Television Review: Elvis Presley — The Searcher?

What we don’t learn very much about is Elvis’ inner life, his motivations, and his deeper ambitions.

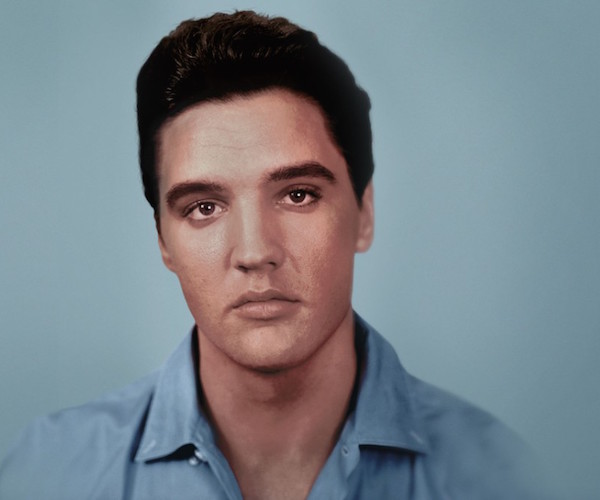

“Elvis Presley: The Searcher” Photo: HBO.

By Matt Hanson

The first awkward thing about HBO’s documentary Elvis Presley: The Searcher is its title. Elvis was, of course, was an immensely mythic American phenomenon whose subsequent biographies are often given deservedly grand, poetic titles, like Peter Guralnick’s companion volumes Last Train to Memphis and Careless Love. Let’s not even get into the neon-lit titles of his filmography: Jailhouse Rock, Blue Hawaii, Viva Las Vegas, etc. Calling him a “searcher” doesn’t really say very much about the man himself (searching for what, exactly? Or for whom?) but conjures up images of an alternate universe where Elvis finally gets a serious dramatic role and turns into a vengeful cowboy after marauding Comanches raid his homestead and kidnap his daughter, causing him to spend years wandering in the bad lands outside civilization, obsessively bent on bloody revenge.

In some ways, there isn’t any urgent need for a non-fiction study of Elvis (in what must be a publicity nightmare, another documentary on the King has been released this year — check out The Arts Fuse review). But, then again, you can’t be too sure about these things. Remember that anyone who was born at the turn of the current century has only now begun to hit voting age, so there’s no telling what anybody under the age of, say, thirty knows about any of the pop heroes of yore. When a friend of mine told her sophomore college class about Bob Dylan winning the Nobel Prize, there was a general murmur of acknowledgement but one student (who was probably the only one willing to admit it) asked, in all earnestness, “who’s Bob Dylan?”

There are plenty of interesting and useful ways to talk about the life of Elvis Presley, but director Thom Zimmy doesn’t seem to know exactly which one he wants to focus on. So much of his story has been handed down to us already, with all its Capra-esque qualities intact: the rise from literal rags to obscene riches fueled by his magnificent talent, the Dionysian stage presence, his being a nice Southern white boy who both adored and profited from black music, the complicated family life and devotion to his mother, his prolonged public overdose on fame and wealth. The main problem with The Searcher is that it presents each of these topics, it doesn’t investigate them in depth.

The film does contain a great deal of historic film footage of Elvis, both onstage and off. One of the things that made Elvis compelling wasn’t just his great set of pipes but his sly, almost feline physical presence. Elvis’ seductive appeal to so many people can partly be credited to his incredible gracefulness, an uncommon ease in his own skin, his bashful mama’s boy smile glinting under his crown-like black pompadour. We see how infinitely marketable Elvis was to the millions of repressed teenagers who would eventually become the counterculture — he was a raucous Rhythm and Blues singer you could bring home to meet your parents. Figuring out who the person underneath the rhinestones really was is part of the biographer’s job, but The Searcher doesn’t make more than superficial forays into understanding its subject’s inner life.

