Book Review: Memories of Buczacz — Jewish History from the Bottom Up

These extraordinary books from world-class writers are about reviving, through words, a now-derelict town and the lives of its ten thousand murdered Jews.

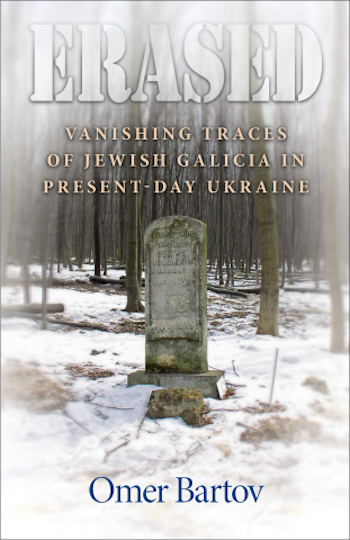

Erased: Vanishing Traces of Jewish Galicia in Present-Day Ukraine by Omer Bartov. Princeton University Press, 288 pages, $26.95

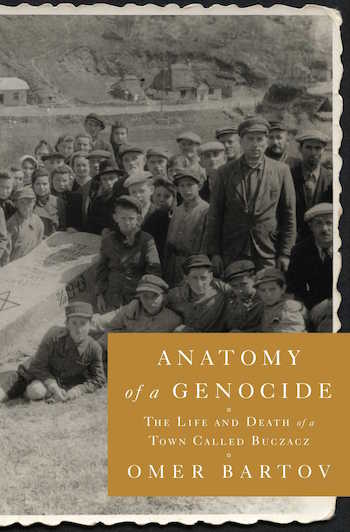

Anatomy of a Genocide: The Life and Death of a Town Called Buczacz by Omer Bartov. Simon and Schuster, 418 pages, $30.

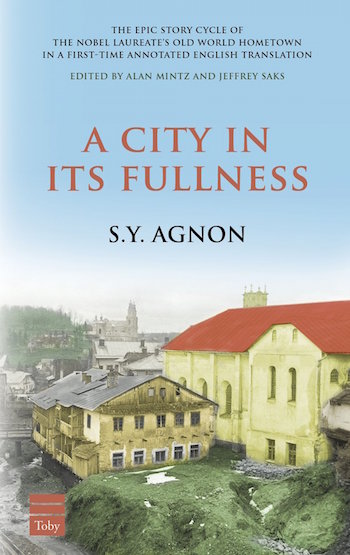

A City in Its Fullness by S. Y. Agnon. Toby Press, 617 pages, $29.95

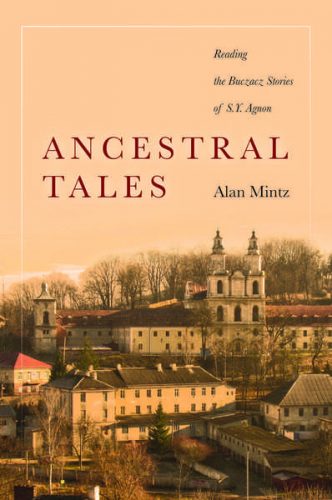

Ancestral Tales: Reading the Buczacz Stories of S.Y. Agnon by Alan Mintz. Stanford University Press, 440 pages, $56.99

By Susan Miron

I am lured into Hebrew prayer by two seductive two words, Mi-ha-yay ha-Mayteem (“Who gives life to the dead”), a phrase so controversial that the rational-minded German Jews who founded the Reform movement expunged the term, replacing it with “Who gives life to everything.” Two recently published volumes — one nonfiction, one fiction — attempt to give life to the murdered Jewish population in the small eastern Galician border town of Buczacz, now a shabby, ethnically homogeneous post-Soviet backwater in Ukraine. These are extraordinary books by world-class writers — a professor of European history at Brown University and an Israeli fiction writer who died in 1970. They revive, through words, this now-derelict town and the lives of its ten thousand annihilated Jews.

I closed my eyes, so that I would not see the deaths of my brothers, my fellow townsmen, because of my bad habit to see my city and its slain, how they are tortured by their tormentors in wicked and cruel ways. And I closed my eyes for another reason, because when I close my eyes I become as it were a master of the universe and see what I wish to see.

