Book Review: “The Burning House” — Diversity in Segregation

By Jeremy Ray Jewell

Anders Walker’s The Burning House sheds fascinating light on a forgotten piece of intellectual history in the Jim Crow South.

The Burning House: Jim Crow and the Making of Modern America by Anders Walker. Yale University Press, 304 pages, $30.

Gunnar Myrdal, a Swedish economist, sociologist, and Social Democratic politician, wrote American Dilemma in 1944. In it, he argued that any effort to eliminate racial disparities in America would necessitate wholesale assimilation of black Americans into white culture. This assumption eventually ran through most of the social sciences of the day, with its suggestion that African Americans possessed no distinctive culture. The implication was that, because of racism, what culture blacks had could be classified (or dismissed) as “pathological.” Chief Justice Earl Warren cited Mydral’s study in his opinion in Brown v. Board of Education; the Court mentioned it in a footnote to the ruling. The belief that the decision was based on antipathy toward black autonomy stirred a chorus of opposition from ardent segregationists, white Southern moderates, and blacks alike. Nevertheless, the legacy of Myrdal’s views persisted throughout the dismantling of Jim Crow. Martin Luther King Jr., who has come to personify the period in popular historical memory, even cited Myrdal in his memoir of the Montgomery bus boycott.

“Do I really want to be integrated into a burning house?” asked James Baldwin in The Fire Next Time. Baldwin may have been thinking of the conflagration in William Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom!, where a home is set ablaze by the white planter’s slave daughter. Anders Walker’s The Burning House borrows its title from both of these bonfires as it sheds important light on a forgotten piece of intellectual history in the Jim Crow South. Walker labels his subject “southern pluralism.” Several events galvanized proponents of “southern pluralism” to speak out, from the murder of Emmet Till to Rosa Parks. None, however, were more significant than the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education ruling. The well known names whose dialogue animates The Burning House — both directly and indirectly — are commonly associated with either black literature, Southern literature, or both: Zora Neale Hurston, Eudora Welty, Flannery O’Connor, Ralph Ellison, Richard Wright, William Faulkner, Robert Penn Warren, and James Baldwin. What all these voices share in common is a concern for the preservation of the admirable traits of traditional Southern culture, particularly those which stood against the growing power of modern industrial capitalism. Ultimately, writes Walker, a white Virginian on the Supreme Court, Justice Lewis F. Powell Jr., would bring this notion of ‘southern pluralism’ into the heart of the nation’s debates on diversity.

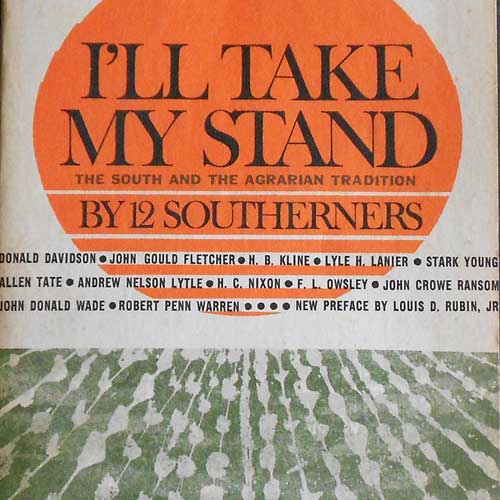

Of course, Southern critiques of industrial capitalism are much older than the region’s modernist literature. Antebellum proponents of slavery had long put forward arguments that insisted Northern and European industrial workers were worse off than the South’s slave laborers. But the criticism that came from the Jim Crow South was distinctively cultural in its concerns. In many ways, the conflict was introduced by the 1925 Scopes trial, which generated, from H.L. Mencken and others, broad criticism of Southern culture as unusually backward. The Southern Agrarians, twelve writers who coalesced around a group of Vanderbilt University writers known as the Fugitives, published their agrarian manifesto I’ll Take My Stand in 1930. The young Robert Penn Warren’s contribution to the volume (and also his first published essay) was “The Briar Patch.” The title alluded to the black folktale of Brer Rabbit and the briar patch, which was seen as an analogy for segregation: that, though seemingly inhospitable and hostile from the point of view of outsiders, the briar patch of segregation afforded blacks in the South considerable freedom in terms of autonomy and self-definition. The essay was not unanimously approved of by the other Agrarians. For its time, it was remarkably sympathetic to black culture.

