Jazz Commentary: Chet Baker — The Climax of Cool

For most of its history, jazz has been a macho culture. Sexual ambiguity or gay-ness were subjects of derision.

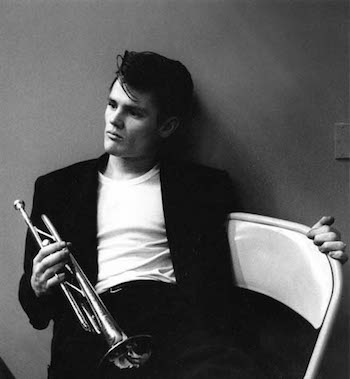

Young Chet Baker. Photo: JazzLabels.

By Steve Provizer

We think of the 1950’s as a time of relative social conformity and fixed gender identities. But, in fact, major cultural shifts were underway. Male stereotypes were being unpacked and, to some degree, unfrozen. Where films and music once gave us male characters that were either hyper-macho and worthy of respect or limp-wristed objects of derision, male characters and performers who could express emotional vulnerability began to emerge. In film, James Dean personified this shift. In music, it was Frank Sinatra and Chet Baker, who both created music with a heightened sense of male emotional vulnerability. However, a closer look shows that Baker made a more radical break with male stereotypes.

Sinatra, with his arrangers Billy May and Nelson Riddle in In the Wee Small Hours (1955) and Songs for Swingin’ Lovers! (1956) bridged a gap in popular music. They showed that songs could swing and still deliver an intimate romantic message. To that degree, Sinatra did stretch male stereotypes, but he remained within the boundaries of older, explicitly macho imagery, a scion of the “crooner” tradition that began with Bing Crosby and continued through swing era singers like Ray Eberle and Vaughn Monroe. Chet Baker, however, pressed towards an androgyny that upended this imagery and this got a surprising amount of traction in American culture.

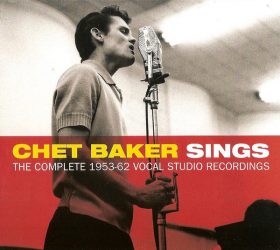

Stylistically, Baker was also a successor to the style first espoused by Bing Crosby in the late ’20s. Chet Baker’s style of singing on Chet Baker Sings (1954) finished off what Crosby started. The latter had initiated the movement from “hot” to “cool” by teaching singers how to generate a more intimate sound by using the microphone. However, although Crosby’s style was relatively laid back, he still used “hot” techniques, such as vibrato, slurring, and small ornamentations to “sell” the tune. This continued to be the standard, but Baker took coolness several steps further, either eliminating or dramatically taking down the heat of these techniques. Also, in the timbre of his voice, he did not sound like a man singing was supposed to. And, unlike Crosby, whose voice lowered into a comfortable baritone, Baker’s voice never varied as he aged. From the start, fellow musicians, friends, and critics were negative. It took guts, and possibly some measure of obliviousness, for Baker to shut these voices out and continue to sing.

There was nothing strange about the idea of Baker, as a trumpet player, taking up singing. He took his place in a long line of jazz trumpet players who sang. Louis Armstrong, Jabbo Smith, Roy Eldridge, Bunny Berigan, Louis Prima, Hot Lips Page, and Dizzy Gillespie were all proficient vocalists. They thought of themselves as entertainers, liked to vocalize, and were happy to give their chops a break. Almost all these guys specialized in a ballsy approach, sometimes ironic or sly, often bluesy. Armstrong had romantic tunes in his repertoire, but there is an artfulness in play that separates the singer from the object of his affection. In the later phases of his career he sang with great tenderness. Berigan’s style was lighter than the others. Tellingly, even after he had a hit with “I Can’t Get Started,” he almost always deferred to a band singer, content to play. Baker’s singing style was the first in this lineage that said out loud: “This is what it means to be vulnerable.”

As with the other trumpet player-singers, there was a strong connection between Baker’s instrument and his voice. His playing was distinguishable from, but similar to, the approach of others in the ’50s, like Jack Sheldon, Don Fagerquist, Don Joseph, Tony Fruscella and John Eardley. Of these, only Sheldon also sang. His voice was better than Baker’s, but his singing style ranged from cooing drollness to belting. To Sheldon, romantic meant sexy, while Baker was never so indiscreet, or overt. His sexiness was hidden below layers of romanticism and self-protection.

Rhythmically as well as in note choice, Baker’s singing paralleled his playing. But the fragility, tremulousness, and high tenor range of his voice amplified the tune’s vulnerability. The only voice like it belonged to (Little) Jimmy Scott, who had a hit in 1950 with Lionel Hampton’s “Everybody’s Somebody’s Fool” and who showed up in that same year with Charlie Parker, singing “Embraceable You.” But, although his voice was as “non-masculine” as Baker’s, Scott sang with all of the heat that Baker eschewed.

