Theater Commentary: American Drama — A Diminished Force

We will not get another Angels in America unless we demand it — and stop accepting bogus substitutes.

Nathan Lane as Roy Cohn and Nathan Stewart-Jarrett as Belize in the London production of Tony Kushner’s “Angels in America.” Photo: Helen Maybanks.

By Bill Marx

Co-lead New York Times theater critics Ben Brantley and Jessie Green, along with three of the paper’s stringers, generated lots of flapdoodle with their list of scripts in “The Great Work Continues: The 25 Best American Plays Since ‘Angels in America.’” But, for me, most of the commentators have ignored the article’s revelation of an acutely embarrassing artistic reality. Since Angels in America we have not had any successful American play (non-musical) that approaches its inspiring size, ambition, imaginative breadth, and political provocation. Why the 25 years of relative modesty? And where are the complaints? Why the pervading sense of smug self-satisfaction among our critics and theater-makers?

In the British online publication The Stage, Andrzej Lukowski (Theater Editor of Time Out London) hints at some possible explanations. He admits that, despite its gridlock of “family reunion” dramas, the NYTimes list has its worthies (including Suzan Lori-Parks’s Topdog/Underdog, Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’s An Octoroon, Wallace Shawn’s The Designated Mourner, and Paula Vogel’s How I Learned to Drive). But he goes on to argue, convincingly, that the contemporary English stage blows the American countdown away. Lukowski mentions, among other dramatists, Caryl Churchill, Lucy Pebble, Alice Birch, Debbie Tucker Green, Martin McDonagh, Mark Ravenhill, Jez Butterworth, and Kwame Kwei-Armah. He doesn’t even note some of the older guns that come to my mind, such as Howard Brenton, Edward Bond, and Peter Barnes. Compared to the finest plays penned by his gathering, ours look small and pat, domestic rather than demonic. Lukowski observes that “outside the top 10, there are few spots of genuine genius: it’s interesting one-hit-wonders and well-crafted middle-class dramas about family reunions.” He doesn’t argue that the best of the Americans aren’t as good as best of the Brits. But we are way outnumbered.

“What should have been a celebration,” Lukowski concludes, “feels instead like a headstone, a presentation of evidence that America is greatly diminished as a dramatic force.” He is spot-on: for two decades the American theater has been content to cower in the shadow of Angels in America. It has gone into retreat, plodding “stolidly away from it.” He laments the situation – “it is bad for all of us” — and hopes that some of the younger playwrights on the NYTimes list will take up the gauntlet. But will they? Lukowski blames the situation on our government’s failure to subsidize the arts. True enough, but there are strong forces, cultural and economic, that are keeping American drama stuck in its strangled nook. We just don’t want what powerful stage drama gives badly enough to make the sacrifices necessary to nurture it.

In America, nothing sucks the oxygen out of the room with more deadly force than financial success. Musicals are booming, so that is where all the attention and money is streaming, a sweet spot that magically unites commerce, branding, and universities. This is not to say there have not been terrific songfests over the past 25 years. Just that it explains why our most talented stage practitioners are not writing plays, but working hard at scoring with the latest lucrative singing/dancing sensation. A number of major repertory theaters, many at educational institutions that should be cultivating serious dramatists, are abdicating their responsibility to develop American plays. Instead, they crank out musicals for export to Broadway. (At the turn of the century, Harvard University assisted the career of Eugene O’Neill. Now, under the artistic entrepreneur Diane Paulus, Harvard’s American Repertory Theater is hopping up The Great White Way with Jagged Little Pill(s).)

The reasons behind the appeal of the musical to the generally white and well-off theater demographic calls for another column. For now, it is enough to point out that music (often of a particularly homogenized kind) makes the medicine/message go down easier, sidestepping what the best plays demand of us: confrontations with the dark, the difficult, the intractable. I came across some apt words by novelist Colum McCann on the duty of imaginative dramatic writing. It should be about “the freedom to articulate yourself against power … You have to stand outside society, beyond coercion, intimidation, cruelty, duress … Become more dangerous … Good sentences have the ability to shock, seduce, and drag us out of our stupor … Transform what has been seen … Oppose the cruelties. Break the silence.” With the rise of social media and the deadly siren call of electronic screens, large and small, theatergoers have become increasingly intolerant of the kind of complex language and thorny ideas necessary to snap them out of their spell. Companies are eager to cater to the demand for spoon-fed comfort, and musicals are a popular vehicle.