Although an older Warren would not stand by all of “The Briar Patch,” he did maintain a belief in its central points. In the wake of Brown v. Board of Education and the spread of Mydral’s ideas, Warren focused on asserting the value of the segregated culture of the Southern “lower classes,” white and black. As Walker tells us, Warren had long fostered a preference for the ‘lower classes,’ heightened by his disdain for the British class system during his time at Oxford. This interest in what we may call ‘rootedness’ also plays a big part in Warren’s analysis of the Civil Rights Movement in Who Speaks For The Negro? For Warren, integration from the top down was bad for all parties, not only because of the popular violence which may result from it, but its pervasive elitism. In “The Briar Patch,” Warren argues for the need for working-class blacks to maintain their culture (or at least to maintain a creative class) and stay in the South. For white Southern moderates, such as Warren, a commitment to the lives of common folks led them to be skeptical of Brown v. Board of Education — both in terms of opposing the homogenizing effects of assimilation and the top-down imposition of desegregation.

Warren found a surprising ally in his commitment to grassroots culture: Ralph Ellison. He agreed with Warren that black culture was not pathological and did not need to be assimilated into “mainstream” culture. For Warren, this presumably held true for white Southern cultures as well. For Ellison, white culture was more likely to include pathological traits. In Invisible Man, he echoes Zora Neale Hurston’s suggestion of black “racial genius”; the novel’s lonely subterranean black protagonist observes America from below. What united Ellison and Warren was a belief in the value of heterogeneity and the traditions of the lower rung in the face of both rampant industrialization and consumerism — as well as the threat of homogeneity. You see this in both Ellison’s Invisible Man (the author’s disenchantment with Communism) and in Warren’s All the King’s Men, which was probably inspired by the career of populist Huey Long of Louisiana.

What both writers shared, in Walker’s assessment, was a “concern that ‘right-thinking’ liberals might threaten diversity,” a concern that sat on a “contrast between the impersonal, idealistic, right-thinking North and the intimate, […] wrong-thinking South.” Richard Wright took a contrary position; he agreed with Myrdal. Wright, along with Ellison, thinks that blacks possessed a critical role in world history, but he was much more distrustful of traditional black culture. He famously attacked Hurston’s depictions of lower-class rural blacks in the South as a form of minstrelsy. Ironically, Wright made important class distinctions about black culture in his writings, yet Walker suspects that he was unable to empathize with Hurston’s autonomous black community of Eatonville, Florida because of his own background. The clash between Wright and Ellison on folk culture can be most clearly seen in their thoughts on Spain; Wright described the country as primitive, backwards, and superstitious; Ellison thought it provided a useful example of how a people’s traditional art may be repurposed.

William Faulkner fell on the anti-Myrdal side of the spectrum. After reading Richard Wright’s memoir Black Boy, he suggested that that he work more in fiction. For Faulkner, the creation and propagation of black works of art was far more important then creating illuminating, if plaintive, autobiography. Still, Faulkner’s ideas on culture, class, and diversity shifted about. His fiction divided the white antebellum order between the high, noble Sartoris and the lowly, ignoble Snopes. But Walker notes that in Absalom, Absalom! Faulkner is unclear about the status of Thomas Sutpen, the newcomer to Yoknapatawpha County. His narrator concludes that Sutpen’s original sin was miscegenation (worse, we are told, than incest), although Walker points out that this word would not have been used in Sutpen’s time, only during the narrator’s. Interracial sex was not seen as a fundamental prohibition of slavery — it accrued that power only during Jim Crow. In that sense, Faulkner reinvented the Old South through the lens of Jim Crow, an approach that inevitably air-brushed away complex layers of class and race.

