Book Review: Astaire, Balanchine, and Kelly — The Foundations of Film Dance

While Beth Genné proffers a terrific take on dance and its social context, she exhibits a shaky grasp of musical-theater history.

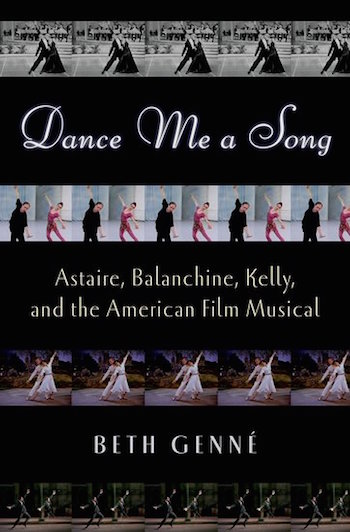

Dance Me a Song: Astaire, Balanchine, Kelly, and the American Film Musical by Beth Genné, Oxford University Press, 376 pages, $35.

By Christopher Caggiano

In the pantheon of classic Hollywood musical choreographers, a couple of deities stand out: Fred Astaire and Gene Kelly. In her new book, Dance Me a Song, author Beth Genné argues that we should add George Balanchine to that short list.

In the pantheon of classic Hollywood musical choreographers, a couple of deities stand out: Fred Astaire and Gene Kelly. In her new book, Dance Me a Song, author Beth Genné argues that we should add George Balanchine to that short list.

Um…George Balanchine? Sure, Balanchine is virtually synonymous with classical dance in the 20th century, and had a fairly significant impact on Broadway dance as well.

But Hollywood? Balanchine only made a handful of films in the late ’30s and early ’40s: The Goldwyn Follies, 1938; On Your Toes, 1939; I Was an Adventuress, 1940; Star Spangled Rhythm, 1942; and Follow the Boys, 1944. None of these films is especially memorable, though they contain some scintillating dance sequences, most of them featuring the luminous Vera Zorina, Balanchine’s then wife.

Genné sets out to demonstrate that Balanchine did more than just inspire Astaire and Kelly. He influenced film choreography in general. The author also discusses the various people who worked with these men — directors, orchestrators, lighting designers, and cinematographers — with the aim of exploring film choreography as a uniquely collaborative art. She also makes the case for the serious discussion and analysis of film dance, hoping to bring respect to an under-appreciated art form.

A worthy goal, to be sure. But Genné and I are in fundamental disagreement regarding the artistic quality of most Hollywood musicals. Even the best movie musicals (those that were written as films, not film adaptations of Broadway musicals) tend to be fairly disjointed affairs, with songs cobbled together from previous films and stage shows. Dance numbers often have tenuous connections to the story. The only truly great Hollywood musicals began as great Broadway musicals, West Side Story, My Fair Lady, and The Music Man among them.

Even the supposed gold standard of Hollywood musicals (Singing in the Rain, An American in Paris, The Band Wagon) feature previously existing songs, sometimes alongside new material that, like the interpolations, hasn’t been particularly well integrated into the story. What’s more, Hollywood musicals frequently feature the lazy device of a show-within-a-show, which relieves the creators of the necessity of even trying to make the songs contextual. What’s more, those shows-within-shows are usually revues, which requires even less thought regarding story/song/dance integration.

In order to make her argument, Genné consistently overstates her case regarding the dramatic impact of the dances she analyzes. She claims that “as choreographers and dancers, Kelly, Balanchine, and Astaire aimed to use dance as a vehicle for the development of a character or plot within the context of an overall film narrative.”

I suppose “aimed” is the operative word here, because it’s hard to look at something like the Romeo and Juliet ballet in The Goldwyn Follies (1938), “The Limelight Blues” from Ziegfeld Follies (1946), or “Be a Clown” from The Pirate (1948) and think of the dance as being dramatically meaningful in a larger context. Ziegfeld Follies is a revue. There’s no plot to contribute to. In The Pirate, the famed and glorious Nicholas Brothers suddenly show up for no particular reason and start dancing with Gene Kelly as his character literally dances for his life, while incongruously singing about the joys of clownhood.

