Book Review: Herman Melville and the Solace of Movement

“Life, you see, is a lonely business . . . When there is a storm, it’s best to turn into the teeth of it. Don’t fly away, allowing an evil wind to come upon you from the stern. That’s our weakest part. We’re rib cage and metal up front. The bow is always best. Head into the blast, son. Into the blast.” Jack Chase to Herman Melville, The Passages of H. M.

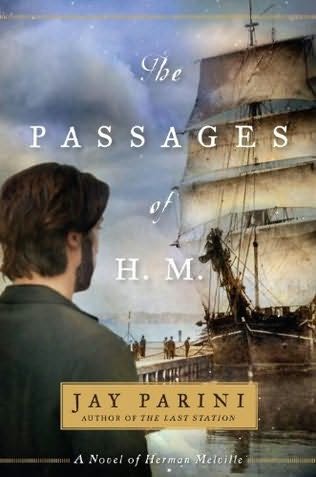

The Passages of H. M.: A Novel of Herman Melville by Jay Parini. Doubleday, 454 pages, $26.95.

By Christopher Ohge

The Arts Fuse interview with author Jay Parini

British critic F. R. Leavis once told the eminently sane novelist Arnold Bennett that he was a decent writer but that he seemed “never to have been disturbed enough by life to come anywhere near greatness.” Not so for Herman Melville: the 1852 headline for an excoriating review of Melville’s follow-up volume to Moby-Dick was “Herman Melville Crazy.” In his fine novel The Passages of H. M., Jay Parini uses fiction to explore how the disturbances of critics, as well as God’s silence, social mores, domestic disasters, and the reading public made Melville into a bedeviled but great writer.

In a compelling narrative, Parini presents a de-mythologized Melville (H. M.), though it is a writer that many of us who love his fiction may have fancied. His Melville is a genius but tremendously flawed—an unrefined, monomaniacal, manic-depressive drunkard. Because it is fiction, the book entertains speculations and shapes experience in ways that go outside of the facts in Hershel Parker’s brilliant, two-volume biography. Thus Parini’s novel positions Melville as a tragic hero of literary endeavor who rejects a normal life in order to belong to what Melville deemed, in Wordsworthian fashion, an “aristocracy of feeling.”

Throughout the novel, H. M. asks why his bad luck seems fueled by his obsession with creating beauty and understanding the mysteries of the cosmos. After early literary success with his novels Typee and Omoo, his art leads to financial difficulty, physical and mental health problems, abusive relationships, and alienation from the literary world. The suggestion is that his misfortunes and hardships are punishments for his extraordinary sensibility.

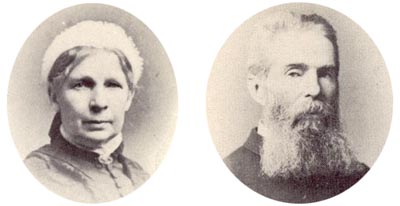

The novel flashes back and forth between different periods in Melville’s life. H. M.’s wife Lizzie give voice to his sad state after writing Moby-Dick. She is seen as a frustrated wife married to a failed, volatile writer who “sought everything or nothing, quarreling with God, accusing Him of indifference, even hatred of the human race.” Lizzie’s perspective alternates with a third person narrator who describes important events in Melville’s life, beginning with his first voyage out to sea and ending with his final voyage to Bermuda a few years before his death.

Lizzie’s personal revelations about H. M. are disturbing. Fluctuating violently in mood, prone to abusing his wife, obsessed with metaphysical subjects, surrounding himself in gloom, the middle-aged Melville is a customs house officer who prowls the docks of the Hudson by day and at night is said by his wife to have “despair coming upon him as we lay in bed, a storm blowing up in his body.”

Lizzie suggests her husband was mostly elusive with women and could only express his homoerotic feelings in his writing. Coincidentally, two men in Moby-Dick, Ishmael and Queequeg, likewise lay in bed—not in a stormy disconsolation, but in something like marital bliss (“in our hearts’ honeymoon, lay I and Queequeg—a cosy, loving pair”). Echoing Lizzie, the narrator conveys H. M.’s revelatory moment that “his life, especially his journeys, had been strangely full of elusive young men.”