The Golden Age of Television is also syphoning off attention, talent, and innovation. Why write a play for the stage when there’s a burgeoning demand for TV scripts that pay well? Granted, the Golden Age of Television has become arguable — we are already beginning to see the downward slide in quality as the demand for more ‘product” is met by an increasingly overcrowded field of producers. But long-form television is where the profitable action is for many of our most talented writers. So American drama has understandably — given the spiraling lack of interest and resources — been bleeding first-class talent for decades. The Australian theater director/playwright Simon Stone put it well: “Jesus Christ, if theatre could be half as good as HBO, we’d be hitting gold.”

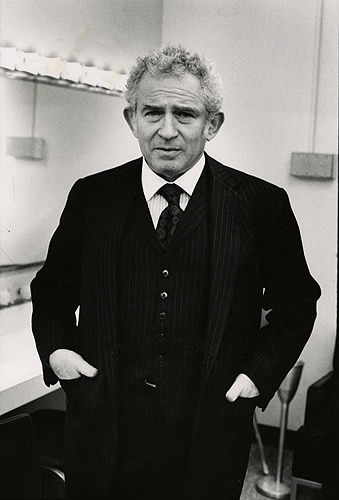

Norman Mailer — no fan of Broadway musicals. Photo: Wiki

Though, of course, television drama is not the answer. It only shapes the increasingly narrow expectations of theatergoers who demand (and then get) what they experience on TV — which undercuts the elemental power of the live stage. Fifty years ago, in “The Playwright as Critic,” Norman Mailer noted TV’s parasitic influence on playwriting as he evaluated some ham-fisted offerings on Broadway (which included the musicals Fiddler on the Roof and Man of La Mancha!). For Mailer, theater, at its best, proffers an experience “sufficiently magical to live in the deepest nerves and most buried caves of the memory … plays [that] speak of the fire at the edge of the wood and hair rising at the back of the neck when the wind becomes too intimate in its sound.” Theater should be “religion for the irreligious.” In contrast, TV “attacks the unconscious like a trip in a jet — you move from continent to continent or spectacle to spectacle without the accompaniment of a change in mood to prepare the flesh. … So a work of deep drama on television would inspire anxiety, for one’s own depths might open to what? — to the baleful electronics of what far-off God? what cold star? No, you keep it neat. The scene is recognizable to ward off any shriek, and the situations are odd and out of focus — just sufficiently unsettling to keep your mind off the flickering of the set.” His vision remains relevant: on what cold star lives Amazon, Netflix, and Facebook?

For Mailer, TV amounts to manipulation, and that sickness has only festered in the theater over the past five decades. (“To talk of Broadway is to talk not of amusement but of disease.”) And that leads to another reason American drama finds itself in such anemic shape. Those who care about the artistic (rather than financial) health of theater are not challenging the growing power of manipulation, aided and abetted by the ethos of business and the passivity of the status quo. Too often, our critics value scripts exactly as the theaters market them. (Boston’s reviewers, for example, are far too Panglossian.) In the short run, that means a dramatic triumph comes along just about every other week. It also encourages dead silence in the face of evidence that there’s a crisis in American drama (as Lukowski suggests), from the scripts picked to be produced to small-bore aesthetic quality and a meagre diversity of voices. For a detailed analysis of why there are so few new scripts with the heft of Angels in America, particularly on our larger, more moneyed stages, please read Todd London’s excellent Outrageous Fortune: The Life and Times of the New American Play.

Salesmanship fades after twenty-five years, and a demeaning reality can be glimpsed through the mountains of confetti. The truth is, superior drama demands a genuinely radical/mad imagination, one that goes beyond sound bites, that doesn’t worry about placating the tastes of aging white audiences. We need audacity, not mechanical bows at the cardboard altar of ’empathy.’ We will not get another Angels in America unless we demand it — and stop accepting bogus substitutes.

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of The Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

I saw Angels In America in New York on May 23 a day will not forget.

This is the great American play of the second half of the 20th century.

You only have thru July 15,see both parts on the same day

There are so many dubious comments in this piece, it’s hard to know where to start.

The false equivalency of George Pierce Baker and Diane Paulus is a beginning. Aside from both having a connection to Harvard, they are not remotely comparable. By the way, Baker moved to Yale because Harvard didn’t take him seriously. He founded what became the Yale Drama School, which was revitalized by Robert Brustein, who began the Yale Rep which helped launch August Wilson’s career.The Rep has continued to premiere important new plays by significant writers. Brustein, after leaving Yale, founded ART, which does considerably more than produce musicals. Marx is cherry-picking, as anybody conversant with serious theater knows.