These touching lines from Agnon’s A City in Its Fullness are the epigraph for Israeli-born historian Omer Bartov’s Anatomy of a Genocide: The Life and Death of a Town Called Buczacz, a kernel of which was planted in his striking 2007 monograph Erased: Vanishing Traces of Jewish Galicia in Present-Day Ukraine. Anatomy of a Genocide was published this year, shortly after Agnon’s A City in its Fullness was finally translated into English, accompanied by Professor Alan Mintz’s trenchant study Ancestral Tales: Reading the Buczacz Stories of S.Y. Agnon. These three authors are deeply linked through their singular (perhaps near-mystical?) obsession with Buczacz, dubbed ‘a city of ghosts’ by Bartov, ‘a city of the dead’ by Agnon. (Mintz died suddenly, just before his book was to be published; he had planned on doing a lecture tour with Bartov.)

Any ardent reader of the Israeli writer Agnon will be aware of the importance of Buczacz; it was his birthplace as well as the site of much of his fiction. Buczacz began to buzz around my brain (again) as I read Bartov’s Erased, which told, via words and harrowing black and white pictures, the wrenching story of inter-ethnic relations in Buczacz and nineteen other small towns on the borderlands of Eastern Europe.

As he researched Erased, Bartov visited twenty now-Ukrainian towns — including Buczacz — only to discover “the merciless erasure of the postwar years,” the removal of any traces of Jewish life. Every opportunity to commemorate the Jewish people or recognize their extinction has been systematically overlooked: “buildings and cemeteries and burial pits, forgotten, expunged, grown over…. Present-day Buczacz, like all other towns in Western Ukraine, is almost entirely ethnically homogeneous…. There is no collective memory of either the presence or elimination of non-Ukrainians.” At times, he recalled in an interview in The Forward, “I could not avoid feeling anger, even rage, at the indifference, and sometimes outright malice, with which the relics of Jewish life are treated: the cemeteries turned into marketplaces and the synagogues used as garbage dumps, the unmarked mass graves and the staircases made of Jewish tombstones.”

As he researched Erased, Bartov visited twenty now-Ukrainian towns — including Buczacz — only to discover “the merciless erasure of the postwar years,” the removal of any traces of Jewish life. Every opportunity to commemorate the Jewish people or recognize their extinction has been systematically overlooked: “buildings and cemeteries and burial pits, forgotten, expunged, grown over…. Present-day Buczacz, like all other towns in Western Ukraine, is almost entirely ethnically homogeneous…. There is no collective memory of either the presence or elimination of non-Ukrainians.” At times, he recalled in an interview in The Forward, “I could not avoid feeling anger, even rage, at the indifference, and sometimes outright malice, with which the relics of Jewish life are treated: the cemeteries turned into marketplaces and the synagogues used as garbage dumps, the unmarked mass graves and the staircases made of Jewish tombstones.”

Completed halfway through Bartov’s work on Anatomy of a Genocide, Erased explores themes that have continually haunted this historian. Why in Holocaust studies, he asks, was there so little interest in how Jews had lived? The emphasis is always on how they had died, as if they had been brought into history for the sole purpose of their extermination. Why was so much weight put on “the final solution” of the Nazi regime and their agents and so little put on reconstructing the lives and deaths in the towns, in the ghettos, and in the camps: “It was as if the same Nazi insistence on separating the perpetrators and victims has also infected the historians writing about the period.” Why has almost every sign of Jewish life and culture vanished? Erased‘s black and white pictures, taken in each town, are heartbreaking. Anatomy also includes a profusion of indelible images; one is reminded of W.G. Sebald’s revelatory use of illustrations.

Anatomy was originally entitled The Voice of Your Brother’s Blood: The Murder of a Town in Eastern Galicia. For this volume Bartov traveled extensively through nine countries, negotiating nine languages as he excavated archives, examined thousands of rarely seen documents, and deftly recorded hundreds of first-person testimonies by victims, perpetrators, collaborators, and rescuers.

Bartov’s Buczacz undertaking was launched in Tel Aviv during 1995 over a pot of chicken soup in his mother’s Tel Aviv kitchen. Bartov was 41, his mother, Yehudit S.B., 71. His generation of sabras, born in Israel, sensed that their parents did not want to look back and discuss their youths, even if they were not actual survivors. After the founding of the State of Israel it became unfashionable for decades, even downright impolite, to ask survivors or even those who were not actual survivors about their life “over there.” In 1995, armed with a tape recorder, Bartov asked his mother — for the first time — to talk about her childhood. She had waited a very long time to speak about her adolescence, and for 90 uninterrupted minutes she told her son the story of her first nine years, happily spent mostly in Buczacz until, in 1935, she, her parents, and brothers moved to Palestine. (The rest of her clan, and Bartov’s father’s family, stayed in Europe — and vanished).