(Also, in her extended discussion of “Limelight Blues,” Genné makes no mention of the fact that Fred Astaire is wearing yellow-face makeup, nor that his playing an Asian character is an act of cultural appropriation. These are rather odd omissions in a book published in our current ‘woke’ environment. To her credit, Genné goes to great lengths to establish the African American roots of film dance as well as dance in general.)

When discussing the psychological depth of the dances that Astaire, Kelly, and Balanchine created, Genné also overstates her case. She posits that their film ballets “explored the complex and conflicted feelings that lurk beneath the conscious thought in that dream world that so fascinates psychoanalysts in the 1940s and ‘50s.”

In truth, these film ballets are nowhere near as psychologically rich and complex as the stage ballets of Agnes de Mille, particularly those in Oklahoma! and Carousel. Genné dismissively refers to De Mille as being “rather late on the scene.” This is a tremendous disservice to a pioneering choreographer who created the mature and sophisticated dream ballet as we know it.

Balanchine’s ballets for the stage show On Your Toes, which were the only numbers retained for the 1939 film version, are (at best) prototypes for De Mille’s seminal stage work. The “Princess Zenobia” and “Slaughter on Tenth Avenue” ballets can only be considered integrated in the sense that the main character is a dancer performing in the ballets. Their narratives have nothing at all to do with the larger narrative. The ballets in Oklahoma! and Carousel are central to the story of each show, and add layers of complexity to their narratives.

Credit where it’s due, Genné, a professor of dance at the University of Michigan, exhibits an authoritative grasp of the larger trends in the dance world surrounding these men, as well as the social and cultural context in which they worked. She describes Kelly and Astaire as having “poeticized the everyday movement, casual posture, gestural language, and sports moves of the young Americans who came of age after World War I.” She also makes numerous pithy and apt observations, for instance when, in analyzing Astaire’s “outlaw” style, she describes the dancer as making “an art form of slouching.”

Genné is at her best when recounting the fascinating biographical and vocational connections between Astaire, Balanchine, and Kelly. It was particularly captivating to read about Astaire’s collaborations with Gershwin, and how Astaire made musical suggestions to the composer, while Gershwin suggested dance steps to the dancer. Likewise fascinating was the relationship between Balanchine and composer Vernon Duke, both Russian expatriates.

Fred Astaire and Gene Kelly in “The Ziegfeld Follies.”

However, once Genné arrives at describing the dances themselves, the book becomes a slog. She clearly sees a benefit in cataloguing the minutia of the dances, as well as the camera angles and lighting effects that add to their impact. But all the detail makes for pretty dull reading.

While Genné has a terrific take on dance and its social context, she exhibits a shaky grasp of musical-theater history. She refers to the songs of musicals from the ’20s and ‘30s as “mostly written…specifically for the dancers—the character they played and the dances they developed.” Actually, at that point in musical-theater history, songs were written to be hits. They often had little to do with the show’s plot, or were generic to the point where they could easily be used in a different show entirely. That’s why we get songbook shows like Nice Work if you Can Get It and Crazy For You. Integrated scores didn’t really take hold until Oklahoma! (1943) and beyond. (Genné also twice refers to the landmark musical Show Boat using the solecistic Showboat.)

Dance Me a Song serves up fascinating insights about the effects these men had on each other, as well as the larger world of film dance. And it is tremendously valuable when it documents the dances of Astaire, Balanchine, and Kelly. If only Genné’s prose had done a better job of describing the scintillating nature of their accomplishments.

Christopher Caggiano is a writer and teacher based in Boston. He serves as Associate Professor of Theater at the Boston Conservatory at Berklee. His writing has appeared in American Theatre and Dramatics magazines, and on TheaterMania.com and ZEALnyc.com.

Tagged: Balanchine, Beth Genné, Christopher Caggiano, Dance Me a Song, Fred Astaire, Gene Kelly, and the American Film Musical