The condescension about musicals is snobbery, by the way. I don’t give a rat’s ass if Mailer didn’t like FIDDLER ON THE ROOF. He never wrote a dramatic work that was worth a tenth of FIDDLER. He wrote some swell stuff, but what he knew about the theatre was minimal.

The TIMES piece is NOT the index of the health of the American theatre. It is a list of plays that a handful of TIMES critics saw, mostly in New York. They missed a lot of good stuff both in New York and around the country, so their list represents little but their own narrow view of the scene. (It also missed some very strong plays that they underappreciated, including two fine plays by Rinne Groff that I would not have hesitated to put on the list.)

There may well be dubious statements (it is an argument, after all), but you don’t point out any. I don’t set up an equivalence between Diane Paulus and George Pierce Baker. What I do assert is that, unlike Baker and Brustein, Paulus is primarily dedicated at the A.R.T. to creating boffo musicals that are tailor-made to go to Broadway. She is not into nurturing straight plays. And that is a significant change in the mission of what is considered a major repertory theater.

I don’t argue that musicals can’t be good. I am talking about the diminished state of straight plays in the American theater. The idea that a critic, like Norman Mailer, can’t make a valid point about the stage without having created a successful theater work is an adolescent canard. I use Mailer to point out that theater should have greater significance than being entertainment or being ‘good.’ (And that there is value in the perceptions of an ‘outsider.’) As for being called a ‘snob,’ that almost becomes a badge of honor in our current monoculture, in which everything is as good as anything else. Whatever floats your boat … it’s art.

Meanwhile, note that Sweet leaves my major argument untouched — perhaps because he knows I am right. Nobody would assert that there have not been ‘good’ plays since Angels in America. I don’t, and neither does the Time Out London Theater Editor. But few dramatists (or producing theaters) have come along that take a crack at equaling its range, political bite, and ambition. Why not? Why didn’t that drama spark the production of other scripts of its caliber? The limitations of the NYTimes list are obvious (alas, the NYTimes exerts an unhealthy influence on the scripts a large number of theaters around the country choose to stage, including in Boston). But the round-up clarifies a weakness in contemporary American playwriting. It’s smallness. And that fact should be acknowledged, rather than ignored.

You wrote: “(At the turn of the century, Harvard University assisted the career of Eugene O’Neill. Now, under the artistic entrepreneur Diane Paulus, Harvard’s American Repertory Theater is hopping up The Great White Way with Jagged Little Pill(s).)” The juxtaposition of these two items is meant to suggest the decline of Harvard’s commitment to serious theatre, which certainly implies that you think it is appropriate to compare them. The phenomenon of O’Neill having been a part-time student at Harvard a century ago (taught by a professor who felt so unsupported by Harvard that he left) has little to do with Paulus except they may have walked some of the same streets. And what Paulus has been producing (which is more varied and ambitious than you suggest) has little to do with the general pattern of what is being done at the very varied schedules of the non-profits, large and small, across the country. One non-profit does not represent all. Some are lively and adventurous and producing new stuff, and some are museum theatres, giving their communities access to classics they would not otherwise encounter. (And some do both.) Some companies do indeed include tryout engagements of musicals as part of their seasons. But that is hardly all they do. Indeed, it is a small minority of what they do. (By the way, the O’Neill scholars don’t claim that he wrote anything worth much in Baker’s class. O’Neill himself, in writing a tribute to Baker for a ceremony at Yale, stopped short of saying that Baker taught him anything. He wrote that Baker’s value to him was taking him seriously.)

Mailer? He was talking about a Broadway theater more than a half century ago and about television that bears little relationship to what is being done today. He was often prone to grand pronouncements based on scant experience. He loved be viewed as an authority even in areas where he had little basis for that claim. (It’s not for nothing he called one book ADVERTISEMENT FOR MYSELF.) And yes, his understanding of the theatre and what it lacked informed his attempts at writing for the stage and those attempts were of little consequence. But you think his comments, based largely on his dismissal of musicals of the day, has something useful to offer to a discussion about work being done today? I don’t share your opinion. “I use Mailer to point out that theater should have greater significance than being entertainment or being ‘good.’ ” Please point out what in what I wrote that suggests I think that theater shouldn’t have greater significance than being entertainment or being “good.” You are refuting a claim I have not made. And something so self-evident hardly needs the support of Mailer’s huffing and puffing.