What intrigued Bartov was how his mother, though acutely aware of the murder of family members, preferred fondly recalling her Ukrainian friends, studying Polish in school, and speaking Yiddish at home. In an interview, Bartov wondered “What was it in a town like that — and there were hundreds of them — that made it possible for children growing up there to be quite happy in this multi-religious environment, and yet these same places produce so much resentment and rage and envy that when the time came people turned on each other.”

Most historians conceive of history through the eyes of the perpetrators, the powerful. Bartov prefers to see the past in a radically different way — from “the bottom up.” He researches a strata of people, most often the afflicted, who have traditionally received the least attention: “Assigning the victims to the category of ’the de-humanized’ or assigning the perpetrators to the category of ‘inhuman’ is an easy way out. The horror and tragedy of genocide is that it is an event in which human beings, who under other circumstances could and even sometimes did befriend or even love each other, are transformed into hunters and their prey.” Bartov strives to reconstruct what the traumatic event was like on the ground, as it was taking place, and to provide enough of its backstory to make it understandable. To do this, he combed through German court records, interviewed survivors and read their memoirs, letters, and personal testimonies. He was almost too late. By the time he finished the book, a twenty year undertaking, few of the survivors he spoke with were still alive.

Bartov has long attempted to understand the workings of genocide, particularly the attempt to exterminate the Jews of Europe in World War II (Murder in Our Midst, Mirrors of Destruction, and Germany’s War and the Holocaust: Disputed Histories). Bartov wanted to limn the difference between what he calls the “industrial killing” (of Jews) in Western Europe and the more intimate murders that took place in Eastern Europe, often among friends, family members, and once-friendly neighbors. Making sense of the latter demands a different concept of genocide: “In these little towns, at the corner of the world, this was no distant, neatly organized, bloodless bureaucratic undertaking, but a vast wave of brutal, intimate, and endlessly bloody massacres.”

Genocide generally takes place, as it has done in contemporary mass killings and in Buczacz, in communities where people know each other. It is, ironically, a social event. Someone is shot in the street; people decide to move into his apartment. How, Bartov asks, does this kind of violence become normalized? And why, afterward, do the killers show no traces of shame or guilt, while the victims feel both deeply? Most of the perpetrators, he notes, managed to wriggle out of a rickety, often corrupt judicial system and die peacefully in their beds. As Adolph Eichmann famously proclaimed during his Jerusalem trial, “Remorse is for little children.” “Perpetrators of genocide,” Bartov laments, “usually get away with murder.”

In Anatomy, Bartov surgically dispels many long-held historical assumptions and myths. One that surprised me (whose acquaintance with Eastern Europe was largely through fiction) is that the shtetl, where Jews lived apart from the rest of the population, was a myth. Life in towns such as Buczacz, Bartov insists, was premised on constant interaction between different religious and ethnic communities. The Jews did not live segregated from the Christian population: “The entire notion of a shtetl existing in some sort of splendid (or sordid) isolation is merely a figment of Jewish literary and folkloristic imagination. Integration was what made the existence of such towns possible. It was also what made the genocide there, when it occurred, a communal event, both cruel and intimate, filled with gratuitous violence and betrayal as well as flashes of altruism and kindness.” During the war, gentiles could shelter you, get food for you, or betray you: “You made choices all the time, even if it was a small choice.”

Bartov surgically dispels many long-held historical assumptions and myths. One that surprised me (whose acquaintance with Eastern Europe was largely through fiction) is that the shtetl, where Jews lived apart from the rest of the population, was a myth. Life in towns such as Buczacz, Bartov insists, was premised on constant interaction between different religious and ethnic communities. The Jews did not live segregated from the Christian population: “The entire notion of a shtetl existing in some sort of splendid (or sordid) isolation is merely a figment of Jewish literary and folkloristic imagination. Integration was what made the existence of such towns possible. It was also what made the genocide there, when it occurred, a communal event, both cruel and intimate, filled with gratuitous violence and betrayal as well as flashes of altruism and kindness.” During the war, gentiles could shelter you, get food for you, or betray you: “You made choices all the time, even if it was a small choice.”