Reading about Baker’s foray into singing is like wading into a critical abattoir. As noted, almost no one liked it — musicians, friends, or critics.

There are conflicting stories about how Baker’s vocals were initially recorded. Some insist that the trumpeter demanded it and the owner of the Pacific jazz label, Dick Bock, balked. Others say that Bock wanted it and Baker resisted. Either way, Baker’s inexperience (or ineptitude) made for innumerable retakes, marathon sessions, and a lot of audio cutting and pasting.

Two musical elements were not subject to carping. One was Baker’s phrasing, which rhythmically paralleled his adept playing. The second was his scatting note choice, which reflected the melodic gift he displays in his trumpet solos. As for the criticism, Baker was accused of singing out of tune. I’m pretty sensitive to people staying in tune and I don’t hear the problem often, except on some held notes — the hardest to sing in tune, and beyond his vocal support system.

Naysayers also blasted Baker’s lack of affect, charging that it lacked emotional weight. This accusation was often accompanied by an analysis of Baker’s life choices — drug use and callousness toward women. People like the artist’s life to harmonize with the qualities they find in the art — and both positive and negative projections about Baker were intense. He was worshipped and reviled. Some thought he sang and looked like an angel. Others saw him nod out or heard about him acting like a cad and detected that in the music (Such critiques were not unknown to Sinatra, as well).

What I think made critics, fellow jazz musicians, and many men particularly uncomfortable is that Baker didn’t sing like a man. Much was made about the girlish, non-masculine quality of his voice. I’ve heard people ask, when they’ve heard Baker sing, whether it was a man or a woman. He has a light tenor voice, not dissimilar in range to people like Nat Cole or Mel Torme. But Baker’s voice was all “head” and no “body.”

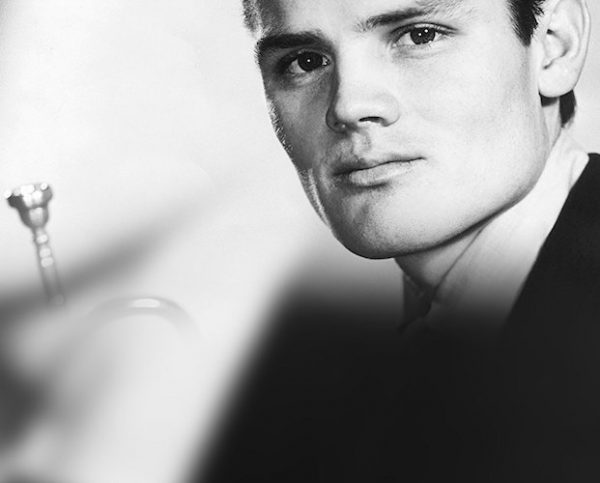

For most of its history, jazz has been a macho culture. Sexual ambiguity or gay-ness were subjects of derision. Baker was heterosexual, but for him to sing the way he did was almost, in a sense, to “come out.” Of course, Baker wasn’t consciously making a political-sexual point. When he responded to interviewers who challenged his masculinity, he made certain to reaffirm that he liked girls, not “fellers.”

Trumpeter/singer Chet Baker — When he responded to interviewers who challenged his masculinity, he made certain to reaffirm that he liked girls, not “fellers.”

Moving from just playing the trumpet to becoming a jazz vocalist/leading man while grappling with the negative response from critics as well as from fellow musicians did not make continuing to sing easy. It is not clear as to whether Baker was or was not using heavy drugs before Chet Baker Sings, but there’s no doubt that he became more deeply enmeshed in heroin and speed during this period. There is a strong possibility that drugs, as well as the incredibly strong response by women to his singing, were two key elements in helping Baker weather the brickbats and continue to sing.

Baker’s repertoire was standards and the great American Songbook. It’s appropriate that the most famous of his vocal renditions is of “My Funny Valentine.” In this Rodgers and Hart tune, we have a perfect match of performer and song. This is a song that spells out the imperfections of the lover (“is your figure less than Greek, is your mouth a little weak, when you open it to speak are you smart”). Examine the title itself — my “funny” valentine. The conceit is not that the lover is funny/humorous, but funny as in-how did this happen-how did I end up with someone like you? This is love as mystery, song as mystery, sung by a musician whose life was lived publicly, but who was himself enigmatic. Yes, we know the biographical facts of Baker’s life, but his inner life was shrouded in layers of romanticism, self-protection, and listeners’ projections.

It’s difficult to talk about Baker’s influence because he didn’t overtly inspire a generation of male singers. Most tenor-range jazz vocalists remained more beholden to older approaches. Jimmy Scott, Tony Bennett, Johnny Mathis, Mose Allison, Oscar Brown, Jr., Mark Murphy, Jackie Paris, and Sammy Davis, Jr. were all much “hotter” singers.

