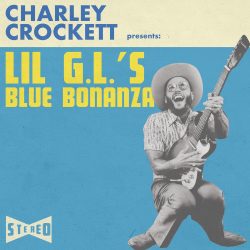

Country CD Review: Charley Crockett’s “Lil G.L.’s Blue Bonanza” — How Did We Get Here, Charley?

By Jeremy Ray Jewell

The unmistakable flavor of R&B can be found throughout Charley Crockett’s work

When the Huguenot de Crocketagne family came to Ireland from France at the end of the 17th century they changed their name to Crockett. In the next generation, the Crocketts would be landing in New York. From there they moved to Pennsylvania and northern Virginia, before, like many of their fellow Protestant emigrants from Ireland, the Crocketts would make it out to the frontier. In what would become eastern Tennessee they conflicted with the local tribes and joined the ranks of the Overmountain Men during the Revolution. And, of course, they would produce a son named David — you can call him Davy.

Back in that old eastern frontier the young Davy Crockett was variously employed as a cowboy and sold out for work to pay family debts. Named after a grandfather that had been killed by Creeks and Cherokees, Davy was a member of the Tennessee Militia during the Creek War under Andrew Jackson, whom he would often oppose politically, calling him “King Andrew” and a “greater tyrant than Cromwell, Caesar or Bonaparte.” Graduating through various ranks of public office, Davy built a reputation of defending poor settlers’ interests as an elected member of the Tennessee General Assembly before joining the US House of Representatives. Continuing his disdain for that ‘populist’ Andrew Jackson (born into an aristocratic frontier family), Crockett opposed the removal of the Cherokees. If Martin Van Buren were elected to continue the policy of the Indian Removal Act, Davy declared: “I will leave the united States for I never will live under his kingdom. before I will Submit to his Government I will go to the wildes of Texas. [sic]” And the rest, as they say, is history. But the story doesn’t stop at the Alamo.

The large modern city of San Antonio has emerged around the old Alamo mission and a lot has changed. The Tejanos watched as the gringos kept coming, some bringing black slaves with them. The first Cajuns who overshot Louisiana in the 18th century watched from the Gulf Coast. Amid that Francophone culture existed Creole culture and people with their own ideas about music, food, and race. And then there were the new immigrants: Czech, German, Jews (some Sephardic who fought in the Texan Revolution, others Ashkenazi who arrived after the Civil War). As America went, so went the Crocketts. Today we have Charley Crockett, musician and Texan. He is descended from Davy, but also from black American, Cajun, Creole, and Jewish folks. Crockett is a bluesman who purveys country and soul. He’s a remnant of our past, reared on hip-hop. A musician who has toured with Old Crow Medicine Show, and a busker in New Orleans, New York, and Paris. A man who has known his fair share of hitchhiking and lonely rough traveling, yet lives to sing and smile bright and wide for an appreciative audience. A little bit of that Texas panache atop a mess of “take ’em as they come” is being served up here by this good-time Charlie, who, as he says, can get blue now and then the same as you.

Crockett dedicated Lil G.L.’s Blue Bonanza to fellow Texan and traveling bluesman Henry Thomas (source of Bob Dylan’s “Honey Just Allow Me One More Chance” and Canned Heat’s “Going Up The Country,” to name only two). Thomas, from Big Sandy, Texas (near the aquatic sugarcane highway of the Sabine River), played a signature pan flute homemade from cane. Crockett, too, cooks up his own kind of country from homegrown ingredients. You can feel the influence of Tejano musician Freddy Fender and of Cajun and Zydeco styles, not to mention the horns and squeezeboxes which sometimes accompany Crockett. You can also hear the sound of Deep Ellum, Dallas’ Beale Street, from the days of Henry Thomas to those of Leon Bridges, contemporary Soul singer and friend to Crockett. And through it all there is a commitment to that kind of country that some had feared withered and died after the sleazy Golden Age of Nashville… no, not Alan Jackson, I’m talkin’ Jerry Reed and Roger Miller! Country that spoke to your shrinking paycheck, not addressed to some narrow prejudices from a boardroom.

Singer Charley Crockett. Photo: courtesy of the artist.

Perhaps that’s because of Crockett’s working-class roots, or perhaps it comes down to him from old Davy’s hatred of the ‘too big for their britches’ elite. Either way, his is the Country that resonates with “I hear ya, brother” back slap. In this regard, “That’s How I Got to Memphis” (written by Tom T. Hall, originally recorded by Bobby Bare) and “The Race is On” (written by Don Rollins, originally recorded by George Jones) stand out on Lil G.L.’s. Both tunes draw on the sad tale of someone uprooting themselves in order to bet their all on a chance to win big in love. The former’s migrant’s tale reminds us of the tenuousness of the denizens of the deeply rooted South, along the old Illinois Central railroad and Mississippi River, where entire cities have been generated out of wandering hopes, false-starts, and let-downs. Then again, another George Jones number, “Burn Another Honky Tonk Down,” tells us of the heartbreak faced by workers who do their best to provide for their partners while rejecting the vices that are meant to distract and/or placate them in their misery. Are ya listenin’, Nashville?

The blues song “Bright Light Big City” from Jimmy Reed and “Here Am I” from Ray Charles provide unmistakable evidence of how R&B informs Charley Crockett’s work. Case in point: Lil G.L.’s Blue Bonanza is the second of Crockett’s albums to carry the name “Lil G.L.,” following 2017’s Lil G.L.’s Honky Tonk Jubilee. The name was given to him as a reference to the ’50s R&B singer G.L. Crockett, whose tune “It’s a Man Down There” Charley gives a nod to on this album in his track of the same name. But, when all is said and done, what’s in a name?

It has been a while since the Crocketts left the “kingdom” of Martin Van Buren, but America has caught up with them. And while their wandering days aren’t likely over, we can at least share a campfire tonight. “Hey, ya heard this one?” we’re asked. “Not like that,” we answer.

Jeremy Ray Jewell is from Jacksonville, Florida. He has an MA in History of Ideas from Birkbeck College, University of London, and a BA in Philosophy from the University of Massachusetts Boston. He maintains a blog of his writings entitled That’s Not Southern Gothic.