You have the sliver of a valid point in that much of American playwriting is built on a smaller scale than the best of what we see from Britain. (We don’t see much of the run-of-the-mill stuff in Britain, of which there is plenty, because only the well-reviewed stuff is brought over or shown via NTLive or Digital Theatre online.) The National Theatre and the RSC have the budgets to commission and produce big plays embracing grand themes that not many American companies have, and American writers tend to write to accommodate the stages available to them, which tends to mean smaller-cast plays.

You write, “But few dramatists (or producing theaters) have come along that take a crack at equaling [ANGELS’] range, political bite, and ambition.” But there are indeed more than a few companies and writers in the States attempting works of scale. Lincoln Center has made a habit of putting up large-scale attempts. Sometimes they work (OSLO) and sometime they don’t (JUNK), but the effort is worth noticing. (OSLO ended up playing successfully at the National, where I gather it looked very much at home.) The Ashland Festival in Oregon has been commissioning a series of plays — many of them quite large and ambitious — dealing with historical/political themes. Robert Schenkkan’s LBJ plays started there and have been enthusiastically received, and Lynn Nottage’s SWEAT began its journey to the Pulitzer there. Even the ones that don’t quite work there are ambitious (such as PARTY PEOPLE, an account of the early days of the Black Panthers). The Public Theatre’s production of THE LOW ROAD by Bruce Norris was an epic take-down of American capitalism viewed from colonial days, mixing CANDIDE with a hint of Shaw. Rajiv Joseph’s DESCRIBE THE NIGHT (at the Atlantic) was another epic, covering almost a century of the dark corners of Soviet history. Nothing small about that. In Chicago at the Goodman, Robert Falls put up a five-hour piece called 2666 which was nothing if not ambitious. How many of these did you get to see?

There are some general differences between British and American writing. Americans seem to be at their best writing about family and race, and the Brits focus more on history and class (though you could come up with counter-examples on both sides of the Atlantic pretty easily). The biggest difference between us is that Americans know how to write adventurous musicals and the Brits rarely come up with a good one. But you don’t want to talk about musicals.

I repeat: the TIMES roundup strikes me as revealing a weakness not so much in contemporary American playwriting talent as a narrowness in the range of what the TIMES critics cover and appreciate. (I note the irony that David Henry Hwang’s YELLOW FACE, which ranks high on their list, was in fact back-handed by the TIMES when it opened.) And their coverage is shrinking. Indeed, as you well know, arts coverage in general is shrinking, which is why, though I disagree with you now and again, I am pleased that THE ARTS FUSE is trying to do something about it.

I will not back down from my assertion that under Baker and Brustein Harvard University/A.R.T. was more committed to serious theater than it is today. (Your quotation from O’Neill makes my point.) The de-evolution is a reality. I believe that looking back at the history of an institution and its treatment of theater is a valid exercise, and that Paulus represents a reversal regarding the commitment of the company to nurturing plays rather than musicals. In truth, she is more of an entrepreneur than an artist — she generally packages musical productions.

I did not say that one non-profit theater represents all — but what a major regional company does impacts others, in the same way that when the NYTimes cuts back on its arts coverage it gives permission to others, such as the Boston Globe, to limit its commitment to writing on culture. I am talking about artistic trends here: substantial theater companies that should be producing serious plays are concocting more and more musicals. There is a revealing political component to this state of affairs: a piece could be written about how the manipulative populism of musicals (Disney-branded, etc) dovetails with the populism of Trump.

Thank God for gadflies like Mailer. Broadway is a disease? How can he say that? We need more of these wisenheimers today, rather than those who are far too eager to support the status quo. For some entrenched interests, the party must never end. My interest in the Mailer piece is that he nailed, fifty years ago, how Broadway was all about manipulation. It still is today, mostly. Musicals were only part of what he was lambasting: there were some words of praise for Harold Pinter’s The Homecoming and William Alfred’s Hogan’s Goat. You should read the piece. It will get your heart pumping.