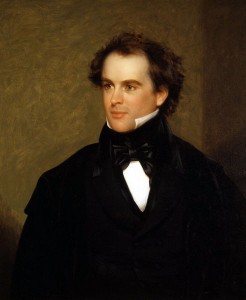

As times change so does our judgments of behavior among men. Today, some call it bromance, while in Melville’s time, after the occasion of a man-date with writer Nathaniel Hawthorne, Melville wondered about their “infinite fraternity of feeling.”

That Melville’s homoerotic tendencies made it into the novel is no surprise, yet Parini deals with this popular bookchat subject with precision. Every scene of manly love is as ambiguous as the documentary evidence suggests, and there are no sex scenes between H. M. and another man. Instead, H. M. makes moves that perhaps push at conventional boundaries, or he admires another man’s naked body. For example, here is the young H. M.’s lazy days lying with the young sailor John Troy:

The problem was that his friend had lately—at least Herman thought so—cooled to his gestures of affection. He wondered if, indeed, he had gone too far one night, letting his hand brush against Troy’s thigh, allowing it to rest there for a long time. H. M. knew that men aboard whalers often “helped” each other, touching in the most intimate ways, releasing anxieties in the way men do.

John Troy snubs the notion as unmanly and heathen.

“In the way men do” leaves us with little clarification, though we can fill in the blanks when the venerable Jack Chase (to whom H. M. dedicates Billy Budd) admits to H. M. of having “affections” with men aboard various ships. While seeking these affections, Melville may never have achieved coupling with other ‘elusive men,’ young or old. These affections lead to crushing trauma, which sparks literary creation, as is evident when John Troy separates from H. M.

. . . he fell to his knees, dipping his forehead to the grass. He could feel the long rivers of night churning through him, the tears of the world gathering and pushing against a dike that might well burst, at which point he would break apart and scatter, float in a million pieces, sucked into the blackest void ever imagined. He might never again assemble in the hirsute, ungainly sack of skin known as Herman Melville.

Young men may entice H. M., but Nathaniel Hawthorne is the novel’s de facto father figure. The story’s most moving moments revolve around the Melville-Hawthorne relationship. A fascinating scene between the two has Hawthorne telling H. M. to think harder about what the white whale in Moby-Dick represents: “Do not restrain yourself.” Hawthorne helps make Moby-Dick what he calls “a great metaphysical romp,” yet Parini does not resolve the enigma of their relationship.

Hawthorne puts up a wall against H. M.’s outward displays of affection, though there are scenes in which H. M. and Hawthorne spend entire evenings in his study at Arrowhead, where they stay up the whole night drinking without (we assume) retiring to their respective beds. Hawthorne’s sudden departure from Berkshire County years later undoubtedly hurts H. M.; later on, en route to his trip to the Holy Land, he meets Hawthorne in Liverpool:

Herman said, “I chose to love you.”

Hawthorne bit his lip. The manner of expression held no appeal for him. It was unmanly, and he would not respond.

Herman shrunk now, letting his head drop. Why did Hawthorne resist him? He tried once again. “You refuse to acknowledge my affections.”

Hawthorne shook his head. “I don’t really think you have the full measure of this.”

While showing a good amount of affection for H. M. and also greatly admiring his writing, Hawthorne continually rebukes H. M.’s advances because he cannot reciprocate H. M.’s feelings. Perhaps because of its contentiousness, the relationship ends rather abruptly; H. M. gauges that “The promise of their friendship had come to nothing, apart from a fleeting sense of sublimity.”

Emphasizing the point in the novel’s title, Parini believes that the source of comfort in Melville’s embattled life was the passage, the solace of movement, from his travels at sea to his long walks through Manhattan. Yet he also lived in passages of the imaginative kind, with the multitude of books he devoured as well as his own philosophizing and poeticizing in his art. At the end of the book, Lizzie says that “He depended on these passages”—taking, absorbing, and creating them. H. M.’s redemption comes once he begins to treat his wife with more affection and sees that his literary reputation will revive. “Herman Melville would live forever,” concludes his wife, who in many ways stood as the ballast to the creator of mad Ahab.

Of course, Parini does his own invaluable part in keeping Melville kicking by combining extensive research from existing biographies with a concrete evocation of the writer’s world and mind. The Passages of H. M. provides imaginative entertainment for those of us who know Melville and his writings, as well as an exciting narrative for those who don’t know enough about one of America’s greatest writers.

======================================================

Ohge on Arrowhead, Melville’s home in the Berkshires

Tagged: Arrowhead, Christoher Ohge, fiction, Herman Melville, Jay Parini, New England