Film Review: “Free Solo” — Mountain Masterpiece

As Alex Honnold observes, if he solos El Cap, it’s like winning a gold medal in the Olympics. But there’s no second or third place. If he fails, he dies.

Free Solo, directed by Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi and Jimmy Chin. Screening at Coolidge Corner Theatre, AMC Loews Boston Common, ShowPlace ICON at Seaport with ICON-X.

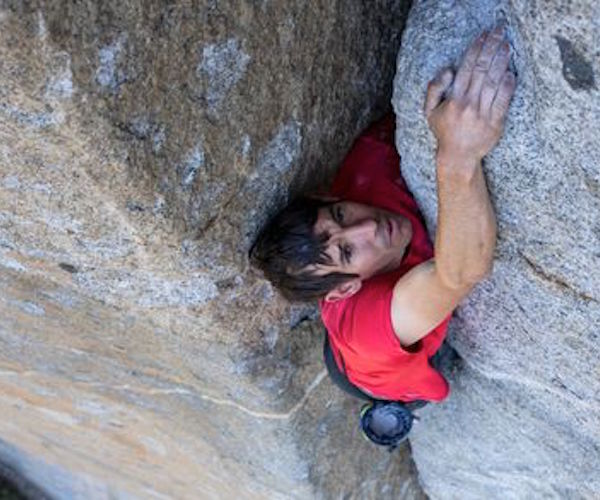

Alex Honnold in a scene from “Free Solo.”

By Jay Atkinson

Even in documentary films, a “nonfiction” story is often refashioned, reshaped, and repurposed, scene by scene, with an eye toward the satisfying rigors of the narrative arc. The camera doesn’t see everything—it sees the right things, in order to build up sympathy, or enmity, for the protagonist.

But Free Solo filmmakers Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi and Jimmy Chin didn’t require as much rearranging as most producers to create the rising action in their new film. This tense, engaging, brilliantly photographed cliffhanger depicts world-class rock climber Alex Honnold’s attempt to “free solo”—climb without ropes, or safety harness—the treacherous 3,000-foot Dawn Wall of El Capitan in California’s Yosemite National Park.

In traditional narrative, the protagonist and antagonist face off, with one prevailing over the other. Honnold’s creative problem solving, dedicated training, and single-minded focus give Vasarhelyi and Chin the perfect subject — and the ideal adversary — to demonstrate the lasting value of a great story.

More than once, Honnold, 32, a confident, almost detached fellow, says that he’s a “warrior,” although his manner reflects the peaceful interiority of a great dancer or jazz musician. Through his meticulous preparation, as well as the climber’s meditative approach to the challenges and dangers of the task before him, Honnold embodies Ernest Hemingway’s dictum of “grace under pressure” more convincingly than any Hollywood movie star ever dreamed of.

Honnold’s quest, the culmination of many dangerous, difficult, and strenuous ascents, is the perfect embodiment of four basic types of narrative conflict—man vs. man, man vs. himself, man vs. nature, and man vs. society. A quiet, existential hero, Honnold’s personality seems to consist mainly of his iron resolve to solo El Cap. Although he has honed his climbing technique to a razor sharp and balletic style that makes it appear he is flowing up the rock, defying gravity and physics, his biggest obstacle is an internal one. If he makes a single, quarter-inch mistake, he will fall to his death.

One of the most intriguing parts of Free Solo is Honnold’s Zen-like effort to conquer his fear, “stepping outside it,” as he says. El Cap is massive, monumental, a giant tombstone for all the daring and dead adventurers who have failed there. The wall is frighteningly smooth for many long stretches, dimpled with treacherous overhangs and dark, ominous cracks and fissures. It looms up, primordial, unconquered, terrifying—Nature, red in tooth and claw—or perhaps, an embodiment of the fifth type of narrative conflict, man vs. God. Trying to free climb such an Old Testament monolith can be viewed as an insult to its Maker.

Honnold faces all these difficulties while eschewing social conventions. He wears the same shirt nearly every day, living in his van near the base of the rock and eating his meals straight from the frying pan. During a visit to his old high school, he admits that he often got in trouble for climbing onto the school’s roof. When a grinning teenager asks how much money he makes, Honnold says that he lived on a shoestring for years, though corporate sponsorships now provide an income equivalent to a “moderately successful dentist.”