For Buczacz’s Jews, survival depended on the relationships they had established with non-Jews. Most of the perpetrators were known as decent folk before the killings began: there is no evidence of past incidents of ideologically fueled violence or hatred. “Killers knew their victims personally,” writes Bartov, “and most of the time such familiarity only added to the sadistic glee with which they slaughtered children or buried entire families in mass graves… The murderers returned afterwards to resume their normal lives — there were no confessions of remorse or shame. The bloodshed seemingly left no stain.”

It is the centuries of peace that made the stunning breakdown of relations among the Ukrainians, Poles, and Jews so horrific. Jews began to settle in Buczacz in the 16th century. The oldest Jewish tombstone in the town cemetery dates from 1587. Before the war, around 8,000 Jews lived in Buczacz; about 2,000 Jews lived just outside it. Between October 1942 and June 1943, all of these Jews were murdered. The German authorities deported about half to the concentration camp at Bełżec. The other half were killed in Buczacz — on a major hill in the area or in its Jewish cemetery, both are a 10 to 15 minute walk from the center of town. Thousands of bodies still lie in these locations in unmarked mass graves. Given such intimate circumstances, with half of the Jewish population killed locally, there were no distanced “onlookers,” as there were in, say, Western Europe, when people could see hordes being pushed, with suitcases, onto trains, then disappearing. In Eastern Europe, Bartov insists, there was no systematic dehumanization. People knew each other, and their children, before they killed them. Their kids went to school together; they worked for each other; they knew each other from the marketplace.

Ethnic cleansing, Bartov asserts, rarely occurs as it’s portrayed in popular history. A different model for genocide occurred in Buczacz (as well as dozens of other small towns in Galicia):

In these little towns, at the corner of the world, this was no distant, neatly organized, bloodless bureaucratic undertaking after the quick ascent of a vitriolic political leader and the unleashing of military might, but a vast wave of brutal, intimate, and endlessly bloody massacres… It begins in seeming peace, slowly and often unnoticed, the culmination of pent-up slights and grudges and indignities. The perpetrators aren’t just sociopathic soldiers…. They are neighbors and friends and family. They are human beings, proud and angry and scared. They are also middle-aged men who come from elsewhere, often with their wives and children and parents, and settle into a life of bourgeois comfort peppered with bouts of mass murder: an island of normality floating on an ocean of blood.

“Many people,” Bartov explains, “think of the Holocaust as an event of industrial killing, symbolized by Auschwitz; a vast undertaking of streamlined, anonymous mass murder. In fact, half of the total victims of what The Nazis called ‘The Final Solution of the Jewish question’ did not die in extermination camps; they were killed in their own homes and streets, cemeteries and synagogues, in nearby hills, first and ravines. The killing was neither anonymous nor streamlined.”

Beginning in late June 1941, a small German force of merely 30 people, with the help of around 350 auxiliary police, engineered the murder of 60,000 Jews in the region around Buczacz. The Ukrainian police, assisted by the Jewish police, rounded up Jews and blocked escape routes. They took the Jews to hills where they had already prepared dug graves; there the Germans shot and killed their victims. Some observers recalled this happening on a weekly basis.

The townspeople could see and hear what was happening. Henriette Lissberg, the wife of a Nazi Landkommissariat, remembers the final action in February 1943; “I could observe the Jews being escorted up the hill past the Ukrainian police station and my house. I was standing by my door about sixty feet from the column of Jews. The distance to the actual ‘execution site’ was a mere 10-15 minute walk ‘from my house.’ There were men, women, and children of all ages. Once the Jews reached the hill, one could hear shots. Later that day, Henriette’s maid noted that the tap water had a strange smell and appearance. It turned out the water had been polluted by the mass grave on the hill, and residents were instructed to drink only soda water for the next few days.”

Historian Omer Bartov. Photo: Brown.edu.

What strikes Bartov is the “unbridgeable discrepancy,” the moral abyss, between the mundane prewar and postwar lives of the men who murdered the Jewish community of Buczacz, the astonishing brutality, callousness, and disdain for humanity that was openly displayed during the occupation. He is appalled that the West German courts’ (as of 2005) have investigated only 106,000 people for Nazi crimes. Of that number a mere 6,500 were sentenced — only 166 received life sentences. “Purely statistically,” he concludes, “each murder cost ten minutes in prison.”

In Erased, the historian responds to the barbarity succinctly: “We cannot bring back the dead, but we can give them a decent burial.”