But I contend that Baker significantly changed the psychic and cultural “field,” and in so doing influenced those singers and others who came after. He brought the ethos of cool to a revelatory climax, moving into territory that had once belonged only to female vocalists. He opened up the emotional palette of male singers. They had previously shied away from vulnerability — now they were more likely to draw on that emotion.

Revealingly, Baker remained completely un-ironic as a vocalist. He always sounded sincere — never a wink or a nudge. So the singer was a paradox: a drug addict and philanderer, Baker created considerable distance between himself and others, yet he transmuted this distance into a kind of intimacy that had rarely, if ever, been expressed in the pop-jazz male voice.

Steve Provizer is a jazz brass player and vocalist, leads a band called Skylight and plays with the Leap of Faith Orchestra. He has a radio show Thursdays at 5 p.m. on WZBC, 90.3 FM and has been blogging about jazz since 2010.

Steve Provizer has written a great article about a great artist who was also a complex human being. Provizer makes revelations about Baker that I never considered or maybe I did but I didn’t want to think about them. Being a child of the 1950’s (I was born in 1942) and discovering Chet Baker playing in the Gerry Mulligan Quartet, I didn’t think about masculine or feminine in terms of the artists I followed. Chet’s playing was a cool breeze that cleared the smoke away. When I began to listen to his singing it was unique, surprising, tender, and lovely. Thank you, Provizer, for your writing talent.

I was just listening to Chet now and was curious if he was gay or he just sounded sensible and honest as you said. I googled “was Chet Baker gay” and I found this article. I loved every word. Honestly! It’s SO well written, so interesting and dynamic, and all the fancy words fall beautifully into place!

Such a wonderful musician Baker was, I guess now we are more appreciative of his wonderful talent! Thank you for this amazing post 🙂

Thank you to Octavio and belated thanks to Phillip. I’m very glad you found your way to this piece and got something out of it.

Yes, this commentary was so interesting to read for someone new to listening to jazz and this artist in particular. It was insightful and helpful to me on many levels.. Appreciate it, Carolyn

I’ve always listened to jazz. My mom is a huge fan of Sinatra and I’ve always had a love for Dean Martin my self. However, the other day as I was listening to pandora, I discovered Chet Baker and immediately fell in love. Thanks to this article, I feel a little closer to knowing the man behind the lovely voice. Thank you.

Thank you for reading and for your comment.

Hi Steve,

Great article on Baker’s singing. You do an excellent job of explaining what made Baker’s vocal style so different from other singers. I’d say that Baker was not a technically great vocalist, but he was someone who was able to get the emotion of the song across-he was a very effective singer. I really like the album Embraceable You, which features a lot of Chet’s vocals-it was recorded in 1957, but not released until 1995. I also like the Italian-language vocals Baker did that show up as bonus tracks on Chet is Back. In particular, I like the song “So Che Ti Perdero,” which shows how high his range was.

Because I really like it, and because it’s unique, I’ve always been fascinated by Baker’s vocal style. I hear his influence in Joao and Astrid Gilberto’s vocals in the early 60’s. Listening to Baker this morning I was struck by the smokey, foggy quality of his vocals – like a smokey jazz sax, I also hear Mel Torme’. There’s nothing “crisp” about this guys singing and I love it.

The crooner era was the first salvo fired against manliness in pop music. (I mean the prevailing mode of manliness. A manly-man answers the call of his time.)

Some early crooners such as Jack Fulton or Will Osborne were tenors or even full on falsetti – hard to imagine their appeal to women even in the 20s. In fact Osborne became an excellent bass-baritone once Crosby opened up the lower range for exploration.

With Baker, real jazz had to come to terms with pop vocal romanticism that the crooner era had caused to flourish. This was new, and perhaps the pushback can be understood. Modernism was anti-romantic and male sexuality followed suit. The bop players were swaggering doers – the commercial cats, solid providers. Then there was Chet, confounding all that.

Well Said! Thank you!

OMG!!!! Finally, someone has paid Chet Baker the tribute he deserves!!! I grew up in NYC in the 50’s when Monk, Coltrane and Mingus were regulars at the Five Spot. I was an east coast jazz snob until I heard Gerry Mulligan and Chet Baker, and of course Stan Getz, Lennie Tristano, Lee Konitz, and Dave Brubeck! I too am a product of the 40’s , I loved Chet’s trumpet from the first time I heard it and I always loved his voice. His later life was tragic but I never gave up on him. I put him in my “trunk” of favorites which included Miles and Bird and Monk and Mingus and Brownie many others. The only one I never saw in person in the City was Bird. He died before I could legally go into a club. There were incredible clubs then: The Five Spot, Half Note, the Village Vanguard, Birdland, and Basin Street downtown; and Minton’s and Smalls in Harlem. I saw Mulligan in New York but never had the pleasure of seeing Chet in person.

Thank you Steve!!!! The article is brilliant!

Thanks, Trish. I appreciate your comments.