Robert Penn Warren and John Crowe Ransom. Photo: Kenyon College.

That was the sober Faulkner. In 1956, a drunk Faulkner insisted: “I don’t like enforced integration any more than I like enforced segregation. If I have to choose between the United States government and Mississippi, then I’ll choose Mississippi.” He described himself as both deeply loyal to Mississippi and a member of a “handful” of whites and blacks in the South who “believe that equality is important.” Faulkner later dismissed some of his contradictory comments as the products of intoxication. Walker focuses on Faulkner’s moderate “A Letter to the North” from the same year; however, it is likely that when Baldwin came to bitterly attack the “squire of Oxford” it was with Faulkner’s drunken bluster in mind, as well.

I have only mentioned a few of the fascinating interactions showcased in this book between writers of the period. Beginning with the Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown v. Board of Education, Walker ends his history of “southern pluralism” with another Supreme Court ruling, Regents v. Bakke. In that case, the Supreme Court upheld the University of California, Davis’s right to factor race into its admissions process. That judgment was written by a white Virginian, Justice Lewis F. Powell, Jr., who sided with liberal judges William J. Brennan, Jr., Byron White, Harry S. Blackmun, and Thurgood Marshall. The liberal judges, however, upheld the school’s affirmative action on the grounds of “past societal discrimination,” whereas Powell rejected such grounds as an attempt to legislate “heightened judicial solicitude” for one group or another. Powell invoked the words of President Andrew Johnson — on whose watch Reconstruction was halted and Jim Crow took root — suggesting to the court that African Americans not be made “special wards.” In fact, Powell dismissed the notion of racial homogeneity among the “white majority” as well.

What’s important for Walker is that an apparently un-Reconstructed white Southerner shared in the decision with his liberal colleagues; for Powell, the rights of institutions to constitute their membership as they see fit was in the best interest of “diversity” and academic freedom. Walker notes that this judgement was the end of a trajectory which began when the Southern Agrarian Donald Davidson denounced the war that “Northern imperialism” was waging against Southern diversity. Ironically, Powell’s words in the Regents v. Bakke judgment have taken on a life of their own over the decades: they have become the touchstone for generations of liberals who have sought to critique American society’s alleged fear of “diversity.”

Jeremy Ray Jewell is from Jacksonville, Florida. He has an MA in History of Ideas from Birkbeck College, University of London, and a BA in Philosophy from the University of Massachusetts Boston. He maintains a blog of his writings entitled That’s Not Southern Gothic.

It fell outside the scope of the work in question, but here’s an alternative assessment of the Agrarians (that I happen to agree with) from Will D. Campbell: “Nashville was deceiving itself. It thought that it was ahead, and it was, ahead of, say, Jackson, Mississippi, or Birmingham or Montgomery and so on, in terms of some leadership that did not want to be embarrassed by being haters and all that. But underneath that, you had some old aristocracy. The old Fugitive movement [a group of poets at Vanderbilt University], for example, was here. That was a racist movement. Actually, Donald Davidson [Vanderbilt professor of English; Fugitive poet, and Southern Agrarian], who was a fine writer, reporter, and others, I thought they had some good ideas when they talked about, you know, throw the radio out the window and take the banjo and the fiddle down off the wall. I thought that was cool. I still do. But, when it happened, why could not Donald Davidson, and I am using him as a prototype, or even others have said to Uncle Dave Macon and the Grand Ole Opry early-timers, say, hey, man, it would be cool, we will go down to the Ryman Auditorium [site of Grand Ole Opry], and you pick your banjo and you sing me mountain songs, and then I will read poetry. And let there be this fusion of folk and university culture. Instead of that, they moved to Belle Meade [a wealthy and exclusive suburb of Nashville] and didn’t read anything but one another’s [work]. They were embarrassed by the mountain, the rural people, the country music.”