Brusque and charismatic, Honnold prepares for his star turn by occasionally using ropes and a harness, mapping out possible routes one pitch at a time, and dogged by cameras that sometimes intrude on his planning and his mood. At one point, he abandons a first attempt at the solo—it felt like he was performing for the cameras. In a telling sequence, one of his friends, also a world class free climber, congratulates Honnold for walking away from the climb. He even says there’s no shame in abandoning the feat altogether. But Honnold assures him it just wasn’t the right day—he’s going to try it.

Throughout the film, Honnold takes a low-key, DIY approach to a feat that may—or may not—result in the greatest achievement in the history of his sport. It’s fair to say that soloing El Cap is equal to, or greater than, Roger Bannister breaking the four-minute mile, or Boston Red Sox outfielder Ted Williams batting .400. As Honnold observes, if he solos El Cap, it’s like winning a gold medal in the Olympics. But there’s no second or third place. If he fails, he dies.

Jimmy Chin and Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi made another wise move—I’m being serious here—by remaking Howard Hawks’ 1939 film, Only Angels Have Wings. In that movie, Hawks, a former aviator and racecar driver, created a dark, atmospheric thriller about a fictional airline in the early days of commercial flying. Cary Grant, playing against type, stars as the ace pilot and manager, responsible for a motley crew of flyers and a yard full of balky, balsa wood planes. Charged with flying the mail over the Andes Mountains in the years following the Great War, he’s relentless, often going with little or no sleep and sending both himself and his friends on increasingly dangerous missions.

Cary Grant and Jean Arthur in “Only Angels Have Wings.”

When a popular young pilot is killed in a botched landing, a vacationing showgirl, played by Jean Arthur, is horrified when the other aviators go on drinking and carousing right after the crash.

When Arthur scolds the group because their friend Joe is dead, each aviator, in turn, asks, “Who’s Joe?”

Grant, obviously a surrogate for the dashing Hawks, explains that Joe died because he “wasn’t good enough.” He failed because he lacked the right combination of airborne athleticism merged with that certain something—an ineffable quality that makes some individuals wilt, and others thrive, in perilous situations.

In Free Solo, Honnold plays the Grant character, likeable, charming, but essentially inscrutable. Just like coal miners, cops, fire fighters, and soldiers, people die frequently in Honnold’s line of work, many of them his close friends. (Several of these climbers are shown in photomontage, free-spirited and smiling young men who felt the same way about soloing as Honnold does—Each climb might be my last.) But Honnold accepts the dangers and the losses, some of them deeply personal, and moves on, just like Grant in Only Angels Have Wings.

If you’re familiar with Hawks’ oeuvre, and Only Angels Have Wings in particular, the parallels are striking. Complicating things at the airfield, Rita Hayworth, Grant’s old flame, arrives on the scene with her new husband, a previously disgraced pilot looking for a job. Like Hayworth, Arthur has set her cap for Grant, despite his best friend’s warning that she should stay away from him. In Free Solo, Honnold’s girlfriend, Sanni McCandless, a smart, thoughtful young woman, plays the Jean Arthur character, though she’s even more lovely, luminous, and innocent than Arthur, a sought-after leading lady in the ’30s.

As the couple grows closer, you can see McCandless trying, subtly at first and then more forcefully, to convince Honnold to choose their relationship over his passion for free soloing. As much as anything, Free Solo is a love story—McCandless loves Honnold and he loves her, though not as much as he loves climbing.

In a scene that could have been lifted straight from Jules Furthman’s screenplay for Only Angels Have Wings, Honnold sits beside McCandless, listening impassively as she finally asks if he’ll choose soloing El Cap over her. His reply is both touching and chilling—he would be sad if she left him, but he can always find another relationship.

In a telling interview with Honnold’s mother, Dierdre, who admits she was a distant, sometimes cold parent, we learn that Alex’s late father, Charles, who introduced his son to climbing, was probably on the Autism spectrum, though undiagnosed. Suddenly, Honnold’s plainspoken manner and implacability begin to make sense. High functioning autistic people are often extremely intelligent, focused on a single field of expertise, and unable to read certain social cues.

To his credit, Honnold has made an effort to share more of his feelings with McCandless. When she opens up to him, and he makes it clear that he’s going to free climb El Cap anyway, you see something stirring in his eyes.

