Jazz Commentary: Response to “The Jazz Bubble”

Arts Fuse Jazz critic Steve Provizer responds to Dale Chapman’s book The Jazz Bubble: Neoclassical Jazz in a Neoliberal Culture.

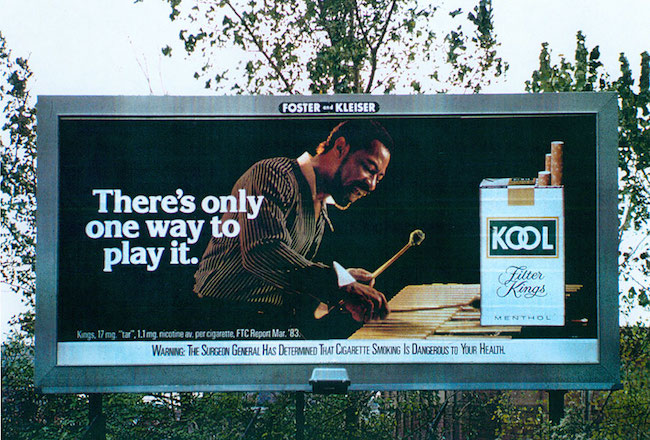

Ad for Kool cigarettes, circa ’60s – ’80s

By Steve Provizer

There are aspects of the argument in The Jazz Bubble that ring true to me. [See interview with author Dale Chapman in The Arts Fuse.] There’s been a massive redistribution of wealth and a commensurate shredding of labor unions and the middle class. The acceptance of “increasing shareholder value” has definitely come to dominate business language, including in arts and culture. But there’s a lack of valuable historical perspective in The Jazz Bubble and an exclusion of the thoughts of a range of jazz musicians that undercuts Chapman’s neat calculus about the relationship between business and jazz.

Chapman’s thesis is that the investment of neoliberal economic/business interests in jazz became qualitatively different in the ’80s, and that this is reflected in the ascension of the “neoclassical” jazz of Wynton Marsalis and the “Young Lions.” Chapman’s thesis might have become more convincing to me if he had chosen to bring in more perspective on the history of the relationship between business and the art of jazz. As far as I’m concerned, business involvement has always been self-interested and to some degree, necessary. It also carries with it occasional positive side effects for artists and local communities.

One way or another, you need metrics to pay artists. In jazz, metrics were once ticket sales, drink receipts in clubs and record sales. I imagine that what fiscal health that jazz enjoyed in the first part of the 20th century was because those metrics were solid. No more. Round about the ’60s, those metrics began to slip, and corporations began subsidizing jazz festivals. Playboy sponsored a jazz festival as early as 1959. Actually, “From Spirituals to Swing,” the famous 1938 and 1939 concerts in Carnegie Hall, were sponsored by The New Masses, the magazine of the Communist Party. Cigarettes makers, beer brewers, banks — any number of organizations or corporations with their own ‘branding’ agendas have been sponsoring jazz for many decades. I have a picture on my wall of Harry James flogging Chesterfield cigarettes in the ’40s. Yes, white musicians picked up more and better endorsements than black ones, but there have always been ample examples in the black media of jazz stars being used to sell product.

So, pinpointing when the “disruptive innovation” posed by jazz became co-optable by the world of business is not all that simple. Chapman believes the jazz of the ’80s marks a watershed. Why then, rather than an earlier period? Yes, there was a conservative aspect to the clothing style and in the language that emerged with Wynton Marsalis and the Young Lions of the ’80s. What Marsalis has said remains divisive. But the weight Chapman gives to this conservatism is mitigated when you realize that Miles Davis, to whom Chapman unfavorably compares Marsalis and company, was an important element in several retail clothing campaigns. He was a notably conservative, Ivy League-style dresser until the late ’60s.

And yes, nostalgia was at work with the apotheosis of saxophonist Dexter Gordon when he returned to the U.S. in the late ’70s and early ’80s. That nostalgia no doubt made for a convenient foothold for institutions looking for ways to expand their footprints in certain communities. But, the targeting of markets has always been based on leveraging demographics — us versus them — and this categorization usually amounts to the cool versus the not-cool. And speaking of cool, Kool cigarettes had billboards in pretty much every black community in America from the ’60s-’80s. (see ad above). How much difference is there between using the music to sell the fantasies in these ads or using it to sell nostalgia?

I am not sure Chapman hasn’t played fast and loose with Gordon. On the one hand, he extols the musician’s playing and talks about how authentic it is in light of African-American experience. On the other, he says that Gordon also somehow allowed himself to become a useful tool, an example of “heteronormative” masculinity; this somehow made the world safer for neoliberal capitalism. Geez, the guy can’t do anything right. Ditto Joe Henderson who, despite his great playing, was marketed as a tool in Verve Records’ neoconservative strategy. Gordon and Henderson are treated like points in an argument, rather than as individual, self-aware musicians.

Chapman makes much of the degree to which the concept of self-responsibility was elevated by both the Young Lions and the business world. And he compares Wynton Marsalis rigidly defining the “acceptable parameters” of jazz to “the market’s invisible hand.” That comparison is tricky, because jazz has traditionally been a meritocracy. Either you cut it on the bandstand or you didn’t. At least, this code has traditionally been at play in the mainstream, commercially viable stream of jazz. Other kinds of jazz, while possibly less cutthroat, generated very little income for the musicians.

Similarly, were institutions and “market processes” really held more responsible for the financial failings of individuals in earlier days, as Chapman observes? I don’t recall those days. Groups and individuals — not institutions and market processes — have always taken the brunt of blame for a given musician’s inability to deal with risk and take control of their own finances.

Here are a few other points:

The “Jazz Bubble” has a narrow meaning. It sounds catchy, but it has little relevance thematically. It simply refers to the fact that when one kind of jazz seems to catch a buzz and sell well, record companies want to jump on the bandwagon and produce what in the film industry would be termed endless sequels. This may have been a more pervasive phenomenon in the ’80s to ’00s, but it’s hardly unique to that time period.

Ella Fitzgerald a “quintessential bebop artist”? She picked up some bop, but was a quintessential swing artist.

As for the veiled or less-then- veiled sexual innuendos about disco launched by the jazz establishment in the ’70s — jazz has always had issues with gender and sexuality.

In this book, Chapman gives us a boatload of interesting data. The fact that so many business consultants and publications have taken concepts from jazz and translated them into the business domain is starting, to say the least. It’s a little unsettling for a jazz person to read about “performative flexibility, being alive to the potential of the moment as useful business tools.” Then there’s the analogy of jazz to the “entrepreneurial self, set loose within the conditions of the free market” and “…that jazz musicians provide a space in which risk taking can generate new and innovative ideas.” Let me note that, although laden with acronyms and various kinds of jargon, the book is written clearly and quite readable. Also, any tome about jazz by an academic with no mention of Adorno is ok in my book.

Chapman is obviously thoughtful and widely-read and I can’t help but feel that he has omitted some historical perspective in order to nail his thesis about late 20th century neoclassical jazz and neoliberal culture to the jazz club wall. Some of this perspective could have come from hearing the voices of a wider cross-section of jazz musicians, including those who may or may not have been trapped in ‘The Jazz Bubble.’

Jazz Bubble author Dale Chapman responds to Provizer’s criticism here on The Arts Fuse.

Steve Provizer is a jazz brass player and vocalist, leads a band called Skylight and plays with the Leap of Faith Orchestra. He has a radio show Thursdays at 5 p.m. on WZBC, 90.3 FM and has been blogging about jazz since 2010.