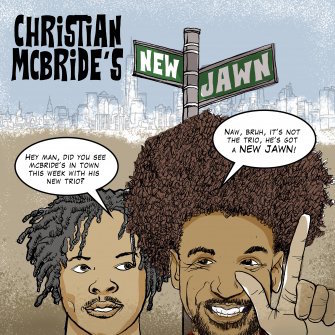

Jazz CD Review: Welcome Christian McBride’s “New Jawn”

One of the distinguishing characteristics of this set is the smart, energetic, and ever-changing, relationship between bass and drums.

Christian McBride’s New Jawn (Mack Avenue)

By Michael Ullman

My friends from Philadelphia use the word “Jawn” to mean just about anything. Bassist Christian McBride uses it to describe his new band, a quartet with trumpeter Josh Evans, saxophonist Marcus Strickland, and drummer Nasheet Waits. There is no pianist, which has the interesting effect of pushing the bass and drums to the forefront, where they flourish. In fact, one of the distinguishing characteristics of this set is the smart, energetic, and ever-changing, relationship between bass and drums.

The disc begins with McBride and drummer Waits playing McBride’s amusing composition “Walkin’ Funny.” McBride plays four beats of a walking bass line over Waits’ steady drumming. Then there’s a kind of hiccup, as if the harried walker fell off the curb. It is, as the composer suggests, funny, and it forces the horns in their solos to create different kinds of lines, more tense perhaps, than a walking background might ordinarily suggest to them. Through all the rhythmic eccentricity, McBride and Waits seem to anticipate each other’s moves.

Everyone is a composer in this band: each member proffers two pieces. (The last number is by Wayne Shorter.) I find Nasheet Waits’ “Ke-Kelli Sketch” particularly intriguing. It begins with a growling series of phrases bowed deep in the bass by McBride. He hardly plays a tune: it is rather a grumbling, increasingly agitated commentary (or so it sounds to me) on Waits’ drumming. Waits’ piece grinds almost to a halt at the end of this section; then the horns enter with a single held note played in unison. Suddenly McBride is plucking furiously in a little circular pattern over which the two horns play a kind of slow moving melody. Then Evans starts to solo with a short phrase that he repeats. There are no long, Clifford Brown-esque lines here. The space the soloists leave suggest the intensity with which they are relating to the bass and drums. Not everything is agitated, nor does the piece sustain only one texture.

Josh Evans’ Ballad of Ernie Washington is as relaxed as Waits’ piece is frantic. The main phrase of Strickland’s upbeat “The Middle Man” reminds this listener of Bob Dorough’s “Nothing Like You”: it bounces along merrily. Waits’ “Kush” is played with rich aplomb by trumpeter Evans. It’s a gentle, sweetly flowing piece that demands bluesy solos from both horns. McBride’s bowed solo on this piece unfolds over another surprise: the held notes of Strickland on bass clarinet.

Bassist Christian McBride. Photo: Mack Avenue.

Like the original recording on the fourth side of 8:30, McBride’s version of the Wayne Shorter composition “Sightseeing” begins with a short drum solo. Then the tune’s deliberately awkward, stop-and-go melody — played by the two horns — arrives in a rush. The theme is a series of staccato pokes; I think it might have been written as a test for Weather Report’s bassist Jaco Pastorius. Then something remarkable happens: Strickland begins a spare solo (he might be thinking of Wayne Shorter here) and McBride halves the tempo of his accompaniment. Suddenly what was intense and compact becomes … spacious. At one point Strickland and McBride repeat (three times) the same lazy three note phrase. The piece picks up and subsides repeatedly. Sometimes dictated by the soloist, whether Strickland or Josh Evans. Sometimes, I believe, by the rhythm section of McBride and the remarkably subtle, vibrant, and ever responsive Waits. At time, McBride’s virtuosic solo sets off a conversation between his bass and Waits. It’s a remarkable performance — agile, big-toned, and rhythmically complicated. He slows down almost to a stop at the end.

New Jawn is a varied set by a band made up of virtuoso listeners as well as players. Their interactions range widely — complex at times, simpler at others — but always fascinating.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for The Atlantic Monthly, The New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, The Boston Phoenix, The Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. (He plays piano badly.)