Book Review: “Another Life” — Curing Writer’s Block

This slender memoir reads like a rambling conversation with a literary stranger you meet on a train.

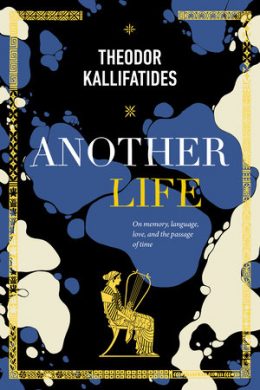

Another Life: On Memory, Language, Love, and the Passage of Time by Theodor Kallifatides. Translated from the Swedish by Marlaine Delargy. Other Press, 131 pages, $29.95.

By Helen Epstein

Writers should stop writing after the age of seventy-five, an editor of a Swedish cultural magazine says casually to Theodor Kallifatides as they are enjoying drinks in Stockholm. “It’s okay until seventy-five, but then something happens to them.”

Kallifatides, who is 77 and seems depressed, does not question the editor’s manners or motivations. Instead, he wonders if that “something” is happening to him: “Was it still possible for me to organize my days around a text?” A Greek born in 1938 and living in Sweden since 1964, Kallifatides has published more than 40 books of fiction, non-fiction, and poetry. He has translated Strindberg into Greek and Theodorakis into Swedish. He has a faithful publisher. Yet he decides to sell the studio where he has worked without interruption for decades: for the first time in his life, he is unable to write.

Another Life begins promisingly enough with a description of how, for decades, the author had observed and eavesdropped on his characters with endless interest:

That was how my days had passed ever since 1969, when my first novel was published. No writer’s block. No interruptions to the flow. Every book was a bridge to the next. Almost like love affairs. But now it was 2015 and my strength was dwindling….I might be able to write about why I couldn’t write, but it wasn’t a pressing need. It would be better to stop.

In this book, the author evinces little, let alone “endless interest,” in his characters. His wife is a walk-on character; his children are absent; his friends are neither described or characterized in any depth. Kallifatides’ ennui about writing is compounded by his distaste for the contemporary life he witnesses:

It was agonizing to see Sweden changing, step by step. Social justice and solidarity were giving way to the visible and invisible power of the market. Education was becoming increasingly privatized, as was care. Teachers and doctors were turning into entrepreneurs, students and patients were becoming clients. It was all happening so fast that it didn’t even have time to register as history. The pay gap was growing year by year. Greed was in the driver’s seat, the boundless freedom of the individual was now the guiding star.

He sells his beloved studio without describing why, exactly, he decides to, and retreats into the home he has shared with his wife of 42 years, who seems to be aging more gracefully and making the adjustment to retirement with far less difficulty. He contemplates still being an outsider in Sweden at a time when immigrants are demonized and his homeland, Greece, is shamed in the European community. He begins to sketch portraits of immigrants in his neighborhood and friends who have died, which eventually lead him back to the village where he was born and to the language of his childhood.

Author Theodor Kallifatides — his books have reportedly been translated into some 20 languages. Photo: ekathimerini-com.

The slender memoir that Kallifatides wound up writing reads like a rambling conversation with a literary stranger you meet on a train. It’s all intelligent and more or less diverting but there is little continuity in his stories and you soon lose track of both where he started and where he seems to be going. He has a disarming way of sprinkling one-liners into his narrative (“In Greece they dreamed of the Swedish model, while in Sweden they dreamed of the Greek lack of any model”) and an outsider’s curiosity about the linguistic quirks of Swedish. But he has an annoying habit of digressing into what appear to be the weeds to a reader unfamiliar with his work. Though his books have reportedly been translated into some 20 languages, they have not been published in the United States. I found myself wondering why Other Press hadn’t published the author’s autobiography or the best of his novels rather than this meandering and superficial set of musings on writer’s block, contemporary immigration, his family members, death, food, and the consequences of intolerance and societal breakdown throughout Europe.

By the end of Another Life — I will not spoil the only real event in the book by describing how it develops — Theodor Kallifatides is writing again. The cure to his malady involves a return to Greece. I assume that his devoted readers found it moving and meaningful. I wished I could have found this book as insightful as the cover copy advertised, but thought this slight memoir lacking both weight and complexity. Since Kallifatides is considered one of Sweden’s most significant writers, I hope that Other Press will consider publishing one of his more significant books.

Helen Epstein has reviewed for The Arts Fuse since 2010. She is the author of ten books of non-fiction including the recent The Long Half-Lives of Love and Trauma (available from Plunkett Lake Press), just published in Czech.

Tagged: Another Life, Culture Vulture, Other Press, memoir, nonfiction

Thanks for another reason why depressed journal entries should not find their way to publication. And what an ass that editor was! It’s restorative to think of the legion of writers who didn’t miss a beat at 75… John Berger, Jean D’Ormesson, the poet Friederike Mayroecker… Who will continue the list?