Earlier, he’d said, “Nothing good in the world happens when you’re happy and cozy. It’s about being a warrior.” But when McCandless bares her soul, Honnold, in a heartrending gesture, leans over and thanks McCandless for her concern.

On June 3, 2017, Alex Honnold woke up and decided he was ready to solo El Cap. Previously, he’d told the camera he wasn’t going to let McCandless know in advance of his attempt. Earlier in the film, he’d informed her, “When you say ‘be safer’, I can’t.” Only Chin and his crew, and a few climbing friends, know what Honnold is doing.

After Honnold’s mild complaint, Chin and his team of rock climbing cinematographers backed off a little, using a combination of drone photography, tiny cameras planted along Honnold’s route, and others operated by cinematographer-climbers in harness.

As Honnold begins climbing, an astonishingly unimpressive figure armed only with a pair of climbing shoes and a bag of chalk, one of his friends down below remarks that despite his reputation and talent “people who really know climbing” are freaked out by news of this attempt.

Alex Honnold in a scene from “Free Solo.”

Only one moment in the film seems inauthentic, a gesture toward the audience that has a Reality TV feel to it. Talking to the camera, Chin looks sad and serious, noting that he’s conflicted about shooting Honnold’s solo on El Cap. But there’s never any doubt that he’s going to make this movie, and the scene could have been cut without sacrificing any part of what’s at stake for Honnold and his loved ones.

Watching Honnold ascend, sometimes weaving back and forth across the rock face, and other times worming his way up a long, vertical crack, two things sprang to mind—I can’t believe he’s not using a rope and It looks easy and improvised but it’s really years of practice, mistakes, losses, and setbacks.

Earlier in the film, climbing with a rope and accompanied by the camera crew, Honnold attempted to solve the “Boulder Problem,” a seemingly impossible passage about two thirds of the way up the rock. First, he tried a “karate kick,” clinging to a knife-edge of rock with one hand, while scissoring his left leg across the chasm and trying to get a foothold. That failed, leading to a short fall, where he dangled from the rope, swinging back and forth.

Honnold climbed back up and attempted a different move. This time, he held onto the rock overhead with the fingertips on both hands, swung his body like a pendulum, and leaped away from the rock and sideways, trying to find another finger hold on the fly. Again he failed.

Now, as he attempted to surmount the same obstacle without a rope and safety harness, one of the cinematographers aimed his camera but looked away, stricken. “This is just so gnarly,” he said. A moment later, my companion in the theater, an adventurous woman who’s no stranger to outdoor challenges, whispered, “This is the scariest movie I’ve ever seen.”

And one of the most enthralling moments in cinema I’ve ever seen.

Honnold finished his solo climb of El Capitan in three hours, fifty-six minutes. It was a messy yet flawless effort, like witnessing Van Gogh painting “Starry Night,” or Charlie Parker blowing a mad solo on his saxophone.

At the top, surrounded by members of the crew, Honnold did not exult. He sat on the edge of the cliff, his arms hugging his knees.

“So delighted,” he said. A few moments later, he said it again. That was it.

Honnold finished his climb before the sun was high in the sky. Most people would’ve rushed out for some champagne. But Honnold headed back to see McCandless, and to work on his finger strength by using the hangboard in his van.

Jay Atkinson’s eighth book, Massacre on the Merrimack: Hannah Duston’s Captivity and Revenge in Colonial America, won the 2016 Massachusetts Book Award Honors in Nonfiction. He’s been nominated for the Pushcart Prize four times, and teaches writing at Boston University. You can e-mail Jay at jaya@bu.edu, or follow him on Facebook or Twitter.

Tagged: Alex Honnold, documentary, El Capitan, Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi, Free Solo, Jimmy Chin

Excellent review! I’d add that Honnold said of McCandless, “she makes everything better”. While Honnold is completely riveting in his relentless pursuit of El Cap it was also a tribute to the respect both individuals had for each other’s goals and desires, and the way they managed the extreme fears that go along with free soloing that made it emotionally engaging all the way through.

In his review, Jay Atkinson accurately captured the blind passion of climbing. The adrenaline high that lifts the athlete above the ordinary mortals. So happy that Honnold’s love of climbing, the hard work he put into it and the risk that he took were rewarded by this incredible success!!!

Very powerfully written. We decided to read it in its entirety in the latest Arts Fuse podcast episode