Bartov has referred to S. Y. Agnon (1888-1970) as “the most famous Nobel Prize laureate that you’ve never heard of” — except, perhaps, for the German-Jewish writer Nellie Sachs, who shared the prize with him in 1966. He certainly has been the only Laureate to sport a black velvet yalmuke and speak Hebrew during the Nobel ceremony.

Agnon’s reputation among critics continues to grow, but he has had trouble finding dedicated readers (outside of academia) in either Hebrew or English. Generally recognized as the most important Hebrew language writer of the 20th century, he keenly felt the loss of his old readers. “There were many, but the six million Jews that Hitler killed — the sages and writers and artists and modest readers who would sit and read and enjoy each and every other word, who would not make themselves conspicuous, and not say, ‘Here! I am your reader!’ These are missing.” Things have not really changed since this lament.

Agnon described his use of Hebrew in his fiction as “the language of all generations that preceded and of all the generations to come.” Notoriously thorny to translate, Agnon casually amalgamates a diverse linguistic strata: the Bible, Mishnah, Talmud, midrash, prayerbook, medieval Hebrew poetry, rabbinic commentaries and Eastern European Hassidic tales. As critic Robert Alter summed it up deftly in the New York Review of Books: “His Hebrew is essentially the Hebrew of the early rabbis, which means the Hebrew of the Mishnah and the Midrash compiled early in the Common Era, with at some moments a trace of Yiddish inflections and occasional limited concessions to the modern language. His hyperbolic invocation of ‘the language of all the generations’ reflects his classicizing bent: for him, rabbinic Hebrew is as living and subtly expressive a vehicle as it was eighteen hundred years ago, and by using it he means his works to be similarly long-lasting.”

Tellingly, Agnon once apologized to an interviewer for not speaking English. He told him in Hebrew:

I have been sitting in Palestine nearly 60 years — during that period I was also in Germany — but since I returned it’s 44 years. During all those 44 years I could have learned English. But I made a contract with the Almighty, that for every language I did not learn He would give me a few words in Hebrew.

Agnon finally settled down in Jerusalem after many years as a wandering Jew. He left Buczacz for Palestine in 1908 and spent many years with the community of the Second Aliyah. In 1912, he left for an extended sojourn in Germany to round out his education and experiences. When he received word in 1913 that his father was dying in Buczacz (then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire) he rushed to get there but did not arrive in time for the funeral. (His stories are full of delays). He stayed on in Germany until 1924, returning to Palestine after a fire destroyed his home, incinerating his library of rare books as well as manuscripts of two nearly completed books, a long autobiographical novel and what was meant to be his contribution to Martin Buber’s anthology Hasidic tales. In 1930, he again left the land of Israel after his home accidentally burned down. He stayed in Berlin, where he saw the first printing of his collected works by the publishing house of Schocken; he then traveled to Poland for a week, and then spent a week in Buczacz, his only substantive visit since he left at age 20. He wrote to a friend that the inhabitants might well have read his books and modeled their lives accordingly, so closely did they resemble his fictional creations.

In dramatizing Jewish life, Agnon immersed his imagination in the trio of social environments he had personally experienced — Eastern Galicia (Poland), the land of Israel, and Germany, with both Buczacz and Jerusalem often serving as his focal points. Agnon located several of his books in the region of Buczacz — The Bridal Canopy (1931), A Simple Story (1935), and A Guest for the Night (1939). Szybucz, Agnon’s fictional name for Buczacz, means “muddle” in Hebrew, implying it is a place where life has broken down. Revealingly, in the 160 stories he wrote for 1973’s A City in Its Fullness, (Ir u-Melo’ah) he dropped the pejorative and referred to the town as Buczacz.

The largest and most ambitious of Agnon’s post–World War II publications, the epic volume includes folktales, legends, chronicles, and other forms of narrative. Agnon’s mission: to preserve a way of life that had been rendered extinct. His literary timing was unfortunate. While he was “building a city,” Israel was preoccupied with welcoming in exiles and building a state; the fledgling nation was hardly interested in looking back at the sweeping catastrophe that had extinguished the Jews’ European past. Worse, it was also the eve of the Yom Kippur War, not a propitious time to embrace a repository of stories about a dead town in Galicia, no matter how splendid this capacious palace of memory was.