You provide a list of theater ‘epics’ (doubtfully Brechian), and I am glad you are excited about them. But unlike Angels, they have made little cultural impact and generated little controversy. At least given what I have read about them. Most have not been produced in Boston, at least not yet. Let’s see if companies here think there is a pressing need to view these giants. (Reality check: it would really help their staging chances if the NYTimes raved about them.) Of the ones I have seen I would not accept your cheery characterization — Robert Schenkkan’s LBJ plays are amiable re-dos of PBS documentaries. Who would be challenged by them? I read The Low Road and, while it is entertaining in a Tom Jones sort of way, there is precious little sting — Adam Smith gets off way easy. My quick, admittedly sloppy, generalization is that the main topics of American plays, “family and race” are not handled in a way that challenges the liberal consensus championed by white funders and audiences. And that some issues, such as class, unions, and Climate Change, are too dangerous to be touched. In other words, you can look big but be small at the same time. America — both on the left and right — is quite good at that trick.

I don’t talk about musicals because that is not the mission of the column, which is to sound the alarm about the diminishing power of plays. Musicals are getting bigger and bigger, garnering more and more attention and — for the successful examples — bringing in bigly profits. Many write about this state of affairs with pride and joy. (Again, I suggest people read Todd London’s excellent Outrageous Fortune for a detailed analysis of why significant new plays are struggling to be born while musicals are thriving.) I and a few others dissent (dare I say Resist?). Which is what criticism should be about and why The Arts Fuse is around.

The real issue is that plays today support the liberal-left status quo. They do not challenge it one bit. Theater in America cannot be, and won’t be “politically incorrect.” Who would produce such a play? Who would see it? Playwrights preach to the choir and are happy to do so. It’s what pays. They are nothing more than flacks and propagandists for the dominant liberal-left, secular humanist narrative.

I go to the theater a lot in the Bay Area and I’ve just become inured to it. The only respite is Pinter, when they do one of his plays. Otherwise, it’ all like a liberal church piece.

I think this piece touches on the problem, and the replies move closer to it, but this is the source of the problem. Rather than attacking and questioning the dominant cultural narrative, our theater shores it up and supports it. This isn’t art and it can’t be art. But to move beyond these confines? That take courage the producers and consumers do not have and do not want.

I want to broaden your idea. There are places where liberal-left and conservative-right comfortably meet, such as an appetite for optimism rather than tragedy, for the changeable rather than the intractable, for the denial of realities that call for sacrifice (in terms of dealing with Climate Change, issues of class and poverty, for example), for the value of consumption, even while condemning it. That is where playwrights should go, if theaters had the courage to let them. My idea of rebellion against the status quo is not as one-note and neat as having dramatists challenge one end of the ideological spectrum. That leaves us in the same predicable situation.

And we desperately need to hear from dramatic voices outside of the usual academic/theater incorporated channels. The latter, orientated toward commercial success, seem to be dedicated to homogenizing the dramatic imagination, training writers to produce material that will fit into the current safe molds. Designing the egg to fit the chicken.

I think this answer may be seeking a kind of compromise which opposes the shock you are looking for. I started working on a play in which a wealthy Jewish family in New York, very left-liberal, had to confront their past involvement with murderous communism. You think anyone would produce that exploration into guilt and repressed memory? Does anyone in the American theater community want to see THAT group suffering?

How about a play that exposes the lies that the middle class African American community tells itself? Plays in which white liberals are forced to confront their hypocrisy are common. Why don’t black people, Jews, and Asians get that chance? Is that fair? To deprive them of that visceral catharsis?

What kind of play would be shut down by the police or local government? You want that level of transgression, but our artists… are they on the other side of the power equation now?

I wasn’t asking for anything that the police would shut down or anything hair-raisingly shocking. I have no problem with dramas based on the story ideas you mention — it is all in the execution. A play about Climate Change — and the reassuring liberal/conservative illusion that ‘sustainability’ will be enough — wouldn’t be all that radical. It might be upsetting … and provocative.

And what’s wrong with that? In Medea, Euripides wrote a play in which a woman kills her children and is whisked away from justice by the gods. Tragedy? Comedy? Both?

Great art arises out of friction, as a friend noted. In a society that seeks to reduce friction – through therapy, drugs, and indoctrination – how can artists experience the friction that art needs? Tony Kushner grew up gay in Louisiana. Who is is going to have similar problems now?

Our audiences seem to desire, more than anything else, that their values and beliefs be RATIFIED by the theater, not questioned and challenged by it. I think the people making plays suffer from the same need to offer self-congratulating fare. When the ruling class looked like it did in the 1950s and 1960s, theater arrived to combat it. Now that the ruling class looks the way it does – running the cultural institutions – who wants to fight it?

