcy: family, friends, and neighbors were utterly shocked to hear of his monstrous crimes. What is admirable about Conversations with a Killer is that it is as compelling an exploration of the monster’s victims as it is of Bundy. And it makes a larger cultural point: it is a portrait of what America became in the wake of Bundy’s reign of terror: fearful, suspicious, cynical, and obsessed with serial killers.

Peg Aloi is a former film critic for The Boston Phoenix. She taught film and TV studies for ten years at Emerson College. Her reviews also appear regularly online for The Orlando Weekly, Crooked Marquee, and Diabolique. Her long-running media blog “The Witching Hour” can be found at at themediawitch.com.

Tagged: Conversations with a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes, Netflix, Peg Aloi

*4 part series