In the ’50s, countless memorial books were being assembled about the annihilated European Jewish communities. Agnon’s friend Israel Cohen worked on the Buczacz investigation for ten years (without the help he had hoped for from his friend), who was busy creating his own distinctive Buczacz memorial. In Ancestral Tales: Reading the Buczacz Stories of S.Y. Agnon, Mintz explains the disconnect:

The accounts of Jewish communal life in these books generally focus on the several decades before the war … whereas Agnon was after a classical past that was beyond the range of such reminiscences. A memorial book explicitly saw its function to become a matseivah, a gravestone in words for a lost community, whereas Agnon sought imaginatively to recreate a spiritual vigor it once possessed.

For Agnon, storytelling was the only path towards accomplishing these goals; documentation and testimony about the past was for other people to collect.

S. Y. Agnon. Photo: Wiki Commons

Like Bartov, Agnon felt compelled to write a “biography” of Buczacz that was primarily intended to be a metonym for the extinguished world of Eastern European Jewry. During the last fifteen years of his life Agnon quietly published tales from A City in Its Fullness in the Israeli newspaper HaAretz. Because he chose to write a Jewish history via the mode of fiction, Agnon gave himself the freedom to set his Buczacz stories over an expansive time period, from the Khmelnytskyi massacres of 1648 to the emancipation of European Jewry in 1867. According to Mintz, “this patchwork of stories mixes up long and short texts, conventional narratives along with ethnographic essays. Narrators invite other narrators to share center stage” — its characters include illustrious historical figures as well as fictional figures.

The Hebrew version of A City in Its Fullness (710 tightly packed pages) was published three years after Agnon’s death and remains mostly unknown in Israel. The English edition features 140 stories (mostly the longer and most literary yarns) and is deftly edited by Jeffrey Saks and Alan Mintz. An inveterate rewriter, Agnon didn’t live to specify the order of stories, or to do his customary meticulous editing. This task fell to the writer’s daughter who, significantly, placed one of the most important stories, “The Sign,” at the end of the book’s Hebrew edition.

Mintz felt strongly that “The Sign” should open the book. For him, the volume’s texts “are an amalgam of storytelling, ethnographic information of the history and customs of Buczacz…. For many decades since its publication, A City in Its Fullness has been regarded… as a work that is not exactly literature but more resembles a repository of proprietary nostalgia, historical arcana, and familial anthropology. My wish is to make a case for the work containing some of the greatest fiction Agnon ever wrote, fiction that deserves not only to be given a place in the Agnon canon but to reshape it.”

The story that triggered the editorial contention begins “In the year when the news reached us that all the Jews in my town had been killed, I was living in a certain section of Jerusalem, in a house I had built for myself after the disturbances of 1929.” The calamity of Buczacz’s Jews in the ’40s sneaks into many of the introductions to these texts, even though they are set centuries before. In “The Sign” an Agnon-like narrator, who lives in postwar Israel, receives a mystical visitation from the famed medieval poet Solomon Ibn Gabirol. Mintz argues that the eerie text is a gateway story that proclaims Agnon’s grand aesthetic ambition: to build the city anew through the resources of his own imagination rather than merely performing a commemorative gesture. A City in Its Fullness‘s slow accretion of tales was dedicated to recreating the vanished world of European Jewry — not memorializing the dead, but bringing them back to life, if only on the page.

— This essay is dedicated to Cynthia Ozick.

Susan Miron, a harpist, has been a book reviewer for over 20 years for a large variety of literary publications and newspapers. Her fields of expertise were East and Central European, Irish, and Israeli literature. Susan covers classical music for The Arts Fuse and The Boston Musical Intelligencer.

Tagged: A City in Its Fullness, Alan Mintz, Anatomy of a Genocide: The Life and Death of a Town Called Buczacz, Ancestral Tales: Reading the Buczacz Stories of S.Y. Agnon, Buczacz, Omer Bartov

Excellent, wide-ranging and moving review. I’ve shared it with friends who’ve let me know how much they appreciated reading it. Hope to read more literary essays from Susan Miron.

A beautiful essay in its range and tone. Agnon was a favorite of my father and I remember his excitement when Agnon and Sachs won the Nobel. What is most important though is the distinction Susan emphasizes between the industrialized killing and the intimate killings described in these books. That is most chilling and why these books must be read by anyone interested in the history and literature of the 20th century.

Wow. I’m used to viewing our history as sad yet elevating. This piece was so achingly sad and moving. It’s bound to inhabit my consciousness for a long time to come.