One of the major issues surrounding Elvis as a musical phenomenon, as well as a historical one, is his complex relationship to race. We know that part of what made Elvis a superstar is that Sam Philips, the blues-loving proprietor of Sun Records, needed someone who could bring the earthy vibe of segregated “race” records to a wider (which is to say, white) audience. This puts our hero in an interesting, complex position to the music he performed — is he an appropriator, essentially a musical colonizer, of black culture or the ultimate devotee, an ideal ambassador for black music? The film doesn’t do more than provide a few cursory glances at the topic, which is odd, especially given the film’s epic length.

For one thing, the rumor persists that Elvis was a racist, and some pretty vile things have been incorrectly attributed to him for some time. Setting this thorny part of the record straight would have been an excellent thing for a documentary like this to do. But Zimmy gingerly tiptoes around the topic, which is a real disappointment, because Elvis was indeed a product of his place and time. But, based on solid evidence, he wasn’t guilty of the racism, casual or otherwise, he has been accused of. In fact, there doesn’t seem to be very much commentary in the film by any people of color at all. Instead, we hear Tom Petty and Bruce Springsteen eloquently and authoritatively explain how amazing Elvis’ music was. But we knew that already. And if we didn’t, there’s plenty of clips to prove it.

What we don’t learn very much about is Elvis’ inner life, his motivations, and his deeper ambitions. It’s clear that Colonel Tom Parker and his Memphis Mafia were determined to milk every last golden drop out of their cash cow — virtually every aspect of their subject’s life and career was tightly controlled. Elvis seemed too passive and/or intimidated by Parker’s gruff presence to speak up for himself. This means that the power of his larger ambitions — to focus on gospel music (his first musical love) and take on more dramatic roles — remain fuzzy. If only Zimmy had been able to tell us more about them. Parker had him cranking out film after kitschy film long after the novelty wore off for its exhausted star, who had very little to say about his frustrations in public. In one interview it’s clear he is bored with his pin up status: he wants to try something new, more from the heart. But the film doesn’t really explore Elvis’ dreams, or the tantalizing possibilities of what they might have actually looked like in reality.

By the time Elvis started his Vegas residency, the writing was on the wall. Again, his slightly pathetic inability to stand up to Parker’s grueling concert schedule made him more of a victim than he ought to have been. The uppers he took for breakfast and the downers that helped him sleep, also due to Parker’s pressure, put him in a constant daze. One of the film’s few inspired visuals is a superimposition: a picture of a tiny and helpless Elvis, curled in the fetal position, slowly floats above the bright lights of Vegas as fireworks pop all around him. It’s an evocative visual effect, and one of the film’s frustratingly few attempts to dig into its subject’s emotional states.

Did the soft-spoken, rather sheltered Elvis really have much of an inner life? Apart from the superficial trappings of mega-stardom, and all the glitzy performances, I tend to think that he did. His singing, especially when he digs deep into the gospel tunes he grew up on, suggests a sense of something deeper existing beyond his considerable showmanship. Examining the documentary’s photographs and footage, it’s easy to see how the look on his famous face changes gradually — from lean, confident, and bemused when young to sagging, world-weary, and almost fatalistic with the approach of middle age. But, again, it’s Elvis’ exterior that’s left to suggest whatever emotions are locked away inside.

America tends to be brutally Oedipal with its pop stars (and politicians) — we build them up to unmanageable heights of fame and fortune only to gleefully tear them down. Maybe this happens because as much as we bask in the extraordinariness of certain people, their exceptional qualities are precisely what makes the masses feel inadequate in comparison. Amid all this toxic psychological projection, we don’t often bother to consider what the objects of our collective desire actually think or feel. We willfully forget what makes them all-too-human. The story of Elvis is one of the clearest examples of this process at deconstruction — it’s a shame that The Searcher doesn’t search hard enough find the man behind the image.

Matt Hanson is a critic for The Arts Fuse living outside Boston. His writing has appeared in The Millions, 3QuarksDaily, and Flak Magazine (RIP), where he was a staff writer. He blogs about movies and culture for LoveMoneyClothes. His poetry chapbook was published by Rhinologic Press.

Tagged: Elvis Presley: The Searcher, HBO, Matt Hanson, documentary