Jazz CD Review: Coltrane’s “Lost Album” — Not the Holy Grail

You might argue that this session was forgotten, but this new release shouldn’t be thought of as lost — because no one was looking for it

John Coltrane, Both Directions at Once: The Lost Album (Impulse)

By Michael Ullman

Already dubbed “the holy grail of jazz” by publicists with a shaky grasp of theology, Both Directions at Once: The Lost Album is a two-disc set of music recorded by the John Coltrane Quartet with McCoy Tyner, Jimmy Garrison, and Elvin Jones on March 6, 1963. It was then (mostly) put away by producer Bob Thiele. One number, the fifth take of “Vilia,” was issued on the third of a valuable series of recordings from Impulse called The Definitive Jazz Scene. The track has been reissued since. The rest of the music on Both Directions at Once is being made available for the first time. Some of it was repressed for obvious musical reasons; the rest perhaps because the recording date was elbowed aside by the dozens of other Coltrane sessions recorded by Impulse. (Coltrane made what I consider to be a masterpiece, John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman, the day after this Lost Album session.)

You might argue that this session was forgotten, but this new release shouldn’t be thought of as lost — because no one was looking for it. In truth, it’s lucky the material on Both Directions at Once survived at all. Impulse’s original tapes, we learn in the album’s notes, were the victims of numerous purges by ABC Paramount. These two discs are copies of the session that Coltrane, and then his family, retained privately. The sound is mono, but it is sharp and clear and well balanced.

The music found here is more than welcome, even to this listener, who has close to ninety discs led by Coltrane. But it is also, despite the hype, variable in quality. What we have of the session begins with take one of what is entitled Untitled Original 11383. The performance — if not the minimal tune itself — is problematic. Coltrane solos first on this exercise in the blues, playing the theme twice before beginning his solo, which doesn’t seem to end so much as peter out. This makes for an awkward transition to McCoy Tyner’s solo, like a botched handoff in a relay race. Nor does Tyner sound particularly energized once he is finally handed the baton. A bowed solo by Jimmy Garrison ensues and, to my ears, this is the highlight of the track, even though Elvin Jones seems surprised when Garrison switches to plucking the bass. Coltrane comes back in and he sounds more engaged, but the band appears to be still warming up.

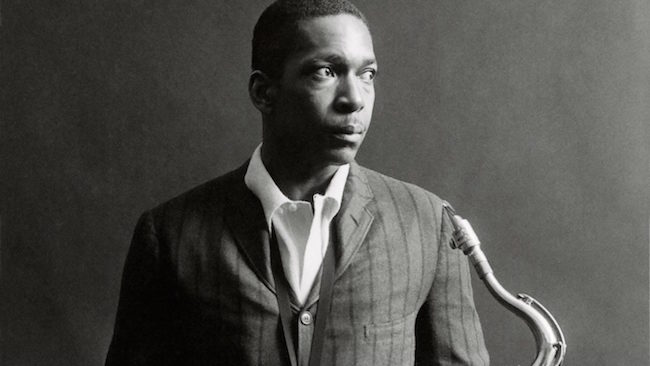

John Coltrane — tried to achieve perfection by indulging in multiple takes

I don’t know what to make of the lethargic version of “Nature Boy” that follows. It begins with a kind of fade in, Garrison playing a repeated figure over Jones. Coltrane states a restrained version of the melody and then improvises for a bit — he drifts out. The entire track lasts three and a half minutes; I am sure Coltrane wouldn’t have issued it himself. He would re-record the tune two years later. What comes next is much more satisfying: the first take of Untitled Original 11386, a zesty tune and performance. Side two has two more versions of this piece: take five is remarkable because this time around the rhythm section comes together seamlessly. Jones sounds as if he is having a lot of fun; Coltrane is impassioned. The second disc also contains the previously issued recording of the delightful “Vilia,” notable for Coltrane’s sprightly lyricism and Tyner’s briskly melodic solo.

Coltrane was advised by Duke Ellington to refrain from trying to achieve perfection by indulging in multiple takes. The saxophonist had trouble following that advice. We have four takes here of “Impressions,” based on the two chords of “So What.” I welcome the alternates, but I continue to believe that the best recordings of this number, which Coltrane played often, are on his various live sessions. A highlight of this set, and it would be a gem on any jazz album, is the twelve minute “Slow Blues.” Coltrane had already proved himself to be a master of this genre. On his first album as a leader for Prestige Coltrane recorded “Trane’s Slo Blues” and “Slowtrane.” His Coltrane Plays the Blues is one of his greatest Atlantic albums. Here he stretches out, adroitly exploiting his unique tone and strategies — neatly truncated series of short phrases, tortured sounding wails, half-stated notes generated by false fingering, barks, swirls, and, at times, resolutely straightforward long tones. And Tyner’s solo is equally satisfying. So, the music on these two discs may be uneven and provide no revelations, but Both Directions at Once contains some tracks that many of us will want to hear again and again.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for The Atlantic Monthly, The New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, The Boston Phoenix, The Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.)