Jazz CD Review: Buster Williams — An Exemplary Modern Bassist

There are no missteps on this disc. Buster Williams and company make all the complications swing, mightily.

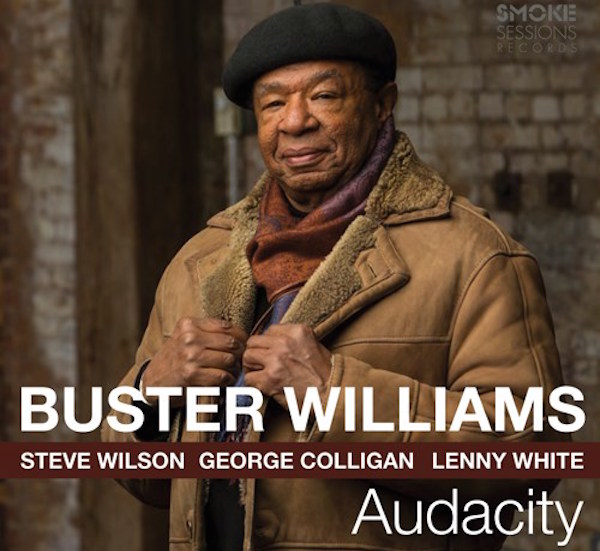

Audacity, Buster Williams. (Smoke Sessions Records)

By Michael Ullman

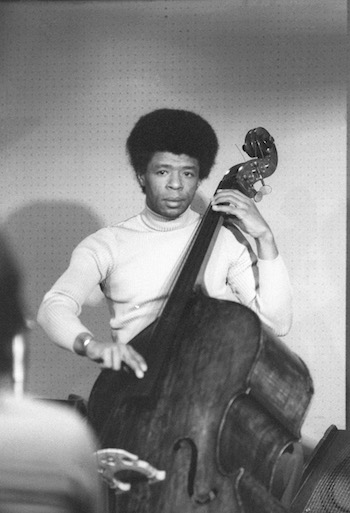

The first notes we hear on Herbie Hancock’s The Prisoner, dedicated to Martin Luther King, emanate from the warm bass of Buster Williams. He would go on to make five more albums with Hancock, including the seminal Mwandishi. His fleet flurries of notes, singing phrases, glissandi, and funk patterns stand as a powerful counterpoint to Hancock’s concentration on melody in Mwandishi‘s spacey, lyrical ballad “You’ll Know When You Get There.” Hancock seemed to write with Williams’ varied musical strengths in mind. His bowed bass is a crucial part of the ensemble on the track “Wandering Spirit Song.” Later on in the album he doubles on the melody and fills open spots with his big-toned lines. Williams is the exemplary modern bassist — he has recorded prominently, often playing a chameleonic role in different ensembles.

Williams was already well known, and widely experienced, in 1969 when he made Mwandishi. His father was a bassist from New Jersey, who, the story goes, was asked to fill in at a 1960 date with the Sonny Stitt-Gene Ammons band. Dad sent Buster instead, and Stitt hired the teenager to go on the road. Williams early recordings include a string of sessions with singer Nancy Wilson, but he seems to have played with everyone and in every genre. He probably met Hancock while subbing with Miles Davis. He made a series of LPs with Dexter Gordon. Williams is on Stan Getz’s The Peacocks, Lee Konitz’s Yes, Yes Nonet, McCoy Tyner’s Asante, The Betty Carter Album, Woody Shaw’s The Moontrane, and Hamiet Bluiett’s Dangerously Suite. (I am picking my favorite albums from Williams’ voluminous discography.) In the late ’70s bassist Ron Carter paid Williams the ultimate compliment: he hired him as the bassist in a band that featured Carter himself on piccolo bass.

Bassist Buster Williams circa 1980. Photo: Michael Ullman.

Williams has also made over a dozen LPs as a leader. His new album of originals, Audacity, features saxophonist Steve Wilson, pianist George Colligan, and drummer Lenny White. The band, according to Colligan, has worked together off and on for fifteen years. They prepared for this recording with three nights at the New York night club Smoke. The results prove that they were ready.

The six Williams originals (with three penned by band members) are challenging in different ways. Like many of Hancock’s best creations, Williams’ compositions eagerly shift moods and rhythms. Audacity begins with a straightforwardly swinging piece, “Where Giants Dwell,” though the tune is intriguingly complicated, from its extended melody to some unexpected changes. Williams dedicates “Song of the Outcasts” to the “gypsies of the world” — meaning the travelling musicians around the globe. The song starts off with a dark, out-of-tempo piano solo whose tremolos are meant to suggest flamenco. Then Colligan plays a vamp while Wilson states a somber melody that seems to evaporate in order to introduce another piano solo, except this time around Lenny White enters with a chattering pattern on snares. The improvisations are presented over this new tempo, and a rhythm that Colligan identifies for us as 13/4.

“Ariana” is a slow piece that, after a pokey introduction, turns into a pensive waltz, whereas the title cut is a ripping mid-tempo composition starring an extended solo by Williams. The bassist doesn’t dominate the album: he’s a consummate ensemble player. Wilson and Colligan are inventive, adept soloists. The compositions are complex, the band is tight and disciplined as well as inventive. There are no missteps here. Williams and company make all the complications swing, mightily.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for The Atlantic Monthly, The New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, The Boston Phoenix, The Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.)

Tagged: Audacity, Buster Williams, George Colligan, Lenny White, Smoke Sessions Records