We also need to have ways of looking at art that go beyond evaluations of how “diverse” the cast is and how well or not it conforms to standard PC agendas. But I don’t see a rising, younger generation who knows how to do that.

Conflict is key — we are currently a society filled with friction, generated by one side or another for its short term interests. To me, just making the requirement an anti-PC response is narrow. There are unquestioned beliefs that the PC and un-PC crowd share. That is where some fertile ground for powerful theater lies. And there are other directions that go beyond the very, very tired PC versus un-PC see-saw. The latter is the basis for bickering on talk shows and Cable TV news programs, not powerful drama.

How much do you yourself feel comfortable challenging the PC taboos? You’re right, right wing theater that glorifies a white-bread 1950s past is going to be deathly dull. We’re not looking for theater from the simplistic white Evangelical church either.

But you’re still dodging the crucial issues. Look at ”Clybourne Park.” Why didn’t that play reveal why the neighborhood the house was in fell apart? Sure, the white people in this play are all clowns. Why aren’t the African Americans also having their own weaknesses and contradictions revealed? Is that just a “conservative” reaction – to reveal that particular community’s OWN hypocrisies and conflicts and contradictions? I don’t think it is. But to challenge the prevailing way of treating African Americans in theater one has to risk running up against PC taboos while not, at the same time, endorsing the standard “conservative” position.

In the same way, you can make a play about Jewish hypocrisy that is not, necessarily, conventionally antisemitic. But the playwright and the company MUST run the RISK of being called that. Who would fund that play and work on it?

The values of today’s PC liberal theater are just as boring and as stultifying as pre-1950s theater ever was. You want to challenge that? You have to take real risks. Who is ready to do that?

I am a critic, not a playwright. But I feel completely comfortable challenging PC cliches (conservative and liberal) when warranted in my criticism. One of the values of being a small, independent arts magazine is that reviewers are encouraged to say what they think — as long as it is reasoned, intelligent, stylish, etc. Over the decades I have been called everything in the book by companies I have reviewed — homophobic, anti-feminist, radical anti-conservative, agist, size-ist, etc. What kind of critic can’t stand being disagreed with? Serious discussion means you are taking the theater seriously — when reviewers see it as their duty to churn out blurbs that means criticism has become publicity.

As I said before, substantial conflicts — issues of justice, power, responsibility, class, climate change, hubris, etc. — cut all ways. That is what I want to see as a drama critic — that is not what I am getting on stage, at least not often. Critics should call out the faux — and support the real thing. When I see the latter, I do what I can to get the word out. Who will stage that kind of work? Most of the time, theater companies and playwrights on the margins, not part of the musical-crazed mainstream. Don’t expect to become rich and successful if you are biting (rather than shaking) the hand of the status quo.

Came across this line in a 1985 interview with one of my favorite living poets, Abdellatif Laâbi. “I accept the term ‘engaged’ poetry … when it … pursues its adventure to the end, and does not fear being called to account or being subjected to burning interrogations.” Exchange the word poetry with theater and it sums up what I am arguing for.

Look, we’ve managed to produce exactly ONE giant playwright and that was O’Neill. After him it’s all one-hit wonders–by which I’m referring not to FINANCIAL, but AESTHETIC success. I’m sorry, but I’m hard-pressed to care about more than one fine-to-great play from the likes of:

David Mamet (American Buffalo)

Tennessee Williams (Eccentricities of a Nightingale)

Lorraine Hansberry (Raisin in the Sun)

Charles Johnson (A Soldier’s Tale)

Tony Kushner (Angels in America)

The remainder of the output of the above all come under the heading of “okay dramas mistakenly taken for timeless ones” and are (or will be) correctly forgotten by history while typically having absolutely NO legs outside this country–which should tell one something. It does me.

Arthur Miller, unfortunately doesn’t even make THAT list, I’m afraid, though Salesman is, of course, produced all over the world. While hitting many notes a certain sort of mindset finds satisfying in ideological terms, the play’s banal language, cookie-cutter structure (see his professor Kenneth Thorpe Rowe’s instructional manual on how to write plays), and obvious attempt render economics as drama relegate it to assembly line play writing.

Face it, the cinema sucked the talent base away from the theater, along with the pressure to conform to left-of-center demands regarding what they will permit to be said or expressed in the court of public opinion (to which the arts, of course, contribute) and the American drama has never recovered. Our cinema is the envy of the planet, but the English language theater refers to the English stage, not ours. Again, Eugene O’Neill excepted.